Duncan Lunan Astronomers' Universe The Stones and the Stars 2013 Building Scotland's Newest Megalith 10.1007/978-1-4614-5354-3_1 Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

1. Archaeologists Versus Astronomers

I looked out over the Moss and tried to imagine life in those days, almost four millennia ago, 200 generations of men away from us. From air photos, I knew that apart from the stone circles, the Moor was covered with hut circles; the whole area must have supported a largeish community of fishermen, hunters and primitive farmers. And at night, the only illumination would be the stars and the Moon and the fires before the huts. No TV, no adverts. Perhaps for the first time I began to appreciate the appeal these stones, the long cultural echoes of the ancient people of Arran, could have. Archie Roy, Deadlight [].

In archaeology, the idea that ancient standing stones and circles were astronomically aligned and accurately so is extremely controversial, if not rejected outright. Among astronomers, if not universally accepted, the idea is at least treated with greater sympathy. Members of the public, who are perhaps more generally interested in things astronomical than in the relatively staid work of archaeologists, may be surprised to learn that prehistoric astronomy is not viewed by all scientists as proven fact. Many people may believe, wrongly, that the Druids built Stonehenge; guess that they are up to 3,000 years old; may not even know that there are other such sites; and yet are in no doubt at all that Stonehenge and the pyramids were observatories of some kind. In arguments about gods from outer space, or UFOs, its virtually taken for granted that the ancient sites relate to the sky.

The opposing views gained prominence in 1967; 10 years later, the argument had not been settled, but was continuing with growing heat. In 1980, fuel was still being added to the flames. Meanwhile the Glasgow Parks Departments Astronomy in the Parks project was not intended as a contribution to the debate so much as a comment on it, by a small group of people who definitely did support the astronomical interpretation of the ancient sites. To date, that comment has not influenced the debate its point is perhaps a subtle one but it may have an effect in time. Meanwhile, ongoing events at the circle have provided lessons on what could and could not be done at the ancient sites.

At Stonehenge, in the 1960s, the literature available at the nearby souvenir shop without exception placed some emphasis on the alignment of Stonehenge to midsummer sunrise, while stressing that there was no evidence to support modern names for features such as the Altar Stone and Slaughter Stone []. There was nothing to counteract the impression that Stonehenge had functioned at least partly as an observatory.

Behind the scenes, however, controversy was building up. In 1963 C.A. Newham and Professor Gerald Hawkins, working independently, had published interpretations of alignments at Stonehenge indicating a lunar observatory function as well as a solar one [].

In 1965 Prof. Hawkins published an enlarged version of his account, with anecdotes and speculation, in his book Stonehenge Decoded [].

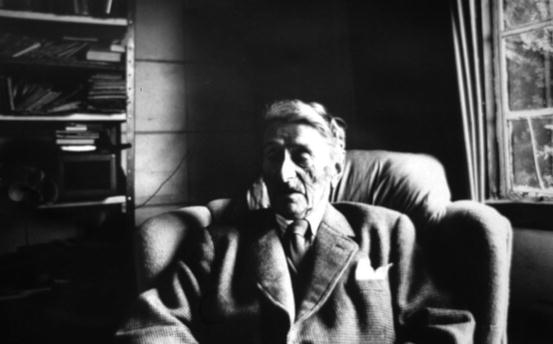

Alexander Thom, professor of Engineering Sciences at Oxford (Fig. ]. They could hardly have been more different in tone from Stonehenge Decoded , but their opponents treated them as all of a kind.

Fig. 1.1

Professor Alexander Thom at his home in Dunlop, Ayrshire (Photo by Gavin Roberts, 1978)

From Thoms studies he concluded that the ancient builders had been engaged in a long-term program of lunar observations, tracing the Moons complex movement in the sky with a thoroughness and precision going far beyond the needs of the calendar or of any imaginable ritual. Along the way it seemed that the megalithic astronomers would have realized that Earth is a sphere and discovered the slow wobble of Earths axis, which we call the precession of the equinoxes. Since many archaeologists were already committed to the position that the Stonehenge alignments were coincidental, Thoms thesis met with widespread hostility. It was perhaps unfortunate that at that time the Thoms surveys had not so far included Stonehenge itself: critics tended to lump all the astronomical theories together, as if arguments against one applied to all, whereas in fact there were very important differences between Thoms claims and those made by Hawkins, followed by Sir Fred Hoyle [].

Within the relatively compact boundaries of Stonehenge, Hawkins had allowed the postulated astronomical alignments to be wide of the mark by as much as a degree and a half, either way, altogether six times the apparent diameter of the Sun or the Moon; however, the sites that Thom had studied were alleged to show very careful exploration of the landscape, lining up astronomical events with features on the horizon to an accuracy of a few minutes of arc. And whereas Hawkins and Hoyle maintained that Stonehenge was a computational device, used to predict eclipses, Thom was claiming that the sites he surveyed were the product of an observing program, locating each alignment precisely on the ground before it was immortalized in stone. The sophistication which then followed, in the layout of the various types of stone rings, was pure mathematics based on right-angled triangles and inspired by a wish to make the key dimensions multiples of a standard unit of length.

The hostile reaction of the archaeologists to the new discipline generally called astroarchaeology or archaeoastronomy, according to the background of the speaker was directed to both sides of the question. The astronomy involved was alleged to be far too subtle for Neolithic people involved in a daily struggle for survival, possessing no metal tools, instruments or even the art of writing. But the principles involved are not that hard to grasp (see below) and the mathematics are only of first-year undergraduate level. One can sympathize with an archaeologist with a liberal-arts background who finds them hard going, but not if the objection takes the form that ancient Man couldnt have done anything I dont understand.

Far more to the point, however, is that the calculations are needed only to set back the clock of Earths shifting axis, back to prehistoric times. The Neolithic observer did not need to calculate where the Sun rose at the solstice of 2700 b.c. , because he could watch it! It is no coincidence that megalithic astronomy is widely accepted by amateur astronomers, who spend their nights watching for meteors or aurorae with the naked eye or with small telescopes. To the prehistoric Britons, occupying a sparsely populated island thousands of years before the invention of the street lamp, with generally better weather due to heightened solar activity between 3000 and 2000 b.c. [], the sky overhead was anything but an abstraction.

Referring to the star lore of pre-Columbian Central America, and its possible survival in Amerindian cultures, Michael D. Coe wrote: This area has hardly been touched, and the reasons are not hard to find. In the first place, there is scarcely an ethnologist or social anthropologist who can identify anything other than the Moon or the Big Dipper in the night sky; the so-called natives are a great deal wiser [].

Just two examples may serve to underline that point. In Aubrey Burls comprehensive book Prehistoric Avebury (1979), he cites and accepts some evidence of astronomical alignments, but goes on: That the rituals involving human bone at Avebury were held in the darkness of the night is unprovable but the fact that its two Coves, themselves in the likeness of tomb entrances, were connected with the night, the North Circle Cove facing towards the moons most northerly rising, the Cove at Beckhampton towards the sunrise at midwinter, suggests that nocturnal winter activities were performed here. Whether, then, from the west along the Beckhampton Avenue or southwards from the Sanctuary, one can imagine torchlit processions as the Moon rose which he goes on to imagine in detail. But the Moon rises at its most northerly position, not at every midwinter, but only once every 18.61 years. For about a year either side, the Moon would rise near enough to that position for ritual purposes but often in daylight, seldom if ever at the Full, and not at midwinter unless by pure chance, and even then, not to be repeated for centuries.