Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East Seventh Street

New York, New York 10003

Visit our website at www.papress.com

2010 Princeton Architectural Press

All rights reserved

13 12 11 10 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

23 Heres Looking at You, 2009, Bosque School, Albuquerque, NM. Sponsored by The FUNd at the Albuquerque Community Foundation.

45 Out of the Box, 2009, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC

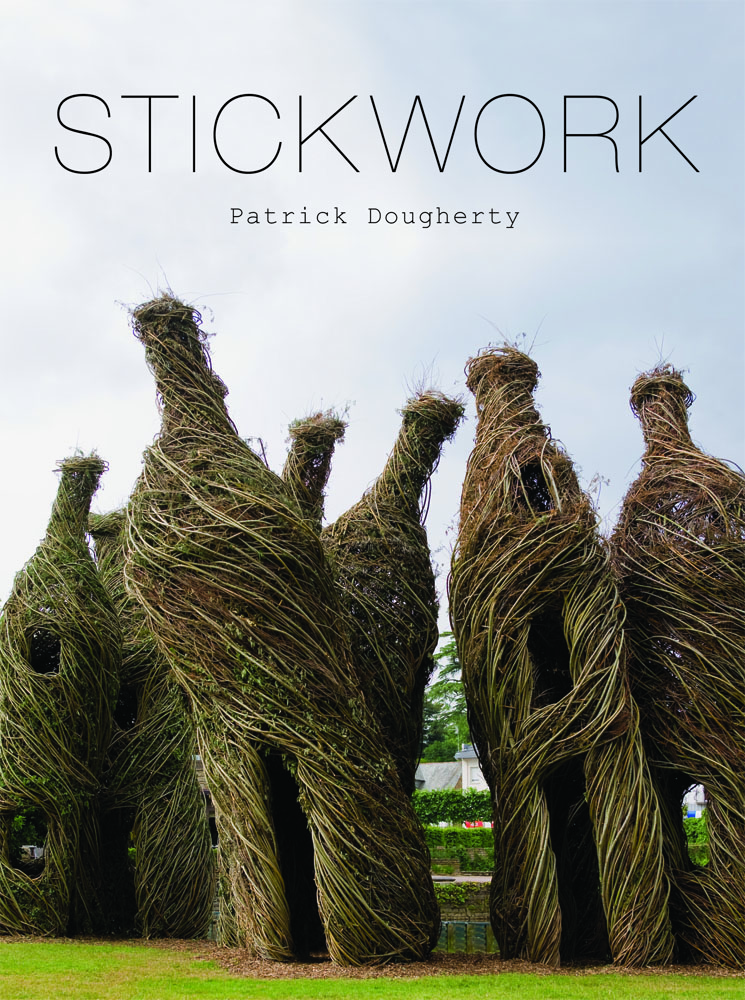

6 Huddle Up, 1993, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, England

89 Summer Palace, 2009, Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

10 Creature Comforts, 2008, Colorado College, Colorado Springs, CO

Editor: Linda Lee

Designer: Jan Haux

Special thanks to: Nettie Aljian, Bree Anne Apperley, Sara Bader, Nicola Bednarek, Janet Behning, Becca Casbon, Carina Cha, Tom Cho, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Carolyn Deuschle, Russell Fernandez, Pete Fitzpatrick, Wendy Fuller, Laurie Manfra, John Myers, Katharine Myers, Steve Royal, Dan Simon, Andrew Stepanian, Jennifer Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton Architectural Press

Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

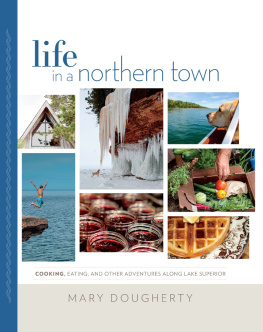

Dougherty, Patrick, 1945

Stickwork / Patrick Dougherty. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-56898-862-7 (hc.) ISBN 978-1-56898-976-1 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-61689-195-4 (Digital)

