Table of Contents

AUTHORS NOTE

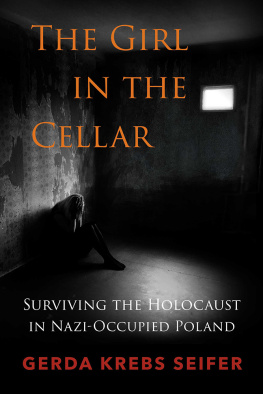

The story of Mania Fishel Kroll is true. Because Mania was a child when her family was torn apart following the German invasion of Poland in the fall of 1939, a few of her memories are hazy and some are fragmentary. On the few occasions when this was the case, and the memories were not of historic importance, I took the liberty of fleshing out the social and domestic details based on the norms at that time in Poland. However, all the essential facts of Manias life, such as being driven from her home, rounded up with her family in the Sosnowitz Athletic Field Aktion, and placed in a ghetto, and then in Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp before being sent to a slave labor camp, have been verified by documentation in Polish university and government archives.

It has not been possible to verify all the facts of Johanne Mllers life, nor the credibility of all she told me. Allied bombing raids, land warfare, and the actions of German authorities towards the wars end destroyed much official documentation. Administrators of concentration and slave labor camps were particularly successful in erasing all files relating both to personnel and prisoners. The files at Auschwitz-Birkenau were preserved only because of the secret work done by prisoners who were members of the resistance. Nonetheless, it has been possible to establish certain facts of Johannes life. When detailsperipheral and inessential to these factswere missing but desirable either for readability or a better understanding of Johannes actions, I drew conclusions from intimations and hints given by Johanne, sometimes with pride, sometimes unwittingly.

This book draws on my own longtime interest in the history of the Second World War as well as the extensive research done by Vancouver documentary filmmaker Maureen Kelleher. Without Maureens tenacious work in Germany and Poland and her generosity in sharing her findings, this book would never have been written.

PREFACE

The story that follows was told to me by two women, one a Polish Jew named Mania, the other a German Christian named Johanne. The facts recounted in Manias story, such as the time and place of her birth, her imprisonment in Auschwitz, and the murder of her mother, are true and have been documented. Her memories cannot be documented; their value lies in revealing how, as a child, she experienced and perceived the world around her. These memories are still powerful enough to influence her life today. The power of memory to determine behavior for the rest of ones life is also reflected in Johannes story. Set within the same time frame as Manias, it reflects another but equally demented world. Johannes tale is that of a beautiful young German woman passionately in love with an officer of the Third Reich. I have been able to verify some of Johannes story, such as her birthplace and family life and some aspects of her love affair, but little else because of the destruction of documentation either by Allied bombing or the Nazis attempt to cover its depraved behavior. Despite the differences in these two stories, the lives of both Mania and Johanne are linked. The extent to which they are linked is the subject of this story. I can only repeat what they told me and leave it to you, the reader, to come to your own conclusion.

My involvement with both women began in mid-2001 when I received an e-mail from Suzanne DePoe, a film agent in Toronto. Id had contact previously with Suzanne, once during negotiations for the film rights of my book Uncommon Will: The Life and Death of Sue Rodriguez, and again when she and my former literary agent, Denise Bukowski, were in negotiations for the film rights of my book Such a Good Boy. On the rare occasions I received an e-mail from Suzanne DePoe, I paid attention.

This e-mail read:

Hi Lisa. A documentary filmmaker in Vancouver wants to do a book at the same time as a doc about a woman who is a holocaust survivor who was in various camps aged 7-12. In the last camp a nazi guard took care of her, gave her food and special care and offered to adopt her after the war.

Fast forward to 1976. The girl is now a woman living in Toronto. The woman hires a cleaning lady who turns out to be the same nazi guard.

This is all the info I have. Would you be interested in exploring it further?

At the time I was not working on anything. My husband had died the previous year and I was alone. My children, like those of many North American parents, lived thousands of miles away. Id sold my home on Bowen Island, a short ferry ride from the British Columbia coast, and moved into a small waterfront apartment in downtown Vancouver. I was free to run the remains of my life as I pleased and was finding this freedom to be a wonderful, if seldom mentioned, part of widowhood.

I reread the e-mail and felt myself drawing back. Id never considered retiring from writing, but a story like this, if there was any truth to it, would mean dealing with depressing material. Id set up a cozy, comfortable life and wanted no part of anything that threatened it. Enough of my life had been spent asking the big and ultimately unanswerable questions. Id been raised in Australia as a Catholic, a faith that formed my belief that life was essentially a spiritual journey and that I was merely a tourist going through it. As for ultimate answers, Id concluded that the church didnt have them all by a long shot, and that trust under all circumstances was the only ultimate answer.

My previous two books had dealt with death, although the strange allure of that subject had played out in different ways. In one case, a seventeen-year-old high school student named Darren Huenemann, told by his mother and grandmother of the fortune he would inherit on their deaths, coaxed two high school friends to murder them.

Shortly after finishing this book, Sue Rodriguez phoned. Sue was a high-profile victim of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) who, until her own death, fought up to the Supreme Court of Canada for the right of assisted suicide. Sue had star quality and, having become the icon of the Right to Die movement, wanted her story written. I was hesitant. Assisted suicide was a quagmire of moral and legal issues, one that provoked extreme emotional reactions for or against. I told Sue I disagreed with her pro-euthanasia stance but was aware I wasnt walking in her shoes. Even as I expressed disagreement, I felt that if I had a terminally ill child in exquisite, uncontrollable painpain that I have experienced through trigeminal nerve attacksI would want a doctor to end it.

Finally I went ahead with the book, driven as much by Sues desperationher speech was becoming unintelligibleas by my need to find some sort of practical and moral answer: Were there extreme cases when mercy killing could not only be justified but actually be the right thing, the moral thing, to do? Sue put herself into the extreme case category. I did not. Id known too many Darren Huenemanns to ever support state-sanctioned killing, known too many older people in severe pain who still chose life rather than death. Id also watched for weeks while a friend died in agony, the pain of bone cancer impervious to the best medical and palliative care.

Watching the effects of ALS subtly and relentlessly embrace Sues elegant body saddened me profoundly. Throughout the long hours of our talks, as the leaves turned gold and winter moved in with its own darkness, she sat rigid, imprisoned in her electric wheelchair, as if already mummified. I bit my tongue against the hollow words of comfort that tried to inject themselves into our talks. Sue wanted only for me to listen. Her mind was set on death. The only solace she sought was my tuning body and soul into her anguish. Thats what I did. I let it become part of me.