THE ORIGIN OF THE RING

T HE origin of the ring is somewhat obscure, although there is good reason to believe that it is a modification of the cylindrical seal which was first worn attached to the neck or to the arm and was eventually reduced in size so that it could be worn on the finger. Signet rings were used in Egypt from a very remote period, and we read in Gen. xli,42, that the Pharaoh of Josephs time bestowed a ring upon the patriarch as a mark of authority. From Egypt the custom of wearing rings was transmitted to the Greek world, and also to the Etruscans, from whom the usage was derived by the Romans. The Greek rings were made of various materials, such as gold, silver, iron, ivory, and amber.

In his Natural History, Pliny relates the Greek fable of the origin of the ring. For his impious daring in stealing fire from heaven for mortal man, Prometheus had been doomed by Jupiter to be chained for 30,000 years to a rock in the Caucasus, while a vulture fed upon his liver. Before long, however, Jupiter relented and liberated Prometheus; nevertheless, in order to avoid a violation of the original judgment, it was ordained that the Titan should wear a link of his chain on one of his fingers as a ring, and in this ring was set a fragment of the rock to which he had been chained, so that he might be still regarded as bound to the Caucasian rock.

Another origin ascribed to the ring is the knot. A knotted cord or a piece of wire twisted into a knot was a favorite charm in primitive times. Frequently this was used to cast a spell over a person, so as to deprive him of the use of one of his limbs or one of his faculties; at other times, the power of the charm was directed against the evil spirit which was supposed to cause disease or lameness, and in this case the charm had curative power. It has been conjectured that the magic virtues attributed to rings originated in this way, the ring being regarded as a simplified form of a knot; indeed, not infrequently rings were and are made in the form of knots. This symbol undoubtedly signified the binding or attaching of the spell to its object, and the same idea is present in the true-lovers knot.

Many rings of the Bronze Age were found in the course of excavations conducted in 1901 by M. Henri de Morgan in the valley of Agha Evlar, stretching back from Kerghan on the Caspian Sea, in the region known as the Persian Talyche. Here several sepulchral dolmens were discovered which yielded a considerable number of ornamental objects of metal and stone, as well as beads of vitreous paste. There was no trace of inscriptions to aid in dating these Scythian finds, but they are considered to belong to the second millennium before Christ. The bronze rings are of several different types, some of them showing from three to five spirals; in other cases the ends are overlapping, or else brought together as closely as possible.

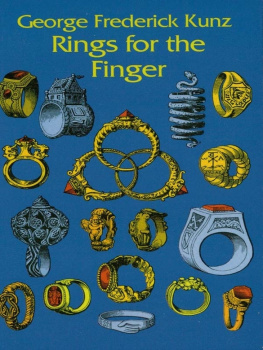

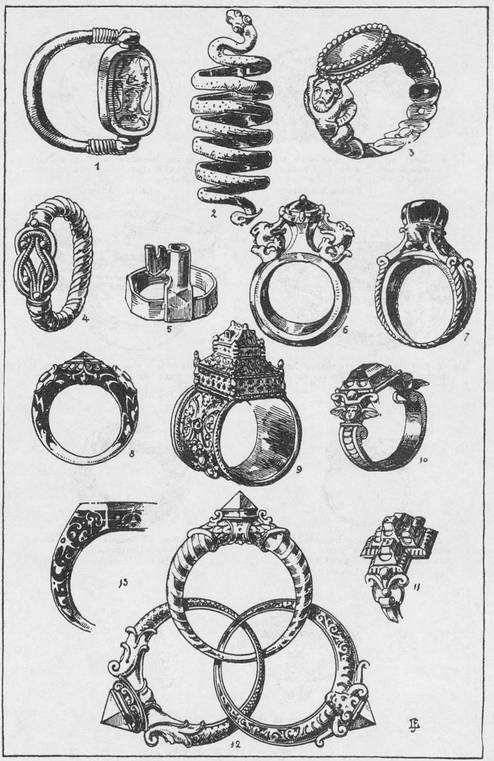

EVOLUTION OF THE FINGER RING

1, Egyptian seal ring. 2, Greek snake ring, found at Kertch in the Crimea. 3, antique Roman ring (Berlin Antiquarium). 4, Romano-Etruscan ring. 5, Roman key ring. 6, Gothic ring with stone set on raised bezel. 7, Gothic ring with cabochon-cut stone. 8, Renaissance ring with enamel decoration. 9. Hebrew wedding ring. 10, Renaissance ring. 11, Renaissance ring. 12, coat of arms of the Medici, three interlinked stones, each set with a natural pointed diamond crystal

Large serpentine ring with many coils. Gr  co-Roman, Fourth Century B.C. to Second Century A.D.

co-Roman, Fourth Century B.C. to Second Century A.D.

British Museum

Gr  co-Roman silver ring, set with an oval engraved sardonyx. Second Century A.D.

co-Roman silver ring, set with an oval engraved sardonyx. Second Century A.D.

British Museum

Greek gold ring with eye-shaped bezel.

From Tarsus; Third Century A.D. British Museum

Hellenistic bronze ring. Bezel set with a convex pale green paste. Remains of gilding on ring

British Museum

Greek silver ring. Engraved design beneath a sunk border; draped figure of a girl holding out a dove

British Museum

Roman ring of opaque dark glass. Fourth Century A.D.

British Museum

Mycen  an gold rings. 1, from Ialysos, Rhodes; given to the British Museum in 1870 by John Ruskin; 2, from excavation at Enkomi, 1896

an gold rings. 1, from Ialysos, Rhodes; given to the British Museum in 1870 by John Ruskin; 2, from excavation at Enkomi, 1896

British Museum

Although it would scarcely be safe to assume that finger-rings were never worn by the ancient Assyrians, still the almost total absence of representations of them, even on female figures, renders it safe to say that this must have been only very rarely the case. Possibly the persistence in Assyria and Babylonia of the cylindrical form of seal may account for this, in part at least, for the signet ring in many places was evolved from the cylinder-seal. Moreover, the absence of small intaglios in the period earlier than 500 B.C. would have deprived a ring of its almost essential setting. The plates in Layards great work on Assyrian remains, as well as those published by Flandrin and Coste, also offer strong negative evidence, although Dr. William Hayes Ward states that he would have expected finger-rings might have come from Egypt by the way of Syria. At a later period, under Greek influence, rings were not uncommon. In the immense cemeteries at Warka and elsewhere numerous iron rings have been found, many of them toe-rings, as well as some made of shell, but the date of these burials is not easily determined, and they are probably, in most instances, not of much earlier date than the eighth or even the sixth century before Christ.

A proof that genuine antiques can still be picked up in our day in the East is given by Doctor Ward, who said that he bought in Bagdad a lovely gold ring set with a cameo on which was inscribed in Greek characters Protarchus made it. When, on visiting London, he told this to Doctor Murray, of the British Museum, the latter gave full expression to his scepticism, saying, There are plenty of those signed things. But when the gem itself was shown him, he exclaimed, This is jolly genuine, and he had it photographed for his book.

co-Roman, Fourth Century B.C. to Second Century A.D.

co-Roman, Fourth Century B.C. to Second Century A.D.