.jpg)

.jpg)

CONTENTS

None of the kids who surrounded Natalie were more than fifteen. They were dressed in standard, tattered clothes, and nothing but the feral light in their eyes revealed their intent. One of them, a little taller than the others, was the first to speak. Where you going, lady?

Home, Natalie said, hoping her panic did not color her voice...

We got some questions to ask you, said another. You answer them right and well leave you alone.

You got any kids lady? said a new voice, one that cracked with adolescent change.

My son died. Natalie had not meant to say it aloud.

Alot of kids are dying, lady, the apparent leader said, without sympathy. When Natalie did not answer, he said it again. Lots of kids are dying, lady. He started to clap slowly. Lots of kids are dying, lady. Lots of kids are dying, lady. Lots of kids are dying, lady.

The others took it up, clapping or snapping their fingers, their walks bouncing with the rhythm. Some of them laughed at Natalies protesting, No.

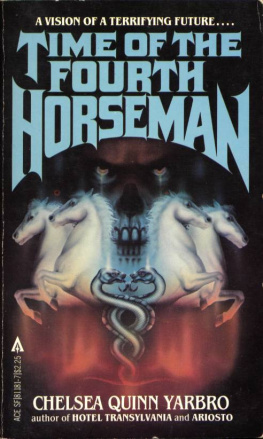

TIME OF THE FOURTH HORSEMAN

.jpg)

.jpg)

TIME OF THE FOURTH HORSEMAN

Copyright 1976 by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without permission in writing from the publisher.

All characters in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

An ACE Book

This ACE printing: November 1981

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in U.S.A.

This is for my friend

Tom Scortia

for his

in

as

and per

sistence

CHAPTER 1

FROM THE FIRST SIGHT of the boy, something felt wrong. Natalie bent over him while Gil read off the results of his pulse, temperature, blood pressure, hemoglobin, respiration and the others as they were displayed on the vital signs unit.

What is it, Nat? Gil asked as he caught the quick frown between her sandy brows.

She waved him away, a distraction. Her concentration was riveted on the boy. How old was he? Perhaps seven, maybe as much as nine and small for his age. His skin was parched and his eyes had the glaze of fever. Exposure she had read on his admit workup. Malnutrition.

You know, these kids are really sad, Gil observed as he studied the patient. This one makes an even dozen for this floor.

A dozen? Natalie had been off work for a week and this chance remark sharpened her fear.

Unhunn. Most of them were brought in while you were gone. They had a couple in the quarantine unit on the eighth floor while you were gone. County General is hardest hit, but theyre always short of beds and they get the runaways up there. I heard they picked up over a dozen starvation cases last week.

Starvation? Like this boy? She schooled her voice to betray none of the alarm she felt. She did not trust herself to look at Gil.

I guess its all the same sort of thing. The Patrol finds them and the ambulance service picks them up. Gil had been riding in the ambulance more often than not, with the current shortage of paramedics. Handys been after the Supervisors to do something about it.

Has it done any good? she asked perfunctor-ily, knowing the hospitals were not high on the Supervisorslist of priorities.

The young, abandoned children were bright in Gils mind. He had seen a lot of them, too many. No. No good.

Natalie shifted her balance minutely, studying the display board for the clue she knew was there. All her instincts told her that she was close to the enemy she and the child were fighting together. Hoping to learn more, she said to Gil, On the way in, did he say anything? Any complaints? Any unusual symptoms?

Just the usual.

The usual. Be specific, she snapped.

Gil smiled, because he liked Natalie when she got mad. It was the only time he felt he had the advantage with her. Yes, Sherlock, he did complain. He kept saying he was sore.

Where? Throat? Chest? Kidneys? Hands? Head?

Gil took a deep breath. It sounded more like general muscle aches, the all-over kind. Hed been huddled up for three hours when we brought him in. Hed been under the big viaduct north of here, on Route 5. He was badly chilled, too.

Headache?

Oh, I guess so. I didnt ask. Gil admitted to himself that he didnt want to ask. By the time they had brought that boy in, he had been working nineteen hours and was groggy. He still felt the fatigue as an undercurrent, even after getting a pick-me-up at the pharmacy.

I mean at the back of his head, that kind of ache?

I dont know.

The last question was really unnecessary, and Natalie knew it. The answer had clicked as she watched the boy. He had polio.

And that was impossible.

She felt dazed as she spoke. Have the standard tests run on him, will you? She was forcing herself to proceed as if there were nothing out of the ordinary about the case, just another abandoned child in the midst of many. Get me the results as soon as possible.

We ran through the basics on the ambulance console. The printout should be processed by now. Call Pathology.

She reached for the screen control, then hesitated.

Gil gave her a quizzical smile. You onto something, Sherlock?

She retreated into her most professional manner. Oh, probably not, but it never hurts to check. She was afraid she lied badly, but Gil didnt notice. I havent seen what the labs got out of the specimens yet, or the total arrival evaluation. I want to be on the safe side. As she spoke she wondered how the boy could have polio. Vaccination had wiped out polio over twenty years ago.

Laughing gently, Gil said, If youre on your way to the lab, I think Marks still there. If you need an excuse to see him.

Found out. She accepted his teasing, eager to fall back on this excuse. I never see him at home: we arent on the same shifts.

That bad? Gil asked, the teasing gone from his voice.

He keeps peculiar hours, Natalie said, wishing that she could change the subject.

I cant sympathize, Nat, Gil burst out harshly. You know what I think of Mark. Hes a high-handed despot ...

Before their argument could break out in earnest, the boy on the table moaned and his hands moved fitfully on the sheet like curled leaves in a slow wind. His face was waxen now. He mumbled a few words, then was silent.

What is it? What is it? Cant you tell me? she whispered fiercely over the child. She searched his face intently, hoping to find confirmation or denial of his disease. She wanted to be wrong.

You are spooked by this one, arent you, Nat?

A cold finger of fear slid down her spine. Why, no, not really, she said, hoping to dismiss the whole question. You know how mothers are. Philip was down with a cold last week and of course I read everything into it. Im suffering from maternal hangover, I guess, because I cant identify this bug.

Next page

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)