rowing the ATLANTIC

Lessons Learned on the Open Ocean

Roz Savage

Simon & Schuster

New York London Toronto Sydney

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 2009 by The Voyage LLC

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition October 2009.

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Designed by Nancy Singer

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Savage, Roz, date.

Rowing the Atlantic: lessons learned on the open ocean / Roz Savage.

p. cm.

1. Savage, Roz, date. 2. RowersGreat BritainBiography. 3. Women rowersGreat BritainBiography. 4. Atlantic Rowing Race (2005) I. Title.

GV790.92.S26A3 2009

797.123092dc22 [B]2009002326

ISBN: 978-1-4165-8328-8

eISBN: 978-1-4165-836-0-8

This book is dedicated

to anybody who has a dream

CONTENTS

rowing the ATLANTIC

one THE UNLIKELY ADVENTURER

a gale is blowing, and the small marina of La Gomera is haunted by a restless energy. The wind whistles through the yachts rigging with a whispered scream, and the halyards clank mournfully against the masts as the boats jostle and strain at their mooring ropes as if yearning to be at sea. It takes only a small effort of the imagination to picture the ghosts of ancient mariners flitting among the tethered vessels, urging them to throw off their lines and leave the safety of the harbor to dare the open ocean.

Lined up alongside a pontoon on the landward side of the marina is a cluster of strange, mastless boats. They huddle together for mutual support like the oddball branch of a family at a wedding, shunned by their elegant, affluent cousins. In the darkness it is just possible to make out their unconventional livery of gaudy colors and loud patternsone painted with huge multicolored polka dots, another with the black-and-white splotches of a Friesian cow, others in green, or orange, or hot pink.

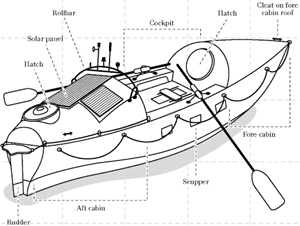

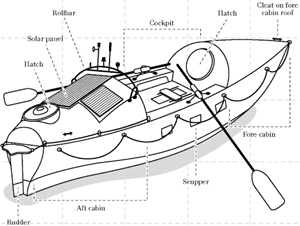

These boats do not appear to yearn for the open ocean as their masted relatives do. In fact, they appear barely seaworthy. They have no sails and no engine; their only means of propulsion is by oar, powered by human muscle. And one of them, the Sedna Solo, belongs to me.

It is the evening of Tuesday, November 29, 2005, the night before the start of the Atlantic Rowing Race, and I am sitting cross-legged on the floor of Sednas tiny cabin, feeling her bump against the pontoon on one side and another rowboat on the other. My ears strain against the howl of the wind for any sounds of scraping or chafing against the structure of my precious craft, and I pop my head out of the hatch every few minutes, into the darkness of the blustery night, to make sure Sednas fragile hull is not suffering damage.

The next day, twenty-six crews will set out to row three thousand miles across the Atlantic Ocean, from the Canary Islands, a few miles from the west coast of Africa, to Antigua in the Caribbean. They will make no landfall on the way, nor will they be resupplied. Every crew has to be entirely self-sufficient for the duration of the crossing.

The race organizers describe this as The Worlds Toughest Rowing Race, and in a modern world where superlatives are losing their impact, in this case the superlative is no exaggeration. Many previous attempts have foundered due to storms, breakages, injury, psychological problems, and catastrophic capsizes. Some ocean rowers have even paid the ultimate price. The pages of statistics on the website of the Ocean Rowing Society include a short but poignant list of names, titled Lost at Sea.

What reward awaits the winner? Nothing but a cheap medal and the knowledge that they have done something out of the ordinary.

Unsurprisingly, ocean rowing is not a majority sport. Since records began, fewer than three hundred people have rowed across the Atlantic, with most of them crossing in crews of two, although there have also been a few crews of four and, out there at the lunatic fringe of this most lunatic of sports, a tiny minority of people who chose to go it alone, adding the psychological challenge of solitude to the already formidable physical, technical, financial, and logistical challenges of rowing an ocean.

For reasons that make perfect sense to me, but to few of my friends and family, I have chosen to try to join this obscure tribe of individualists. I will be the only solo female entrant in this years Atlantic Rowing Race, and the first solo woman ever to compete in the event since it was first held in 1997. Five other women have rowed solo across the Atlantic, but those have all been independent expeditionsno woman has before pitted herself against other crews.

I ponder on this sobering fact as I sit in my cabin, rocking gently with the movement of the boat as the strong wind ruffles the usually calm waters of the sheltered marina. From the moment, fourteen months ago, when I first decided that I was going to do this, I have thought of little else. And yet, have I really thought about it at all? I have thought about what equipment I need, what food to bring, what course to navigatebut I still really have no idea what I am letting myself in for. There is nothing in my previous life that has prepared me for the reality of spending between fifty and one hundred and twenty days alone on the ocean. I know very little about what lies ahead. Until the race begins, my immediate future is simply unknowable.

In case you have formed the impression that I am some kind of athlete, adventurer, or adrenaline junkie, I should make clear at the outset my near total lack of qualifications for this undertaking.

First, I am not naturally sporty. If there is such a thing as a runners high, then it has so far eluded me. I get a quicker, easier high from a chocolate chip cookie than I do from a twenty-mile run and I only took up rowing in college so I could eat more without putting on weight. If you were to pass me in the street, you would not take me for an athlete. Most rowers are tall and powerfully built. I am neither. I am just under five-foot-four, with an unfortunate tendency to tubbiness.

I am also not naturally adventurous. I had spent most of my adult life working in an officeeleven years as a project manager in the information technology industrybefore deciding at age thirty-six to reinvent myself as an adventurer.