1.1 First Light

It was a clear and windless winters evening in early July when this author first saw Centauri. Brought into sharp focus by a telescope at the Stardome Observatory Planetarium in Auckland, New Zealand, its light was of a cold-silver. The image was crisp and clear, a hard diamond against the coal-black sky. The view was both thrilling and surprising. To the eye Centauri appears as a single star the brightest of the pointers. Indeed, to the eye it is the third brightest star in the entire sky, being outshone only by Sirius and Canopus (see Appendix 1).

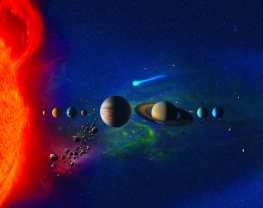

Through even a low-power telescope, however, a remarkable transformation takes place, and Centauri splits into two: it is a binary system. Composed of two Sun-like stars, Cen A and Cen B orbit their common center once every 80 years, coming as close as 11.3 AU at periastron, while stretching to some 35.7 au apart at their greatest separation (apastron). Perhaps once in a human lifetime the two stars of Centauri complete their rounds, and they have dutifully done so for the past six billion years (as we shall see later on). Having now completed some 75 million orbits around each other, the two stars formed and began their celestial dance more than a billion years before our Sun and Solar System even existed. The entire compass of human history to date has occupied a mere 125 revolutions of Cen B about Cen A in the sky, and yet their journey and outlook is still far from complete. Indeed, the Centauri system will outlive life on Earth and the eventual heat-death demise of the planets within the inner Solar System.

However, a hidden treasure attends the twin jewels of Centauri. A third star, Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun at the present epoch, lurks unidentified in the background star field. Proxima is altogether a different star from either Cen A or Cen B. It is very much fainter, smaller in size and much less massive than its two companions, and it is because of these diminutive properties that we cannot see it with the unaided eye. These are also the reasons why it will survive, as a bona fide star, for another five trillion years. Not only will Proxima outlive humanity, the Sun and our Solar System, it will also bear witness to a changing galaxy and observable universe.

For all this future yet to be realized, however, the story of Proxima as written by human hands begins barely a century ago, starting with its discovery by Robert Innes in 1915 at a time when civilization was tearing itself apart during the first Great War.

However, we are now getting well ahead of ourselves. Let us backtrack from the present-day and see what our ancestors made of the single naked-eye star now called Centauri.

1.2 In Honor of Chiron

The constellation of Centaurus is one of the originals. It has looked down upon Earth since the very first moments of recorded astronomical history. It is the ninth largest, with respect to area in the sky, of the 88 officially recognized constellations, and it was described in some detail by Claudius Ptolemy in his great astronomical compendium written in the second century A.D. Ptolemy placed 37 stars within the body of Centaurus, but modern catalogs indicate that there are 281 stars visible to the naked eye within its designated boundary (Fig. ). The two brightest stars, and Centauri, however, far outshine their companions, and they direct the eye, like a pointillist arrow, to the diminutive but iconic constellation of Crux the Southern Cross.

Fig. 1.1

The constellation of Centaurus (Image courtesy of the IAU and Sky & Telescope, Roger Sinnott and Rick Fienberg, Centaurus_IAU.svg)

In order to ease the discussion that is to follow let us, with due reverence, refine and reduce the skillfully crafted map of Fig.. Even without our pairing down, an abstract artists eye is required to unravel the hybrid body being traced out, point by point, by the stars in Centaurus. This twisted perception is perhaps even more compounded by the fact that the centaur, so revealed by the stars, is a mythical beast, created entirely by the human imagination rather than the level-headed workings of natural selection and evolution. The half-man, half-horse centaurs take us back to a time in history that was ancient even to the ancient Greeks; to a time when capricious gods were thought to play out their political games, jealousies and in-fighting on Earth. The centaur, in literature at least, has typically been thought of as being fierce, when and if the need arises, but generally learned and wise. C. S. Lewis in his Chronicles of Narnia portrays them as noble creatures that are slow to anger but dangerous when inflamed by injustice. J. K. Rowling, in her Harry Potter series of books, places the centaurs in the Forbidden Forrest close by Hogwarts, making them both secretive and cautious. For all this, however, they are taken as being wise and skilled in archery.

Fig. 1.2

A minimalist star map for Centaurus. The ten stars depicted are all brighter than magnitude +3.2 and easily visible to the naked eye. The radiant location for the Centaurid meteor shower, at about the time of its maximum activity, is shown by the * symbol

Chiron is generally taken to have been the wisest of centaurs, and it is Chiron that, in at least some interpretations of mythology, is immortalized within the stars of Centaurus. His story is a tragic one. The Roman poet Ovid explains in his Fasti (The Festivals, written circa A.D. 8) that Chiron was the immortal (and forbidden) offspring of the Titan King Cronus and the sea nymph Philyra. Following a troubled youth Chiron eventually settled at Mount Pelion in central Greece and became a renowned teacher of medicine, music and hunting.

It was while teaching Heracles that Chirons tragic end came about. Being accidentally shot in the foot with an arrow that had been dipped in Hydras blood, Chiron suffered a deathly wound, but being immortal could not die. For all his medical skills Chiron was doomed to live in pain in perpetuity. Eventually, however, the great god Zeus took pity on the suffering centaur, and while allowing him a physical death he preserved Chirons immortality by placing his body among the stars. It is the brightest star in Centaurus that symbolically depicts the wounded left hoof of Chiron.

In the wonderful reverse sense of reality aping mythology the flight of Chirons death-bringing arrow is reenacted each year by the Centaurid meteor shower. Active from late-January to mid-February the Centaurid shooting stars appear to radiate away from Chirons poisoned hoof (see Fig. ). Bright and swift, the Centaurid meteors are rarely abundant in numbers, typically producing at maximum no more than 10 shooting stars per hour. In 1980, however, the shower was observed to undergo a dramatic outburst of activity. A flurry of meteors were observed on the night of February 7, with the hourly rate at maximum rising to some 100 meteors, a high ten times greater than the normal hourly rate. The small grain-sized meteoroids responsible for producing the Centaurid meteors were released into space through the outgassing of a cometary nucleus as it approached and then rounded the Sun, but the orbit and identity of the parent comet is unknown. It is not presently known when or indeed if the Centaurid meteor shower will undergo another such outburst. Only time, luck and circumstance will unravel the workings of this symbolic, albeit entirely natural, annihilation re-enactment.