1. Comets

Abstract

So the star, with the pale moon in its wake, marched across the Pacific, trailed the thunder-storms like the hem of a robe, and the growing tidal wave that toiled behind it, frothing and eager, poured over island after island and swept them clear of men: until that wave came at last in a blinding light and with the breath of a furnace, swift and terrible it came a wall of water, fifty feet high, roaring hungrily, upon the long coasts of Asia, and swept inland across the plains of China.

So the star, with the pale moon in its wake, marched across the Pacific, trailed the thunder-storms like the hem of a robe, and the growing tidal wave that toiled behind it, frothing and eager, poured over island after island and swept them clear of men: until that wave came at last in a blinding light and with the breath of a furnace, swift and terrible it came a wall of water, fifty feet high, roaring hungrily, upon the long coasts of Asia, and swept inland across the plains of China. For a space the star, hotter now and larger and brighter than the sun in its strength, showed with pitiless brilliance the wide and populous country; towns and villages with their pagodas and trees, roads, wide cultivated fields, millions of sleepless people staring in helpless terror at the incandescent sky; and then, low and growing, came the murmur of the flood. And thus it was with millions of men that night a flight no whither, with limbs heavy with heat and breath fierce and scant, and the flood like a wall swift and white behind. And then death.

H. G. Wells, The Star

What H. G. Wells has envisaged here is not a collision with Earth but a stray planet from interstellar space colliding with Neptune with enough force to hurl the combined incandescent mass sunwards [1]. When he published The Star in 1897, the scientific view was that the impact of a comet would do no physical harm. His novel In the Days of the Comet (1906) brings a comet upon us with no actual impact, the gases mixing peacefully with Earths atmosphere [2]. There is a mysterious constituent, revealed before the encounter by a green line in the comets spectrum, but thats just a device by which to change the character of the human race and bring in a socialist utopia. Earth passed through the tail of Halleys Comet in 1910 without harmful effects, not even creating a utopia, and in 1913 The Poison Belt, one of Sir Arthur Conan Doyles Professor Challenger stories, imagined simply a cloud of gas in space, without a comet to generate it [3]. But the effects of an actual impact by a large comet or asteroid would be analogous to what Wells described, as we shall see.

The nearest approach to a major comet scare came when Comet Swift-Tuttle (the Great Comet of 1862) was expected to return in late 1982. The possibility that it might hit Earth made waves in amateur astronomy, professional astronomy, the media, the political sphere, and the military-industrial one; and it was interesting that the various groups seemed hardly to be talking to one another much of the time. The whole debate about the need to protect Earth was reopened.

Swift and Tuttle were both American astronomers of the mid-nineteenth century, and both discovered several comets that were named after them. Comet Tuttle references are generally to the Great Comet of 1858 and not to the faint comet 1862 I, which he discovered in January that year but which never grew bright enough to be seen by the naked eye. On July 2, J. F. Julius Schmidt in Athens found a comet 1862 ll that was named after him.

Lewis Swift discovered 1862 III, the Great Comet of that year, on July 15 [4]. At first it was so like Schmidts 1862 II that Swift didnt realize it was different, until Tuttle independently found it and announced it 3 days later. The astronomical world split the honors, hence Comet Swift-Tuttle, but older texts often confusingly call it Comet Tuttle.

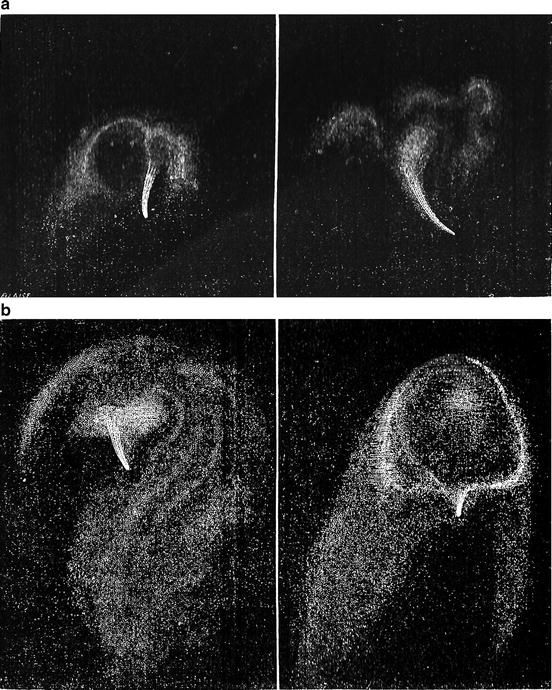

In August 1862 the comet put on a spectacular display in northern hemisphere skies, traveling past Polaris from Camelopardis and developing a tail 25 long. In the telescope it was seen to be throwing out luminous jets that looped around the more normal tail in a most unusual way [5, 6] (Figs. ). The link between comets and meteor showers was big news in the 1860s, and the apparent link with the Perseids, the best-known meteor shower of all, was enough to keep the comet in the literature for the rest of the nineteenth century, although the first two comets of the year were forgotten and it was called simply the comet or the great comet of 1862.

Fig. 1.1

Comet Swift-Tuttle, also called 1862 III (Copyright Sydney Jordan, 1994, after a nineteenth century lantern-slide loaned by John Braithwaite) [5]

Fig. 1.2

( a , b ) Observations of jets from Comet Swift-Tuttle (From Amde Guillemin, The Heavens , 1871) [6]

Fig. 1.3

Orbits of Earth and Perseid meteors (From F. Chambers, A Handbook of Descriptive and Practical Astronomy , 4th ed., 1889) [7]

The Swiss astronomer Plantamour lectured on the link with the Perseid meteors in the winter of 18711872, mentioning that Earth would next encounter the meteors on August 12, 1872. Newspapers reported that Earth would collide with the actual comet on that date, causing considerable public alarm [8]. Nineteenth-century astronomers thought such fears were groundless. Comets had passed close to Mercury, and between the moons of Jupiter, without producing any noticeable perturbations; so their masses had to be low. And Earth had passed through the tail of the great comet of 1861 without any noticeable effect, so the tails had to be tenuous gases; and when the head of one passed in front of the star Arcturus without dimming it significantly, that seemed to clinch the mattercomets were entirely gaseous. In the twentieth century it came to be accepted that there must be something inside the great heads of the comets, but whatever it was, no doubt it was too small and flimsy to be dangerous.

Science fiction writers, of course, ignore astronomers when it suits them (For example, many twentieth-century astronomers believed this was the only planetary system in our galaxy). In Off on a Comet and its sequel, Jules Verne described a comet made of solid gold telluride, so that it could knock lumps off Earth for the purposes of his story [9]. H. G. Wells stuck to prevailing theory for In the Days of the Comet , as above. In Arthur C. Clarkes short story Into the Comet, first published in 1960, the spaceship Challenger (note the name) is able to penetrate the core of a comet because its a loose cluster of dirty gray icebergs, giving off jets of methane and ammonia [10].

Clarke claimed to be quoting F. L. Whipple, but Whipple himself envisaged the dirty ice as water and as a single mass typically 110 km in diameter [11]. This authors own story, based on his amateur observations of Comet Bennett in 1970, made the nucleus a single mass of ice and rock, surrounded by shoals of drifting ice, and Isaac Asimov said that story pictures a Whipple-like comet with considerable accurate detail. [12] Within the head of Comet Bennett there was a bright blue patch surrounded by what appeared to be a diffraction pattern, and satellite observations showed the comet had a hydrogen halo 13 million km across, implying far more ice in the nucleus than the boulder or sandbank models would allow [13].