INTRODUCTION

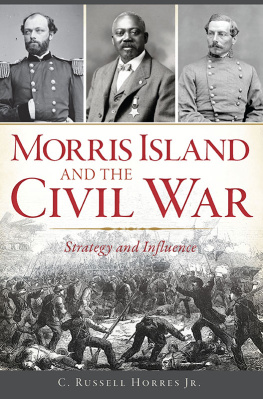

The Civil War marked a significant increase in cooperation between the Army and Navy. The evolution of this cooperation can be readily seen in the series of operations conducted by Federal forces along the Confederate coast. Beginning with modest operations, in which the Navy dominated the battle and the Army provided an occupying force afterwards, these endeavors grew into truly amphibious assaults with land and naval forces working in tandem. Taken together, these operations can be viewed as comprising a campaign engineered and supervised by a novel creation called the Navy Board, and reflecting a major step in the evolution of joint warfare and planning in U.S. military history.

The operations took advantage of both the superior Federal Navy and the revolution in naval warfare wrought by steam power. They allowed the Federal force to maintain the initiative by determining the time and the place of the attack, and compelled the Confederates to tie up many forces defending the myriad of possible Federal objectives along the vast Southern Coast. At the same time, the operations reflected Federal priorities and the need to allocate finite resources.

The operations were also an important and effective part of the Federal strategy against Confederate logistics. While the Navy blockaded Southern ports, the Army both held terrain and severed rail communications. It was a powerful combination. The result was that as Confederate logistics were weakened, Federal logistics were strengthened.

Rather than being a haphazard consequence, this outcome was the result of some very deliberate effort. Although the Federal commanders did not have the benefit of modern joint doctrinal publications, their actions with regard to the coastal war can be viewed in light of the same considerations todays military planners use when developing a campaign.

Campaign planning is the process whereby combatant commanders and subordinate joint task force commanders translate national or theater strategy into operational concepts. The national strategy relevant to the Civil War coastal campaign was articulated in April 1861, when President Abraham Lincoln declared a blockade of the Confederacy. Lincolns goal was to isolate the Confederacy and deny it the diplomatic, informational, military, and economic benefits it would gain from international commerce and access. A special planning body called the Navy Board was convened in June 1861, to develop an effective means of implementing this national strategy.

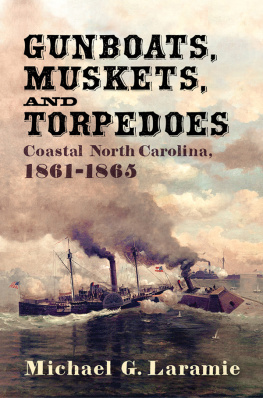

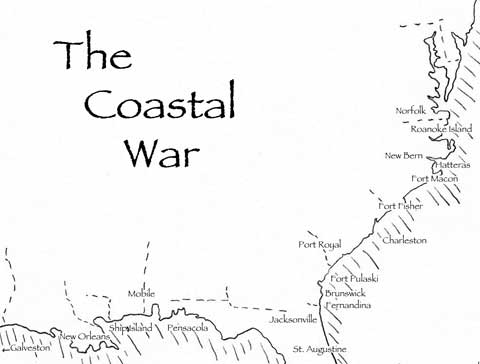

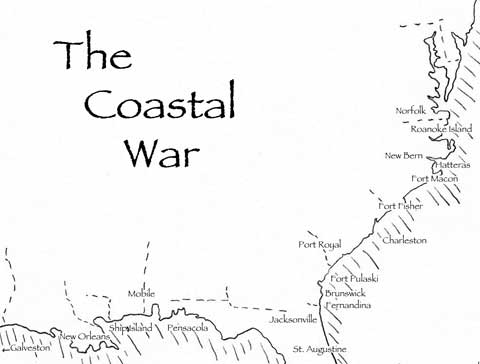

To help counter the massive scope of the Confederate coastline, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles initially divided responsibility between two squadrons, the Atlantic Blockading Squadron and the Gulf Blockading Squadron. The Atlantic Blockading Squadrons area of operations stretched from Alexandria, Virginia to Key West, Florida. The Gulf Blockading Squadrons responsibilities ranged from Key West to the Mexican border. This particular study will examine four distinct campaignsthe Atlantic Blockading Squadrons campaign on the Atlantic, Brigadier General Ambrose Burnsides Expedition along the North Carolina coast, the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, and the Gulf Blockading Squadrons campaign on the Gulf.

Campaigns are a series of related major operations aimed at accomplishing strategic and operational objectives within a given time and space. The operations along the Confederate coast all were related in their pursuit of the Federal strategy of isolating the Confederacy. The Atlantic Campaign consists of operations at Hatteras Inlet, Port Royal Sound, Fernandina, and Fort Pulaski. Burnsides Expedition includes Roanoke Island, New Bern, and Fort Macon. By design, the Peninsula Campaign was more of a land attack on Richmond than a part of the coastal campaign, but one of its fringe benefits was the Federal reoccupation of Norfolk, so it is included in this study. The Gulf Campaign involves Ship Island, New Orleans, Pensacola, and Galveston. Three other operations that are part of the overall coastal campaign but proved more difficult challenges for the Federals are Charleston, Mobile Bay, and Fort Fisher, which guarded the Confederate port of Wilmington. These will be discussed as separate operations to highlight their chronological separation from the rest of the campaign.

Although seemingly a hodgepodge of indiscriminate battles, the coastal war was actually a well-planned campaign to systematically gain control of the Confederate coast.

Certain themes emerge from each of these campaigns. They include the utility of the Navy Board and its efficiency in planning means of strengthening the blockade, competition for finite resources, a failure to capitalize on success, and various issues involving joint operations and unity of effort. Admiral Samuel Du Ponts Atlantic Campaign is singularly important because it would not be until Major General Ulysses Grants Vicksburg Campaign of 1863 that another Federal commander conducted a true campaign that successfully achieved a clearly defined strategic objective; in Du Ponts case tightening and improving the blockade. Burnsides Expedition is important because it marks the growing role of the Army in coastal operations. The Army would no longer merely occupy what the Navy had compelled to surrender, but would now project power inland and further weaken Confederate logistics. The objective of the Peninsula Campaign was Richmond, and it failed in this regard, in part because of a lack of unity of effort between the Army and the Navy. However, by reoccupying Norfolk, the Peninsula Campaign was beneficial to the Atlantic Blockading Squadron. The centerpiece of the Gulf Campaign was capturing the key city of New Orleans. Federal possession of New Orleans not only reduced blockade running, it was also a major step toward controlling the Mississippi River and cutting the Confederacy in two. The Gulf Campaign allowed the Federals to take the war to the Deep South long before an overland advance was possible.

Each specific operation within the campaigns also offers its own unique lessons for the student of joint operations, as well as showing a stage in the evolution of Army-Navy capabilities and cooperation. In the Atlantic Campaign, Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina, was the first such venture attempted, and it was appropriately limited in scope. It was by far a Navy-dominated affair, and one in which the possibilities of the steam engine began to become apparent.

Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, was much more ambitious and reflected the Federals growing confidence in coastal warfare. Even more so than Hatteras Inlet, Port Royal Sound was a Navy show. Indeed, it was one that clearly demonstrated just how much the steam engine had altered the historic balance between the ship and the fort.