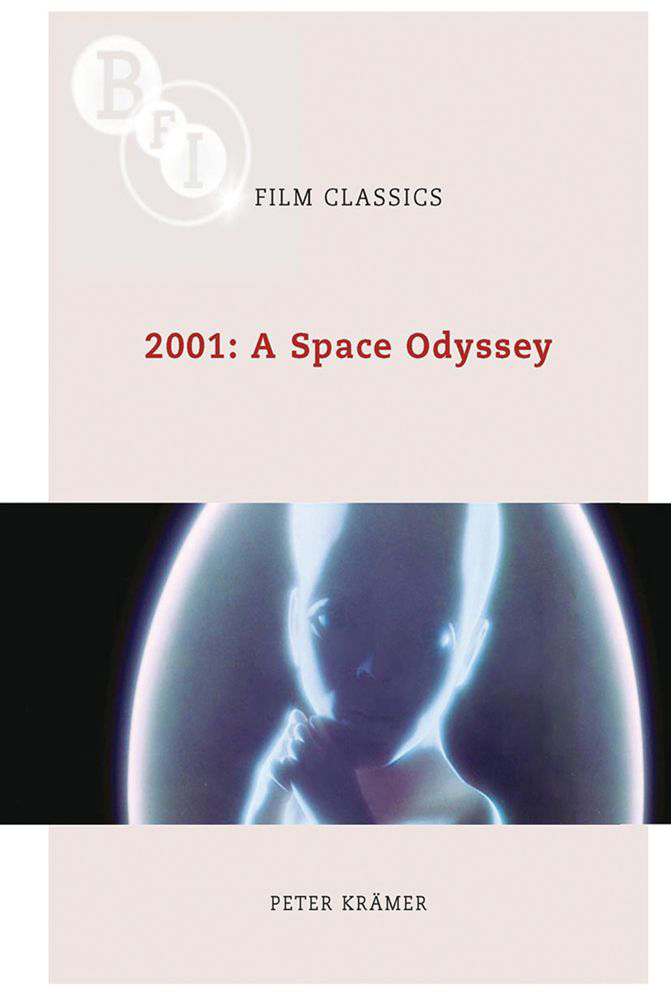

Krämer Peter - 2001: a Space Odyssey

Here you can read online Krämer Peter - 2001: a Space Odyssey full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: BFI Publishing, genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:2001: a Space Odyssey

- Author:

- Publisher:BFI Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

2001: a Space Odyssey: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "2001: a Space Odyssey" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

2001: a Space Odyssey — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "2001: a Space Odyssey" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visit https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

Contents

The first edition of this book was published in 2010. My BFI Film Classic on Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned toStop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) was published four years later.Dr. Strangelove and 2001 offer different visions of humanity's future, one deeply pessimistic in its focus on human compulsions, the other much more optimistic in its emphasis on human potential.

Amid many events celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of its original release, 2001 returned to cinemas in 2018, and Dr. Strangelove was reissued in 2019, coinciding with its fifty-fifth anniversary. The anniversaries and re-releases of these two classic films have given us an opportunity to consider their relevance for the world today.

Although it may not be terribly helpful to apply the adjective Strangelovian to Donald Trump (or Kim Jong-un),

At the same time, in a painful irony, it has long been obvious that human activities are responsible for the rise in global temperatures, which is already costing many lives and, unless drastic action is taken, is almost certainly going to have utterly catastrophic consequences in the not too distant future, perhaps destroying the very basis of complex societies. Among many other destructive developments, ever larger land areas will turn into deserts that cannot sustain much life.

In this context, the prehistoric scenes of 2001 depicting a band of hominids struggling for survival in an inhospitable environment have deeply disturbing resonances, especially when viewed with the title of the first chapter of Arthur C. Clarke's novel (The Road to Extinction) and its opening sentence in mind: The drought had lasted now for ten million years. Could the opening sequence of 2001 turn out to be a distorted vision of a post-historic landscape in a future in which runaway climate change has long destroyed humanity, leaving only small groups of humanlike beings slowly moving towards extinction?

