CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

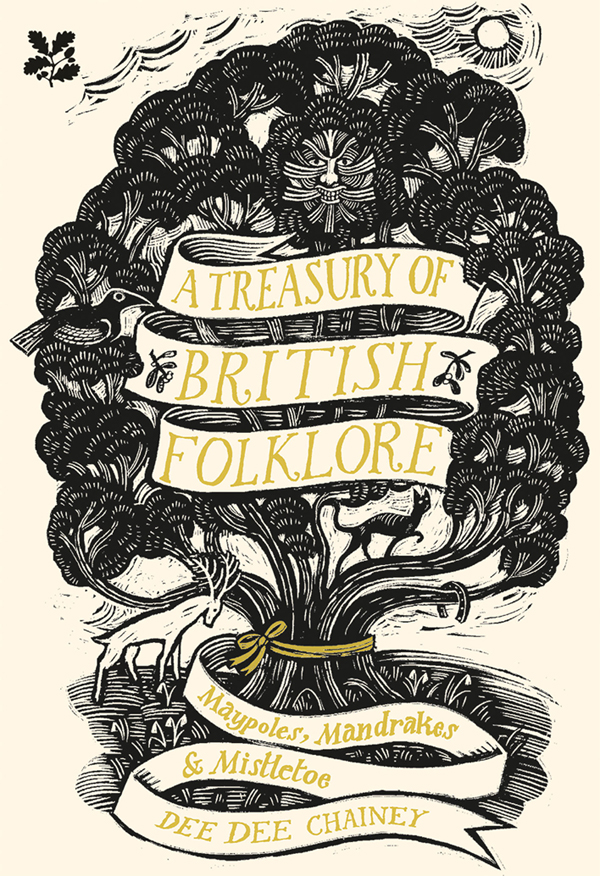

B ritains culture and traditions are steeped in legends filled with giants, heroes and heroines, centuries old and from various origins. These are Britains stories, and they belong to everyone who has ever lived here, or chosen to make Britain their home, and to every visitor who has marvelled at the legends of Britain and taken some of their magic back into the wider world. As we get older, we still sense the wonder of those tales we know from childhood. They whisper to us with every fleeting glimpse of what might just be a fairy in the woodlands, or a giant peering through a crevice in the rocks. Theyre our stories they grow with us and live on inside us. We tell them to our children and to their children, who will in turn breathe new life into these tales and traditions, carrying them forward in their own way.

There can be no definitive guide to the truth of British folklore. The only real truth is that folklore is the lore of the folk, passed on as a whisper, a tale or a tradition that goes on to become a thing that is shared. Folklore is made up of stories, songs, dances, customs and crafts that are passed from one person to another, and often from generation to generation. Folklore is the soul of a community: it lives, and changes, as it moves from the lips and mind of one person to the next. Folklore, including mythology and legends, comes from an oral culture that is in constant change, and there is no true version that is better or more real than the others. What we have of much early folklore is pieced together from old manuscripts, and not all of these survive. Those tales that were heard, recorded and written down often from memory and by hand were the versions of a particular storyteller, and a particular scribe. In the same way, we add our personal interpretation to folklore quite innocently: we retell the bits we love most, we emphasise the parts that strike a chord with us and we leave out things that seem irrelevant to us (even though others might find them fascinating).

In addition to personal interpretations, regional cultures in different parts of a country have an influence on its stories. Versions of a tale evolve as it moves across the land to different groups of people. Regions have their own local lore and traditions, distinct from their neighbours. The uses of folklore are many, and it is often used with intent. Its stories can underpin a sense of identity and belonging and reinforce the ideas people hold about themselves. It can be used as a cultural weapon, wielded against rival groups to prove how they are wrong, inferior or illegitimate. Folklore is alive and impossible to pin down, and can be dangerous. It presents people with a mirror to their own face, and can reveal the darker, more primal side of life. It is, after all, a thing written in the wind and the rushing waters.

Studying the shared myths and legends of the past show us that while empires may rise and fall, a sense of place and landscape can endure over thousands of years. These stories put our own lives in perspective. They reveal the vastness of time, and the reassurance that everyone, and perhaps every living being, is born, lives, may have fears and dreams, and eventually returns to the soil. In this way folklore is comforting, reminding us always to look at the wonder in the world. Folk tales and legends let us step outside of normal life for a little while, to think about something wonderful and magical, something other than our everyday worries. These tales offer the hope of heroes and gods, and the often the promise that in tales at least good will triumph over evil.

There are great swathes of folklore from the countries of Britain and Ireland going back thousands of years; too much to include in a small book such as this. Instead, the book features examples that illustrate the vastness of British folklore as a whole, with the aim of giving the flavour of the subject across a number of Britains regions. There is little room to dig deep into the intricacies of various debates that have raged for centuries on many of the topics, but I hope readers will enjoy the book for what it is a celebration of the folklore of a nation, in all its wondrous complexity and diversity, and an invitation to understand more about humans and the cultures they create.

1

OUR SUN AND

SEASONS THE

FOLKLORIC YEAR

T hrough all times and in all places people have conjured festivals to honour the changing of the seasons, the rising and setting of the sun, or the spinning of the stars. Each region has its own ways of marking the turning of the world, even if the importance of the darkening year and browning of the fields is a nostalgic memory of yesteryear for many. Its difficult to experience the changing landscape from our homes in built-up city areas. Even so, the turning of the world still lingers at the edges of our modern culture, in the crevices of our imaginations and in the corners of our traditions. This is what connects us with our animistic and animalistic past.

As people have done for centuries, we still look up to the sky, marvelling at the burning grandeur of the Sun, and the gentle beauty of the Moon, and folklore reflects our continuing wonder. In Scotland its seen as very good luck to always move sunwise in the same direction as the sun moves across the sky while moving widdershins, or against the Sun, is associated with bad luck and evil. It is, apparently, very bad luck to point at the sun at any time, and its often thought of as bad luck to see the moon through tree branches. For the antiquarians and folklorists of the past, the ancients were said to have many practices and observances surrounding the heavens. More recently, archaeologists have mapped out extraordinary solar and lunar alignments at ancient stones, from Lands End to John OGroats. We can imagine people of times long gone, watching the shadows trace across the land and solemnly taking measurements of the Suns rays, in order to build great megaliths and stone circles that marked special occasions in the year one such is Castlerigg in Cumbria, one of the earliest stone circles in Britain, dating from around 3000BC. Until the late eighteenth century in Britain, when artificial light through gas began to be developed, the period of darkness between the sun and the sky that is, between daybreak and sunrise was seen as a magical time, particularly potent for incantations and the best time for performing exorcisms. Just like us, in the Middle Ages people looked up to the night skies and saw the Man in the Moon. For them he was a rustic, or country dweller, bound in rags and carrying a faggot (or bundle) of sticks. Weighed down by his burden, both physically and symbolically, he was seen as a moral lesson on how stealing never profits.

As each new day dawns, marking the Suns travel, the named individual days of the week have come to have special significance in different places. Getting rid of the floor sweepings in Ireland on a Monday is said also to get rid of your luck for the week to come, while a sneeze on a Wednesday in Hertfordshire means a letter is coming. To begin anything on a Friday, from a journey to a business deal, is regarded as bad luck in Devon. In Norfolk, rain on Sunday morning apparently means rain all week.