Contents

Guide

Copyright 2020 by Timbuktu Labs, Inc.

Rebel Girls supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book, and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting indie creators as well as allowing Rebel Girls to publish books for rebel girls wherever they may be.

Timbuktu Labs and Rebel Girls are registered trademarks.

Our books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sale promotions, premiums, fundraising, and educational needs.

For details, write to sales@rebelgirls.co

Editorial Director: Elena Favilli

Art Director: Giulia Flamini

Text: Corinne Purtill

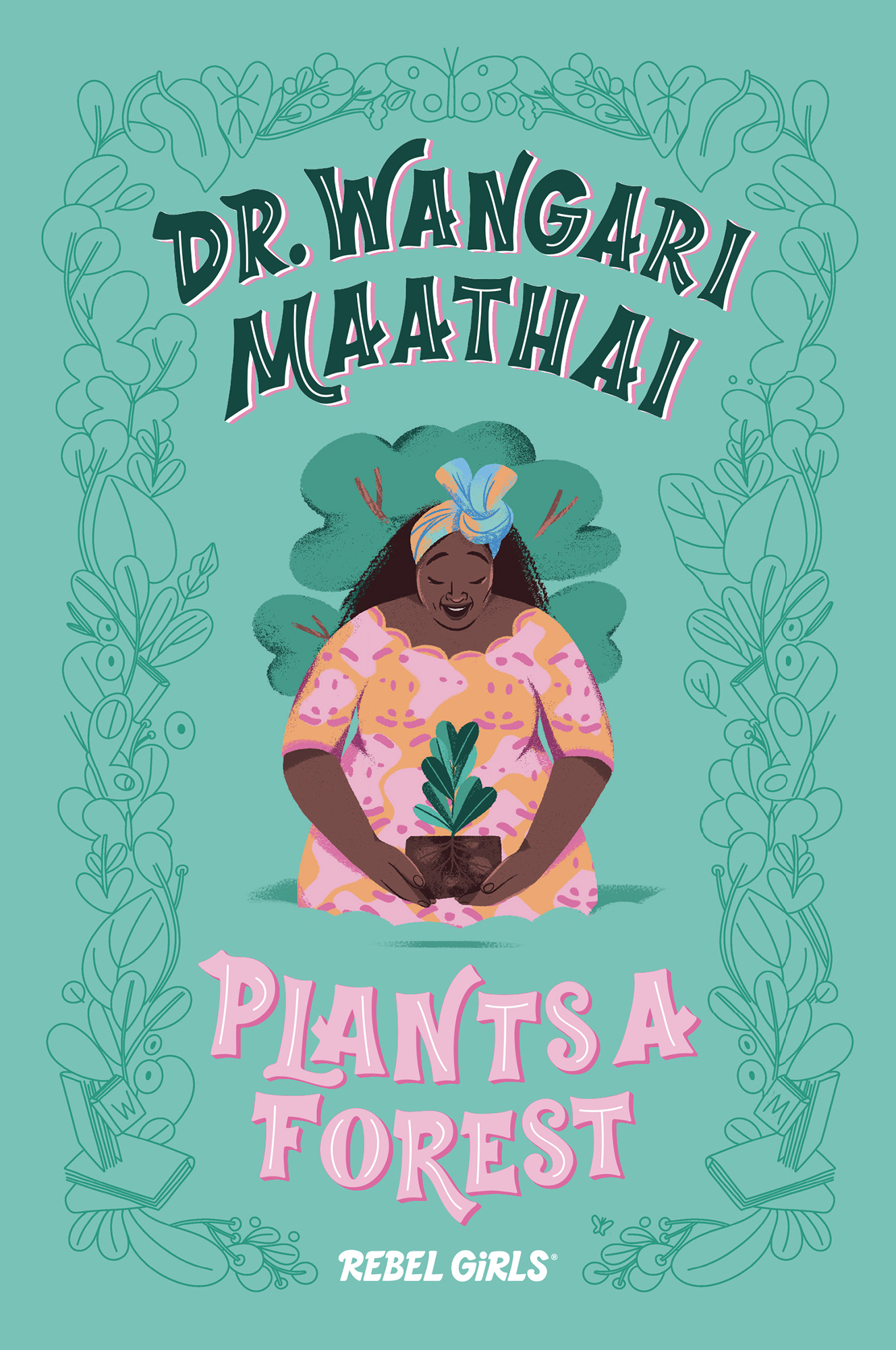

Cover and Illustrations: Eugenia Mello

Cover Lettering: Cesar Yannarella

Graphic design: Annalisa Ventura

This is a work of historical fiction. We have tried to be as accurate as possible, but names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents may have been changed to suit the needs of the story.

www.rebelgirls.co

ISBN 978-1-7333292-1-7

ISBN 978-1-7342641-6-6 (ebook)

MORE BOOKS FROM REBEL GIRLS

Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls

Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls 2

I Am a Rebel Girl: A Journal to Start Revolutions

Ada Lovelace Cracks the Code

Madam C. J. Walker Builds a Business

Junko Tabei Masters the Mountains

To the Rebel Girls of the world

Care for your beliefs as

if they were seeds,

then watch them grow.