This would indeed be a terrifying prospect, as is the lifeless surface of the earth (billions of people and animals wiped out by a radioactive shroud enveloping the globe) and the populated underground world envisioned by Dr. Strangelove at the end of the film named after him. Revealing himself as an unreconstructed Nazi (Mein Fhrer, I can walk! are his, and the films, last spoken words), he entices both the American leadership and the Soviet ambassador with his plan for a mineshaft society ruled by male elites, who are in charge of carefully selected underlings and breed prodigiously with fertile young women, all the while busily preparing for the next war.

Both Dr. Strangelove and 2001 focus on the uses and abuses of male power and technology. In 2001, the very origins of humanity are traced back to the moment when, under the influence of the mysterious monolith, Moonwatcher learns how to use a phallic bone as a weapon, and soon thereafter kills animals for food and the leader of a rival band for control of the local waterhole. In Dr. Strangelove the decision of an American general programmatically named Jack D. Ripper to launch an unauthorised nuclear bomber attack on the Soviet Union is initially traced back to his conviction that the Soviets have taken control of the American water supply, thus being able to contaminate his precious bodily fluids. Ripper then admits that this idea is in fact derived from his fear of women who, he claims, intend to extract his life essence through sexual intercourse. What is more, his attack on the Soviet Union finally succeeds when one of the bomber pilots enthusiastically rides a phallic hydrogen bomb to the ground, where its orgasmic explosion triggers a Soviet doomsday device.

Having examined the extensive literature on the nuclear stalemate between the United States and the Soviet Union, during the making of Dr. Strangelove Kubrick concluded that there could never be a technical or diplomatic solution, although a profound moral change of attitudes in men and nations might yet prevent disaster: The only defense is the mind of man, and I don't think he has even begun to face the problem. and an unsexed foetus, no longer dependent on the use of tools, floating in space in the vicinity of Mother Earth in 2001. For different viewers, this ending may well have a range of concrete philosophical, spiritual, even political resonances, yet its imagery is primal, archetypal, universal.

Clarke's novel ends differently, the Star-Child being identified not just as male but, more specifically, as another version of Moonwatcher, another master of the world who is not quite sure what to do next starting with the detonation of nuclear weapons orbiting the globe. However this action is interpreted (as the removal of a threat to humanity or its wholesale destruction to allow for a fresh start), the novel's ending circles back to the male deployment of weapons which, at the beginning of the novel, gave rise to humanity in the first place. This circularity is not so different from the way in which the ending of Dr. Strangelove marks the start of yet another arms race, this time underground, following the same military logic that has led to catastrophe on the earth's surface.

By comparison, in Kubrick's 2001 the images of the Star-Child and the earth, accompanied by Thus Spake Zarathustra, ultimately circle back to the first use of this musical piece in the film's credit sequence, which initially shows the moon, traditionally associated with female fertility, and then the beginning of a new day, the earth rising above the moon and the sun above the earth. Is it going too far to suggest that the imagery of these combined celestial bodies is evocative of a baby bump and a breast, the credits sequence thus pointing directly to the later birth of the Star-Child? Although Kubrick never spoke about this, with regards to Dr. Strangelove he was happy to point out the sexual framework from intromission to the last spasm underpinning that film's story.

Be that as it may, the final sequence of 2001 depicts, and celebrates, the birth of the Star-Child and its return to Mother Earth. By focusing on a foetus, the sequence emphasises the human capacity to develop in countless different ways, and the inclusion of the earth highlights its crucial importance for all human life. When the Star- Child finally turns towards the camera, staring out from the screen into the space we inhabit while staring at the screen, it seems that the Star-Child and the viewers are mirror images of each other.

The news about climate change is not good, and there are many reasons to believe that global disaster may be unavoidable now, but it is difficult to accept this. Would such acceptance not be completely paralysing? And yet, humanity lived for decades in the shadow of likely nuclear war, and large percentages of the population were, as surveys have shown, fully aware of the peril. Rather than being marred by all-encompassing despair, these decades, especially the 1960s and 1970s, were characterised by many developments not least the rise of the modern environmental movement which made the world a better place. It is high time for us to acknowledge the likelihood of a climate catastrophe, placing our trust in human potential. After all, we are the Star-Child, at home on Earth, at one with Mother Nature!

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «2001: a Space Odyssey»

Look at similar books to 2001: a Space Odyssey. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book 2001: a Space Odyssey and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.