Factoring Humanity

by Robert J. Sawyer

What is mind? No matter.

What is matter? Never mind.

Thomas Hewitt Key (17991875) British classicist

The messages from space had been arriving for almost ten years now. Reception of a new page of data began every thirty hours and fifty-one minutesan interval presumed to be the length of the day on the Senders homeworld. To date, 2,841 messages had been collected.

Earth had never replied to any of the transmissions. The Declaration of Principles Concerning Activities Following the Detection of Extraterrestrial Intelligence, adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1989, stated: No response to a signal or other evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence should be sent until appropriate international consultations have taken place. With a hundred and fifty-seven countries comprising the United Nations, that process was still going on.

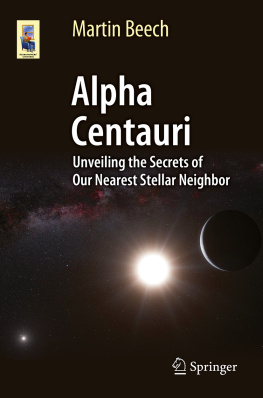

There was no doubt about the direction the signals were coming from: right ascension 14 degrees, 39 minutes, 36 seconds; declination minus 60 degrees, 50.0 minutes. And parallactic studies revealed the distance: 1.34 parsecs from Earth. The aliens sending the messages apparently lived on a planet orbiting the star Alpha Centauri A, the nearest bright star to our sun.

The first eleven pages of data had been easily deciphered: they were simple graphical representations of mathematical and physical principles, plus the chemical formulas for two seemingly benign substances.

But although the messages were public knowledge, no one anywhere had been able to make sense of the subsequent decoded images

Heather Davis took a sip of her coffee and looked at the brass clock on the mantelpiece. Her nineteen-year-old daughter Rebecca had said shed be here by 8:00 P.M., and it was already eight-twenty.

Surely Becky knew how awkward this was. She had said shed wanted a meeting with her parentsboth of them, simultaneously. That Heather Davis and Kyle Graves had been separated for almost a year now didnt enter into the equation. They could have met at a restaurant, but no, Heather had volunteered the housethe one in which she and Kyle had raised Becky and her older sister Mary, the one Kyle had moved out of last August. Now, though, with the silence between her and Kyle having stretched on for yet another minute, she was regretting that spontaneous offer.

Although Heather hadnt seen Becky for almost four months, she had a hunch about what Becky wanted to say. When they spoke over the phone, Becky often talked about her boyfriend Zack. No doubt she was about to announce an engagement.

Of course, Heather wished her daughter would wait a few more years. But then again, it wasnt as if she was going to university. Becky worked in a clothing store on Spadina. Both Heather and Kyle taught at the University of Torontoshe in psychology, he in computer science. It pained them that Becky wasnt pursuing higher education. In fact, under the Faculty Association agreement, their children were entitled to free tuition at U of T. At least Mary had taken advantage of that for one year before

No.

No, this was a time of celebration. Becky was getting married! That was what mattered today.

She wondered how Zack had proposedor whether it had been Becky who had popped the question. Heather remembered vividly what Kyle had said to her when hed proposed, twenty-one years ago, back in 1996. Hed taken her hand, held it tightly, and said, I love you, and I want to spend the rest of my life getting to know you.

Heather was sitting in an overstuffed easy chair; Kyle was sitting on the matching couch. Hed brought his datapad with him and was reading something on it. Knowing Kyle, it was probably a spy novel; the one good thing for him about the rise of Iran to superpower status had been the revitalization of the espionage thriller.

On the beige wall behind Kyle was a framed photoprint that belonged to Heather. It was made up of an apparently random pattern of tiny black-and-white squaresa representation of one of the alien radio messages.

Becky had moved out nine months ago, shortly after shed finished high school. Heather had hoped Becky might stay at home a whilethe only other person in the big, empty suburban house now that Mary and Kyle were gone.

At first, Becky came by the house frequentlyand according to Kyle, she had seen her father often enough, too. But soon the gaps between visits grew longer and longerand then she stopped coming altogether.

Kyle apparently had become aware that Heather was looking at him. He lifted his eyes from the datapad and managed a wan smile. Dont worry, hon. Im sure shell be here.

Hon. They hadnt lived together as husband and wife for eleven months, but the automatic endearments of two decades die hard.

Finally, at a little past eight-thirty, the doorbell rang. Heather and Kyle exchanged glances. Beckys thumbprint still operated the lock, of courseas, for that matter, did Kyles. No one else could possibly be dropping by this late; it had to be Becky. Heather sighed. That Becky didnt simply let herself in underscored Heathers fears: her daughter no longer considered this house to be her home.

Heather got up and crossed the living room. She was wearing a dresshardly her normal at-home attire, but shed wanted to show Becky that her coming by was a special occasion. And as Heather passed the mirror in the front hall and caught sight of the blue floral print of the dress, she realized that she, too, was acting as Becky was, treating her daughters arrival as a visit from someone for whom airs had to be put on.

Heather completed the journey to the door, touched her hands to her dark hair to make sure it was still properly positioned, then turned the knob.

Becky stood on the step. She had a narrow face, high cheekbones, brown eyes, and brunette hair that brushed her shoulders. Beside her was her boyfriend Zack, all gangly limbs and scraggly blond hair.

Hello, darling, said Heather to her daughter, and then, smiling at the young man, whom she hardly knew: Hello, Zack.

Becky stepped inside. Heather thought perhaps her daughter would stop long enough to kiss her, but she didnt. Zack followed Becky into the hall, and the three of them made their way up into the living room, where Kyle was still sitting on the couch.

Hi, Pumpkin, said Kyle, looking up. Hi, Zack.

His daughter didnt even glance at him. Her hand found Zacks, and they intertwined fingers.

Heather sat down in the easy chair and motioned for Becky and Zack to sit as well. There wasnt enough room on the couch next to Kyle for both of them. Becky found another chair, and Zack stood behind her, a hand on her left shoulder.

Its so good to see you, dear, said Heather. She opened her mouth again, realized that what was about to come out was a comment on how long it had been, and closed it before the words got free.

Becky turned to look at Zack. Her lower lip was trembling. Whats wrong, dear? asked Heather, shocked. If not an engagement announcement, then what? Could Becky be ill? In trouble with the police? She saw Kyle lean slightly forward; he, too, was detecting his daughters anxiety.

Go ahead, said Zack to Becky; he whispered it, but the room was quiet enough that Heather could make it out.

Becky was silent for a few moments longer. She closed her eyes, then re-opened them. Why? she said, her voice quavering.

Why what, dear? said Heather.

Not you, said Becky. Her gaze fell for an instant on her father, then it dropped to the floor. Him.

Why what? asked Kyle, sounding as confused as Heather felt.

The clock on the mantelpiece chimed; it did that every quarter-hour.

Why, said Becky, raising her eyes again to look at her father, did you