Summer, the Year 2100

It was decided. We would make a family holiday of it. All of us, even my sister, were going to see the big guns of Kugluktuk. I could hardly contain my excitement as the school holidays slowly approached. Each long day, sitting in class, I wiled away my time, fidgeting through math and sleeping through physics. I mean, what was a boy to do when the big guns beckoned.

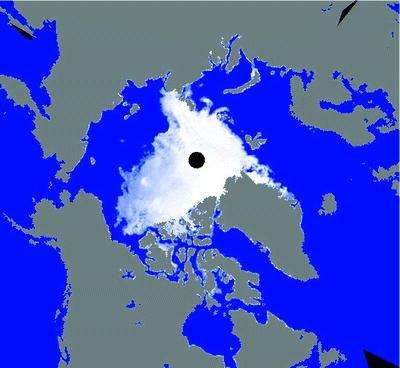

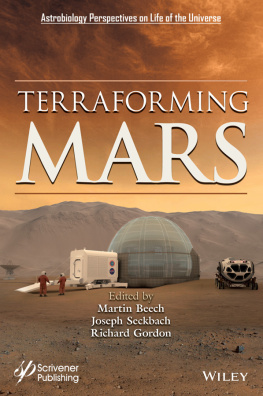

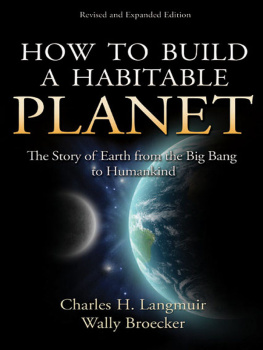

Figure 1.1.

Satellite view of the Arctic ice coverage. On 15 August 2007, the area covered by the Arctic ice sheet reached its lowest ever recorded value of 5.31 million square kilometers. The thinning and reduction in size of the Arctic ice fields has been accelerating over recent decades as a consequence of global warming. It is predicted that by 2100 there may be no Arctic ice at all. Image courtesy of the Japanese Space Agency.

Time crawled by. It seemed an eternity, but the day eventually arrived when my father, after one final look around the house for any missed luggage, locked the front door and climbed into the family car. I had somehow managed to convince everyone that I should be the front-seat passenger (normally a much sought-after, and fought-over, seat), and even though we didnt need it I had the route map open in front of me. Head north and drive for 6 days straight; that was our route.

We crossed the prairies of Saskatchewan, through the boreal forest, and over the fly-blown taiga and muskeg. The northern highway was in excellent condition, and we made steady progress. There was so much to see, and I didnt even mind the stopovers at night or the quick museum and wildlife reserve visits during the day. The point was we were heading north, and our destination was getting closer.

The final few days of travel became long and hot, but as we neared the city of Kugluktuk my sense of anticipation became fever pitch. Well soon be there, well soon be there, I kept repeating to myself, and there will be a whole day to spare before the shelling begins.

Kugluktuk is the Inuit name for the old town of Coppermine. Situated on the northern Canadian coast, it had become a much sought-out tourist destination. The region boasted of long, hot summers and endless beaches, rolling seas, and gentle ocean breeze. The prosperity of Nunavut, and Kugluktuk in particular, had come about because of global warming and the opening up, all year round, of the Northwest Passage to shipping. The Arctic ice had long ago vanished from the northern seas, and one can even take a boat trip to the North Pole these days. The whole area was undergoing an economic boom; vast oil and natural gas reserves had been discovered under the seafloor, and extraction platforms of one kind or another dotted the entire panorama.1

Although global warming had brought prosperity to northern Canada, the regions to the south were doing less well. The climate there had become so hot and fresh water so scarce that what used to be the breadbasket of the world was now mostly desert and useless scrubland. In an attempt to address the global warming problem and to cool the Earth down, the United Nations had begun to fund and organize a vast network of giant cannons, their purpose being to fire and then explode massive sulfur dioxide-bearing shells into Earths upper stratosphere.2

Welcome to the Baltimore Gun Club read the sign above the big gun interpretive center. This was apparently a reference to a book written two and half centuries ago by an obscure French writer called Jules Verne. I made it my intention to find a copy of the book when I returned home. One of the introductory displays at the center explained that the idea of firing sulfur pellets into the stratosphere was to mimic the cooling effects caused by volcano plumes. This phenomenon was first noticed and investigated in the late twentieth centurythe good old days. Nobel Prize-winning chemist Paul Crutzen made some of the first detailed model predictions in 2006 and found that a thin layer of stratospheric sulfur dioxide could counterbalance the warming trend due to the ever-increasing abundance of greenhouse gases.3 The sulfur dioxide layer had the effect of increasing the Earths albedo, thereby reflecting back into space more of the incoming sunlight.

Well, of course, the rest is history. Governments around the world bickered about greenhouse gas reduction quotas, and nothing useful was actually done to stop global warming. Apparently, and I thought this was well-worth knowing for Trivial Pursuits games, the derogatory expression Thats a load of Kyoto was coined during the early 2020s. It was also at about this time that the science of geoengineering came into its own, and, of course, it is now one of the most profitable industries on the Earth. But enough history!

The guns were due to start firing at 13:00 hours, and I wanted a grandstand seat. Ever since I can remember, the Kugluktuk guns had been fired every 4 years, and this time I was going to see the show.

A total of 100,000 tons of sulfur was going to be placed into the stratosphere. The 200 mighty guns of the Kugluktuk range were going to fire, one after the other, again and again, a withering barrage of 50,000, two-metric ton sulfur-laden shells straight upward. Each cannon would fire 250 shells over a 48-hour periodabout one shell per cannon every 12 min. It was going to be an incredible show. We were seated in the grandstand arena some 25 km away from the nearest vertical barrel. Each gun was spaced 2 km apart, and we were located opposite gun 100, half way down the chain. I could see the muzzle flashes long before the ground and grandstand began to shake to the thunderous timpani of the discharges. The sound was tumultuous; it blasted us mercilessly, and we loved it! The guns fired and fired. The flash from each barrel shot like a billowing flame, all yellow and gold into the sky. In clockwork fashion, one after the other, each cannon would discharge its massive shell that would sedately climb into the azure heavens. After each discharge, the muzzle plumes would darken into a mustard-brown cloud that twisted and gamboled like some demented draco volans as it drifted downrange.

Again and again the great guns fired. I sat there for hour after hour, the power of the percussion overwhelming my senses. My body shook, my ears felt as if they would burst, and my eyes began to hurt as they took in the shock of each new muzzle flash. The sensations were better than any carnival ride, and I had the time of my life: the scene was both terrifying and awe inspiring. The big guns of Kugluktuk were rocking the skies and cooling the planet Earth.