Introduction

T his book is not intended to be a serious technical treatise on clocks and watches, although there are some serious, highly technical clocks and watches within its pages. Neither is it a scholarly, philosophical disquisition on the nature of time (Ill leave that to the really clever people); nor, finally, should it be taken in any way as a definitive account of the millennia man has spent trying to tame time a task as Sisyphean as it is Canute-like.

If the above paragraph has not dissuaded you from continuing to read, I suggest that you treat this book as you would a collection of very loosely linked short stories. Each chapter can be taken, and I hope enjoyed, on its own, as a discrete narrative; but also read in sequence, strung together like lambent pearls or dazzling precious stones, each one enhancing its neighbours to create a glittering jewel that is more than the sum of its parts. Or, at least, that is the idea I only wish my writing were worthy of the extravagant simile.

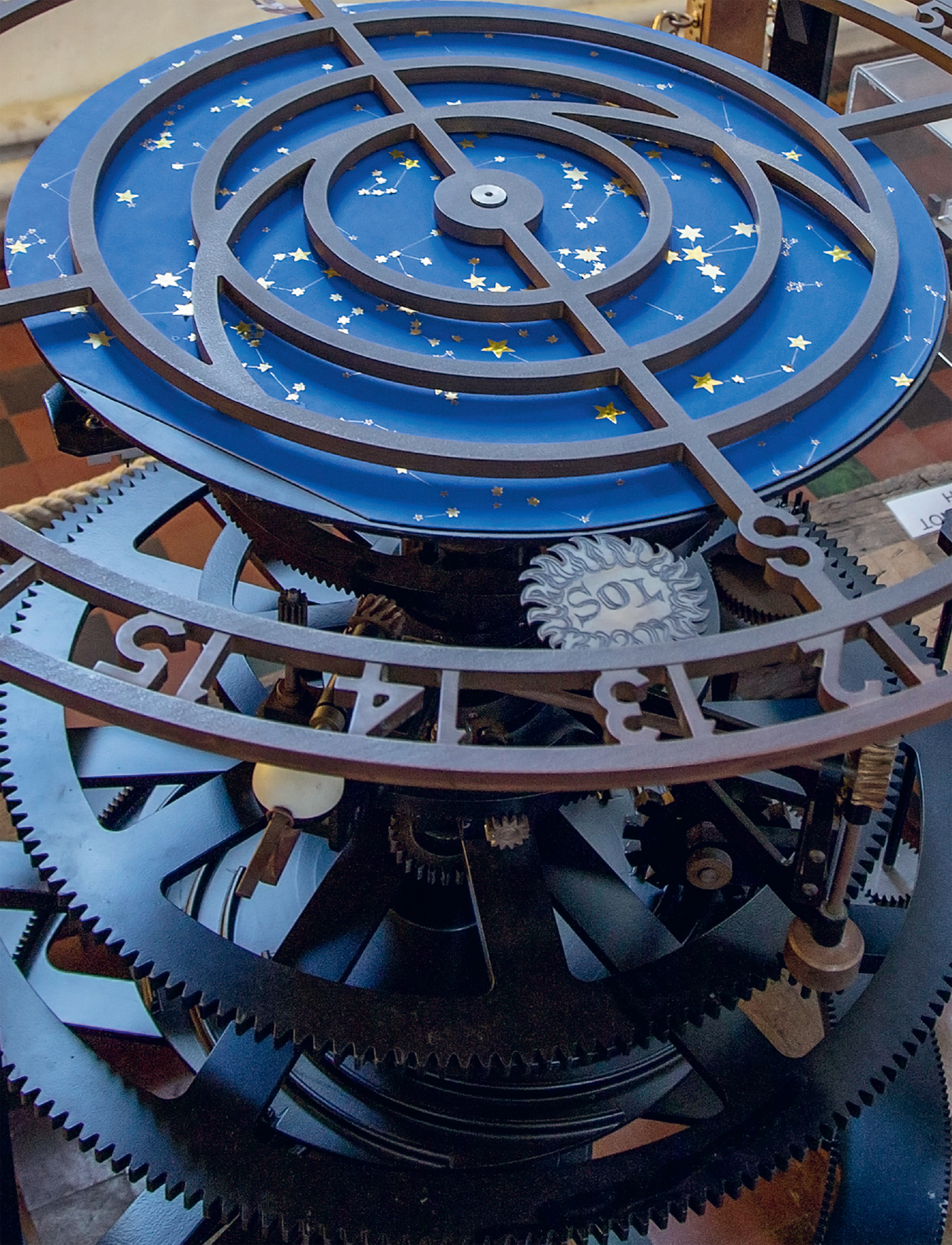

What is in no doubt is that the following selection of twenty-eight timepieces have all, in their way, contributed to history, and will take us on a journey from Mesolithic Scotland to Belle poque Paris; from the bottom of the Mediterranean to the surface of the moon; from the court of Charlemagne to the cockpit of a Pan Am Boeing; from Jacobean London to eleventh-century China.

