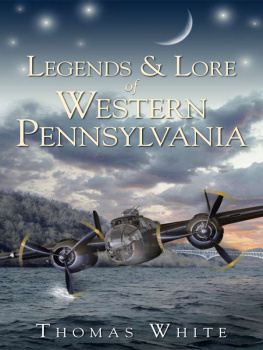

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2013 by Thomas White

All rights reserved

Front cover: Home of Nelson Rehmeyer (Hex Murder House). Courtesy of the Stewartstown Historical Society.

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.587.0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, Thomas.

Witches of Pennsylvania : occult history and lore / Thomas White.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-132-7

1. Witchcraft--Pennsylvania--History. 2. Witches--Pennsylvania--History. 3. Witches--Pennsylvania--Folklore. 4. Pennsylvania--Social life and customs. 5. Folklore--Pennsylvania. I. Title.

BF1577.P4W44 2013

133.4309748--dc23

2013022223

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For my students

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preparing this book on the history and legends of witchcraft in Pennsylvania required the help and support of many people. I want to thank my wife, Justina, and my children, Tommy and Marisa, for allowing me the time to complete this project and for their support. For their continued encouragement, I also want to thank my brother, Ed, and my father, Tom. My mother, Jean, who passed away almost two years ago, encouraged my intellectual curiosity at a young age and will always influence any project that I work on. Paul Demilio, Zaina Boulos, Michelle Bertoni, Kelsy Traeger, Gerard ONeil and Elizabeth Williams all spent time proofreading and editing for me, and their input and suggestions were greatly appreciated. Numerous librarians, archivists and historians helped me to find information and photographs, including Doug Winemiller at the Stewartstown Historical Society, Joel Alderfer at the Mennonite Heritage Center and Anna Marry Mooney, Dwight Copper and Andrew Henley of the Lawrence County Historical Society. J. Ross McGinnis, foremost expert on the York Hex Murder, graciously took the time to discuss his research with me and provide photographs. One of my students, Rachael Gerstein, shared her memories of a witch legend that she experienced growing up in Luzerne County. Her willingness to recount the story was appreciated, as was the tale of a mysterious witchcraft-related metal plate that was shared by Elizabeth Ringler and her father, Frank Bittner. I also want to thank writer and researcher Stephanie Hoover, who runs the interesting site Hauntingly Pennsylvania and who provided me with information on a Dauphin County witchcraft incident. Many other people helped in a variety of ways while I worked on this project. They include Rebecca Lostetter, Michael Hassett, Bobbie Jo and Dave Leppo, Sean Coxen, Emily Jack, Art Louderback, Emily Kustanbauter, Dr. Joshua Forrest, Kelly Bennett, Maria Yalch, Stephan Bosnyak, Tony Lavorgne, Kurt Wilson, Ken Whiteleather, Brian McKee, Dan Simkins, Brett Cobbey, Will and Missy Goodboy, Brian Hallam, Vince Grubb and the students of my spring 2013 Shaping of the Modern World class and my Global Influence of Myth class. I would also like to thank Hannah Cassilly and the rest of the staff of The History Press for giving me the opportunity to write another book with them.

Introduction

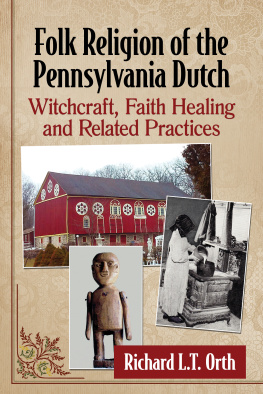

Witchcraft, Folk Healing and Hex in the Keystone State

There are few topics in history that are as widely popular as witches and witchcraft. The image of the witch has so permeated the Western imagination that almost anyone can provide at least a vague definition or description of one. Though European witchcraft is often the focus of professional historians, American culture is littered with accounts and images of witches and associated supernatural phenomena. From the well-known and extensively studied Salem Witch Trials to the Wicked Witch of the West and other stereotyped witches from literature and popular culture, it is clear that witchcraft has left its mark on the American psyche.

For many modern Americans, the study of historical witchcraft begins and ends with the Salem Witch Trials. The trials are often viewed as an anomaly by the armchair historian: an old and backward tradition carried over from Europe that was eradicated by the march of American progress and freedom. Yet this view is both historically inaccurate and deeply flawed. The belief in witchcraft existed throughout North America, and encounters with real witches were surprisingly common. Even today, though not as widespread, the belief in witches continues in a variety of forms.

Here in Pennsylvania, the state founded by William Penn and his Quaker associates, a multitude of accounts of witches and witchcraft exist. One reason for this is indirectly tied to the Quakers general tolerance for other religious beliefs and peoples. The relative freedom of religion attracted numerous German immigrants who were members of both traditional and obscure religious sects. With them, those immigrants brought a strong tradition of belief in witchcraft and the supernatural. Other settlers who came in later years also brought their own rich traditions of folk belief to the state. Luckily, Pennsylvania has a long record of preserving its folklore and history and many of these accounts of witchcraft have survived. Though such accounts are not always as thoroughly documented as scholars might prefer, they at least give us a window in which to view the occult world of our predecessors.

Witchcraft in Pennsylvania exists as part of the larger system of magical-religious folk healing and supernatural belief brought by the colonizers and immigrants. Throughout history, there have always been individuals in communities that were thought to be gifted or adept at what we would consider folk magic. Folk magic was the type of magic practiced by the common people, not the high magic of the educated sorcerers and necromancers of medieval and renaissance Europe. The practice of magical folk healing was laden with religious, primarily Christian, overtones but still contained vestiges of pre-Christian rituals. It could also contain elements of herbalism and traditional remedies. For the practitioners of this type of magic, there was no sharp distinction between religion, magic and science when it came to their work. The skilled individuals provided services to their community in the form of physical and mental healing; fortunetelling; locating lost people, animals and objects; protection; and removal of curses. In the English tradition, those practitioners were known as cunning folk. The Pennsylvania German tradition labeled them brauchers, powwowers or sometimes hex doctors. Other cultures provided them with different names, but they all performed similar functions in their social environment, and even though they dealt with what we might call occult forces, they were accepted as part of the social order.

At the far end of this magical-religious spectrum was the witch. The witch was skilled in the aforementioned practices but generally did not use them to help the community. Instead, the witch performed darker rituals to harm and harass his or her neighbors, utilizing magic to commit criminal acts. As historian Alison Games noted in

Next page