Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Frank Ofeldt

All rights reserved

E-Book year 2020

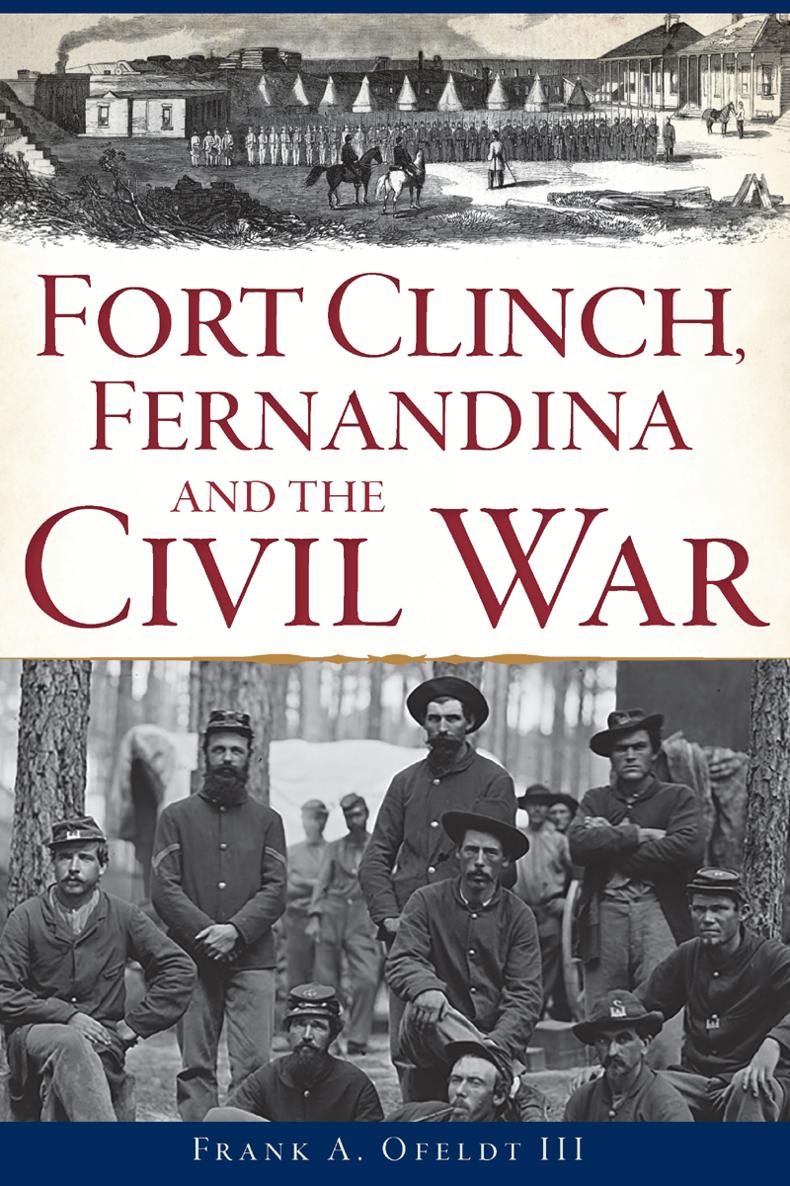

Front Cover

Top: A newspaper artists drawing of the interior of Fort Clinch just days after being captured by federal forces. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

Bottom: Companies C and E, First New York Volunteer Engineers carried out the construction of Fort Clinch. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

First published 2020

ISBN 978.1.4396.7078.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020938459

Print Edition 9781467145961

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To my wife, Samantha, for her support and encouragement and for the many times my love of history came first. And to Mom and Dad, who gave me a compass to follow.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the many friends and associates who offered their help to bring this book into production. I want to thank the State of Floridas Archives for the many times they provided me with the documents I needed to fill in the gaps. I also need to thank the Library of Congress, the National Archives and their outstanding institutions for providing me with a wonderful opportunity to view the many papers, articles and documents related to the Civil War. I would like to extend my thanks to the Center for Military History, the United States Army Corps of Engineers and the United States Military Academy for the information they provided. Professor Penny Sansbury deserves my thanks for her knowledge of writing and literature, which led her to assist with the manuscript editing. I would also like to thank her husband, Steve Sansbury, for being an outstanding friend and fellow Civil War historian and for his free counseling on matters of great importance. I want to thank my coworker and close friend Andrew Smith for his input and knowledge of political science and how Civil War politics played out. I also want to thank Jennifer England for her help with images and her grandfather Howard England for taking the time to share his passion and love of Fort Taylor, where my career with the Florida Park Service started. My friend Mary Agnes White, who provided me with many letters and images of Fort Clinch before her passing, also deserves my thanks. I would also like to thank my friend and author Lewis G. Schmidt for all the documents he provided over the years. I thank Dicky Ferry for the wonderful original letters, documents and images he provided. Lastly, I would like to thank the Amelia Island Museum of History for the wonderful historic collection it preserves and the many living historians who volunteer to keep history alive at Fort Clinch and who recognize the role it played during the Civil War.