Dr. Wangari Maathai

April 1, 1940-September 25, 2011

Kenya

CHAPTER ONE

I n the central highlands of Kenya, there grew a mugumo treea tall wild fig with bark as gray and gnarled as an elephants hide.

Nearby was a stream that bubbled up straight from the earth. And thats where, in 1947, seven-year-old Wangari Muta sat under the enormous leaves of an arrowroot plant and gazed into the waters at the reflection of her favorite tree.

Wangari scooped a delicious drink of cool water to her mouth with her hands. Satisfied, she looked up to where the great mugumos branches unfurled across the sky. She remembered the first time her mother had brought her here.

Do you see this tree, Wangari? her mother had said, shifting a basket to her hip and smoothing back the bright-red scarf around her hair. You must never take anything away from itnot even the dry wood for a fire.

Why, Mait?

The mugumo isnt a tree for people. Its a tree of God. We dont use it. We dont cut it. We dont burn it. They live for as long as they can, and when they are old enough, they fall down on their own.

Wangari had marveled, as she always did, at all the things her mother, Wanjir, knew about the way the world worked.

Looking back at the bottom of the shallow stream, she saw sparkling beads of black, white, and brown. They were smooth and perfect, just like the beads her grandmother wore. If she could pick them up, she thought maybe she could string them together into a necklace. She reached her hand into the water ever so gently. But as soon as the beads touched her skin, they broke apart.

What happened to them? she wondered, and not for the first time. Shed seen this before and was always surprised. Wangari knew that in a few weeks, the rest of the beads would be gone, too. Instead shed see tiny tadpoles that would dart from her hands when she tried to catch them. A few days later, she would find the tadpoles missing. Only the occasional frog would hop nearby. It seemed like magic.

She would have to ask her mother about this later. With questions swirling through her mind, Wangari gathered her basket, lifted it onto her back, and started for home.

Wangari lived in a village in Kenya called Ihithe. The path from the stream to her house led up a hill through a forest where elephants, antelopes, monkeys, and leopards roamed free. The soil felt sturdy under Wangaris bare feet, and she kept an eye out for other footprintsand paw prints, too.

If you are walking on the path and you see the leopards tail, be careful not to step on it, Mait had warned her.

But Wangari was not frightened. The word for leopard in her language, Kikuyu, was ngar. Wa-ngar meant belonging to the leopard. If she ever found one, Wangari was sure the beautiful cat would recognize her as one of its own.

As she approached the village, Wangari nodded politely at the women coming from the fields, their woven baskets brimming with roots and greens theyd plucked from the earth. The sun shone on her shoulders as she shouted and waved at other children who, like her, were carrying home their familys firewood and water.

Ahead of her on the dirt path, Wangari could see her mother carrying a basket of vegetables in her arms and her baby brother in a woven sling on her back. Her younger sisters toddled by her mothers skirts.

Her mother was the kindest person Wangari knew. She never yelled or said cross words. At the sight of her family, Wangari broke into a run, being careful not to spill the bouncing basket on her back. Together, they walked the rest of the way home.

Arrowroots! Thank you, Wangari, her mother said as she set the basket on the lush grass outside their home and handed the baby, Kamunya, to Wangari.

Wangari kissed her brothers chubby cheeks. He giggled and gurgled in return.

This part of the day was Wangaris favorite. She loved when her family gathered around the evening fire, the setting sun throwing golden light over the trees and rooftops. They roasted corn and potatoes, and the smell was wonderful. Ihithe was a village of small houses with mud walls and grass roofs. The Kikuyu, Wangaris people, always built their homes with the doors facing Mount Kenya. It was the place where God lived, Wanjir had explained to her children. As long as the mountain stood, it was a sign that everything would be all right.

Tell us a story! one of her sisters said.

Yes, Mait! Wangari echoed. She sat down with the baby in her lap, and the other children snuggled up next to her.

All right, her mother said. She picked up one of the knobbly roots and began to shave away the tough bark with her knife.

One day, a long, long time ago, there was a terrible fire in the forest.

In our forest, Mait? Wangari broke in.

Not too far from here, her mother said gently. It was an awful fire, with flames higher than the tallest giraffe. And it was hungry. It moved through the forest eating everything in its paththe trees, the flowers, everything.