1. Dougherty, Patrick, 1945 Themes, motives. 2. Plants as art material United States.

3. Site-specific sculpture. I. Title.

NB237.D68A4 2010

730.92dc22

2009050120

Contents

by Jennifer Thompson

Selected Projects

I love to make things, and as a child I bugged my mother by constantly declaring, I bet I could make that about everything from bicycles to rock gardens to a new pair of shoes. When I decided to pursue postgraduate work in the art department at the University of North Carolina, I was surprised to find so many others like me, dedicated people who love working with materials and seeing their ideas realized. As a novice sculptor, I learned the ropes from more developed artists at Center Gallery, an artist-run space in Carrboro, North Carolina. In addition, I received enormous encouragement from my friends, Scott Bertram, the Juhlin family, Christy Lee, Mike Cindric, Dawn Barrett, and my sister, Kate Farrell. During this formative time, I met Susan Peterson, a visiting professor to UNC, who mentioned that the only requirement for becoming a national artist was the willingness to be in the nation. Soon I set sail on a bigger sea, realizing that full-time work would mean constant travel.

Taking advantage of a new art trend of building sculptures on location, I began to work on-site for museums, artist-run spaces, sculpture parks, gardens, and private individuals around the United States and then farther afield. I initially exported saplings from North Carolina to other places, using a truck and trailer purchased with money from a North Carolina Arts Council artist fellowship. However, I quickly found that the typical cycle for urban expansion meant that I could find a supply of saplings in almost every community; that is, when forests are cut at the edge of town, the scrubby regrowth is available until the bulldozers arrive for final clearing.

I would like to thank all the organizations who have sponsored me over the years. It has been a wonderful adventure and a rich learning experience. I also offer heartfelt thanks to all those who have reached out to me in every communit y the hundreds of people who have volunteered their time to help with the logistics or actually bend the sticks into place. Finally, hats off to all the passersby who stopped to look at the work and chat with me about their reactions to sculpture and other important issues. These encounters made the travel worthwhile and had a profound influence on the course of my work. Closer to home, I would like to thank my wife, Linda, for her encouragement over the years and my assistant, Dorothy Juhlin Bank, for all her hard work in the preparation of this book.

Jennifer Thompson

Everyone has a stick story. It may be as simple as how our family collects kindling when walking through the woods, or about the tepee we made as kids by leaning sticks up against a tree to create a secret hiding place, or a collection of bird nests found in the forest, each remarkable in the way small branches have been intricately woven into a lightweight basket capable of holding a family of small creatures, protecting them from rain, wind, and predators.

There is something elemental, almost primal, in the appeal of sticks and their parents, trees; their history precedes our own, and they have been mans constant companion since the earliest days, as shelter, nourishment, and fuel. Several trees alive today are more than four thousand years old, and the oldest known living organism, a Quaking Aspen in Utah, is believed to be as much as eighty thousand years old. No wonder the human connection to trees is, in many cultures, a spiritual one, symbolic of both life and immortality. Ancient trees like the Pion Pine take on deep spiritual meaning for many cultures and have come to epitomize humankinds deep dependence on trees. In Genesis the tree represents both life and knowledge. In Egyptian mythology, the acacia tree of the goddess Saosis is seen as the tree of life as well as the birthplace of deities. The world tree, a tree that connects the heavens with earth and is rooted in the underworld, is found in the iconography of most Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures as well as in Hungarian, Norse, and Finnish mythologies. In Chinese lore, the peach tree that bears fruit every three thousand years offers eternal life to the one who eats it. In India, two varieties of fig trees, the banyan and the peepal, are revered as the trees of life. More interesting is the myth of the Green Man, a figure found in many variations and cultures throughout the world. The Green Man is an artistic work of a face made of leaves, often including other types of foliage, such as vines, branches, and flowers. These works are common on church facades symbolizing rebirth and the changing of the seasons. People take their sticks seriously, and always have.