INTRODUCTION

Floridas role in the American Civil War was small compared to other southern states. The state population was a mere 140,424, according to the 1860 census, with 61,745 classified as slaves. The largest towns were Marianna, Apalachicola, Pensacola and Quincy, followed by Tallahassee, Monticello, Madison, Fernandina, Ocala, Gainesville, St. Augustine and Key West. After becoming the twenty-seventh state to join the Union on March 3, 1845, the state played a major role in the Civil War as the chief provider of beef cattle and salt for the Confederacy. Florida was known as the smallest tadpole in the dirty pool of secession. Although Florida was not a large cotton producer like its neighbors, it still produced the crop in the region that ran from Ocala in north central Florida to Marianna in the northwest. Floridians at the time had a strong stance on the issue of states rights. With disputes over economics, political differences and slavery, the steam over the issue was building up, and the top was about to blow off.

With the election of Abraham Lincoln as the sixteenth president of the United States, Floridas path was clearly shown. Most Floridians supported southern democrat John C. Breckenridge, who received a vote of 8,543, and Unionist candidate John Bell received 5,437 votes. Fernandinas voting male population strongly supported the southern Democrat and the course of action of secession that was about to play out. The Civil War would become the greatest conflict the nation would endure during the nineteenth century. Even to this day, over 150 years later, Americans still debate the causes of the war and attempt to understand it.

One thing about the war that stands out for most is the loss of life that occurred. The Civil Wars casualties were horrific, with almost one million dead and many others who suffered from long-lasting physical and psychological effects. The war affected just about every American, from those in the largest cities to those in the smallest towns, and its impact can still be felt todayeven on Amelia Island, a place of sun and fun, where island time is the motto. The remains of the war can be seen in the places that the citizens of Fernandina called home so many years ago. Amelia island is the northernmost barrier island on Floridas east coast and has been a place that has seen great strife and sacrifice from its citizens since the first Europeans arrived there.

In 1811, the town of Fernandina, which is located on Amelia Island, was plotted by the Spanish during their second period in Florida, from 1783 to 1821. Today, there are two towns located on Amelia Island, both New and Old Fernandina. Old Town was founded in 1811, and New Town was founded in 1853 and remains today. The histories of these towns are unique; Fernandina was once a thriving seaport that boosted commerce trade, smuggling, slavery and profiteering. The town was named for King Ferdinand VII in 1811; at the time, he was prisoner of the French, but after the defeat of Napoleon, he regained the Spanish throne in 1814. Old Fernandina was a gem of a town, with grid-pattern streets and a location overlooking the Amelia River. The river was the towns lifeline to the world, where the ships brought forth the goods for the survival of citizens and the town itself.

Being a gem comes with envy, and in 1807, the United States instituted an embargo on all foreign goods entering the country. And a year later, in 1808, the importation of slaves to America was banned. Fernandina became a hot spot for smugglers, slavery and piracy until the embargo was lifted. Anything a heart desired could be found in Spanish Fernandina. In 1812, the Patriots overthrew the Spanish and captured the town; however, their occupation was short lived, and American forces took custody of Fernandina until the Spanish authority could be reestablished.

In June 1817, the Scottish mercenary Sir Gregor McGregor seized Fernandina and Fort San Carlos from the Spanish and raised the green cross flag of the Republic of Florida, liberating the island and its citizens from Spanish rule. However, with dwindling forces and finances, McGregor was forced to give up his conquest. Two Americans working alongside him seized leadership of the remaining forces and intended to maintain independence from Spain. Ruggles Hubbard, a former sheriff of New York, and Jared Irwin, a former congressman of Pennsylvania. The Spanish began to bombard Fernandina and Fort San Carlos, which were held by Irwin, Hubbard and their Republic of Florida forces of only about ninety men. The Spanish gunboats commenced firing just after 3:00 p.m., and the battery of Spanish cannons at McClures Hill joined in. The cannons of Fort San Carlos defended Amelia Island against the Spanish assault, with Irwins forces inflicting casualties on Spanish troops that were concentrated below McClures Hill, destroying a portion of their cannon powder supply; however, firing continued until dark. The commander of Spanish forces, convinced he could not capture the island or force Irwin to yield, was forced to withdraw, leaving Fernandina and the island in the hands of Irwin and Hubbard.