But, however disparate the stories may seem, they are linked by the thread of human ingenuity and, more often than not, beauty. A timepiece is often an object in which science and art meet, where the calculation of gearing ratios and the finer aspects of the goldsmiths talents assume equal importance. In my opinion, the perfect timepiece is one that intrigues the mind and delights the eye, and in this book you will meet examples that achieve one, the other, and often both.

An understanding of time is arguably what makes us human; it is unsurprising that we value it and the machines that calibrate it for us. Indeed, the very story of human civilisation can be told through our ever-developing concept of time and the instruments with which we have interpreted it.

In its infancy, mankind experienced time as literally heaven-sent. The Earths rotation on its axis provided the span of the day, and the period of the Earths elliptical 365.25-day (give or take) orbit of the sun provided what we call a year. Meanwhile, the moon supplied the observable phenomenon of its waxing and waning, a cycle that took approximately 29.5 days, on which we based the concept of a month. The problem, of course, was that the solar and lunar cycles did not quite coordinate. It is possible that primitive men were grappling with this inconvenience as early as 12,000 years ago.

The Roman emperor Trajan depicted as pharaoh, offering a water clock to the goddess Hathor. Relief of the Mammisi, Temple of Hathor, 8851 BCE, Dendera, Egypt.

The reconciling of the solar and lunar calendars would occupy mankind for millennia, and continues to do so today. Babylonian astronomers found that these two calendars coincided once every nineteen years, and it was the Greek astronomer Meton of Athens who lent his name to the calendar that was used by Ancient Greece until 46 BCE .

However, while neat, a nineteen-year cycle is long, and all the time men were becoming more accurate in their appreciation of time. In Ancient Babylon, the span of daylight was divided into twelve hours and depicted on sundials, while the Egyptians had learned to tell the time at night using the position of the stars. Our seconds and minutes the former the sixtieth part of the latter, itself a sixtieth part of a larger unit of time were derived from sexagesimal counting that became the dominant form of calculation in Mesopotamia around 5000 years ago.

Of course, minutes and seconds were an abstract concept, more mathematical than temporal, and derived from this system came the 360 degrees of longitude that divide the world. (As we will discover, longitude would reunite with the human quest for accuracy in the eighteenth century.) For centuries, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, theology and time remained tied in the most Gordian of philosophical knots.

Plaster cast of the oldest extant Clepsydra (now held in the Cairo Museum) the worlds first (surviving) accurate timepiece discovered at the temple of Karnak, dating from 1415 to 1380 BCE.

With the invention of the water clock in Pharaonic Egypt, a way of measuring time (by the amount of liquid that flows regularly from a vessel) had been found. Finally, man had wrested time from the celestial bodies, and slowly the practical application of this almost Promethean gift began. Of course, for the majority, accurate time was not a necessity; ask a medieval peasant the time and he would probably tell you what season it was. Nevertheless, by the early Middle Ages, a combination of water clocks and solar observations were governing activities as varied as the closure of city gates and prayer all signalled aurally by hand-rung bells.

No one knows who invented the mechanical clock, but its arrival in thirteenth-century Europe brought with it the Renaissance and, a little later, the period of European world domination known as the Age of Discovery. For Karl Marx, its importance was in no doubt: The clock is the first automatic machine applied to practical purposes, he wrote to Engels in 1863, and the whole theory of production of regular motion was developed on it. Even though abstract, time had become the ultimate economic object. For Marx, the factory clock had become a symbol of depersonalization and the commoditization of human effort.

The pursuit of time and efforts to capture it with machines has involved strong personalities and great characters who, through their stubborn perseverance, innate genius or sheer eccentricity, have written their names into the history of timekeeping: from prehistoric humans to astronauts, these pages tell a story of mankinds invention of time that begins with us looking at the moon and ends with us walking on it.

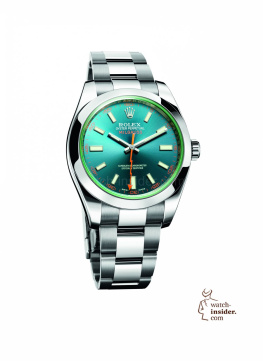

Those who surrender to the appeal of clocks and watches enter an endlessly engrossing world: a mechanical microcosm of components capable of the humble task of telling the time or the lofty one of predicting the movements of the stars. The fascination is the same for all whether Pharaoh, eighteenth-century French queen, twentieth-century tycoon, or, in a much more modest way, me, when I was growing up in the 1970s.

At that time, battery-powered watches were all the rage, and old mechanical watches could be had for pennies in junk shops and jumble sales. I wore them until they broke or until I found another I liked. They were everyday objects, and yet I felt they possessed a beauty that, when on my wrist, ever so slightly improved my experience of life. They also amazed me in the way that they compressed their untiring functionality into a space about the size of a coin. Their dials boasted about the number of jewels they contained, their automatic self-sufficiency, and their pride in being Swiss Made. While their case backs proclaimed their impregnability with a list of attributes: waterproof, shockproof, dustproof, anti-magnetic