Contents

Guide

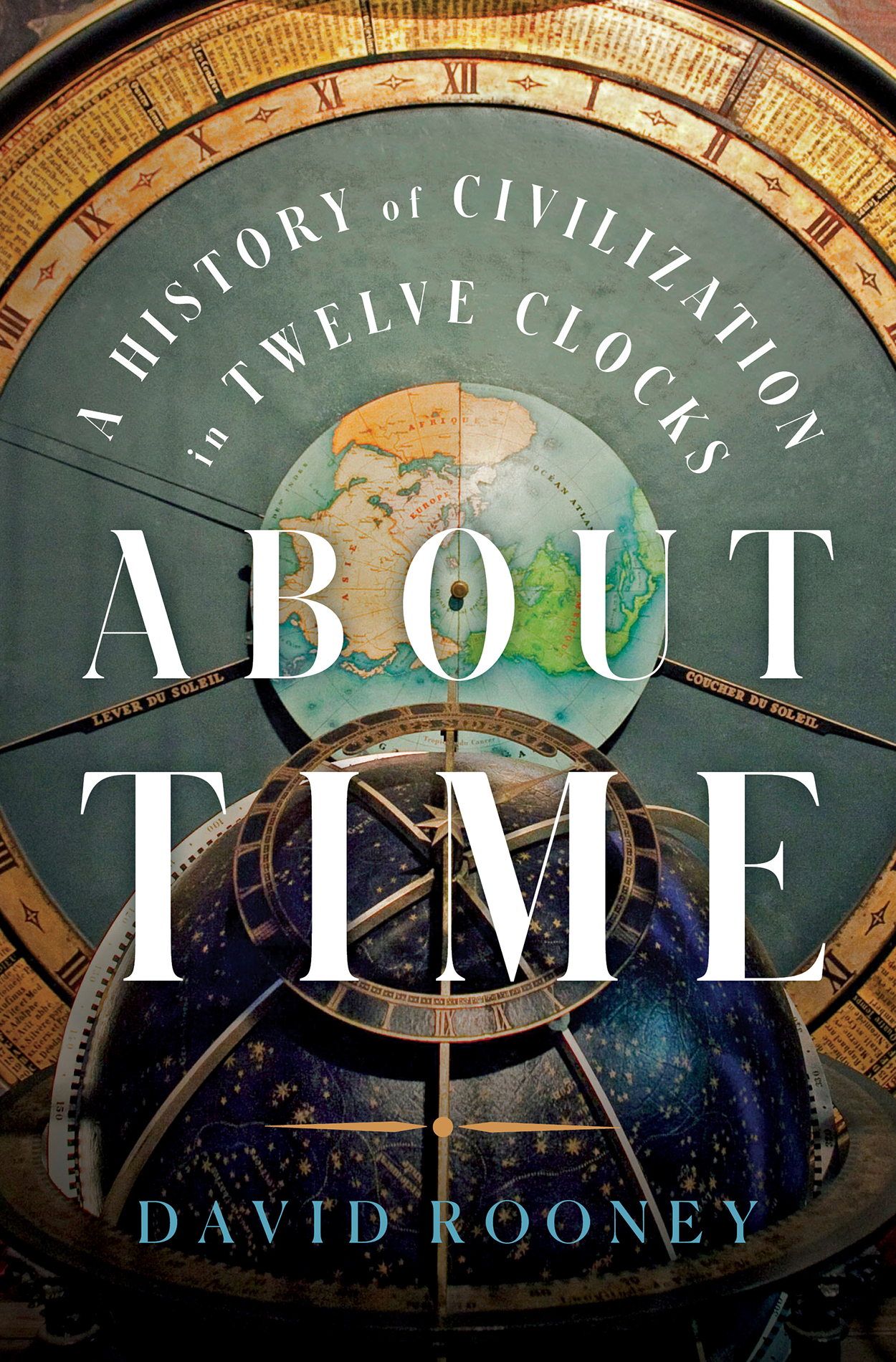

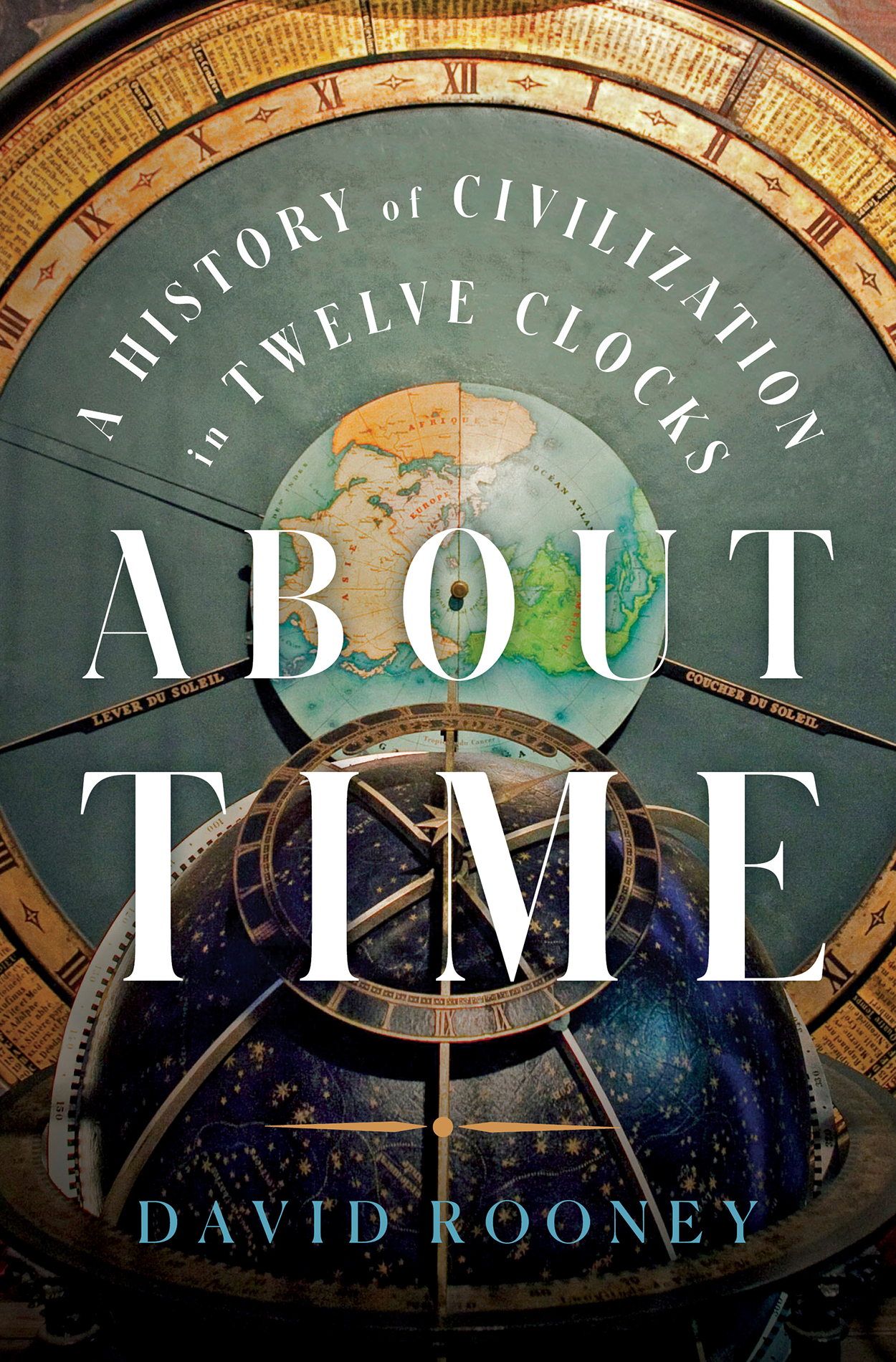

About

Time

A History of Civilization

in Twelve Clocks

DAVID ROONEY

Copyright 2021 by David Rooney

The credits on pp. 259260 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

First American Edition 2021

First published in Great Britain by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Books

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-0-393-86793-0

ISBN: 978-0-393-86794-7 (ebk.)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0

Contents

About

Time

I t is the early hours of a crisp Alaskan morning. Korean Air Lines Captain Chun Byung-in, First Officer Son Dong-hui and Flight Engineer Kim Eui-dong stride purposefully across the tarmac of Anchorage International Airport and climb into the cockpit of the Boeing 747 airliner that they are rostered to fly to Seouls Gimpo International Airport.

Flight KAL 007 has stopped off at Anchorage on its journey from New Yorks John F. Kennedy International Airport for servicing, refueling and a changeover of the flight and cabin crew. The Alaskan airport, on the northwest tip of North America, is, at this time, a common staging post for flights between the USA and eastern Asia. Much airspace over the communist countries of Asia and Europe is closed to foreign traffic, meaning longer routings for flights seeking to find a way through safe international corridors. But Chun, the pilot of the flight, knows the passage from Anchorage to Seoul like the back of his hand, having flown it for half a decade.

The first leg of flight KAL 007 has been uneventful for the 269 people on board, and weather conditions for the second leg are predicted to be good, with lower than average headwinds meaning the flight duration will be slightly reduced. In order to arrive at Seoul on time, the departure from Anchorage is therefore set back by half an hour. The final checks are completed and nothing seems out of the ordinary. A route is punched into the navigation computer that will take the aircraft safely around the outer edges of prohibited airspace, and the airports radar systems record flight KAL 007 in the air at 4 a.m., Alaska time. It has all the makings of an unremarkable flight.

The hours pass. Conversation among the flight crew is jovial and relaxed. At certain points during the flight, they contact ground controllers to report their position and weather, and to confirm plans. Breakfast is served to the passengers, just as normal.

But there is a problem with the aircrafts autopilot. What Chun, Son and Kim have not realized is that it has not been set up correctly, and throughout the course of the flight from Alaska they have strayed increasingly to the north of their intended route. It is the worst possible mistake they could have made. With no way to double-check their position, they have relied on their navigational equipment to direct the aircraft along the required route, but it has taken them directly into prohibited airspace over the Kamchatka Peninsula and the island of Sakhalin.

Five hours after the Boeing jet leaves Alaska, and unknown to the Korean flight crew, a Sukhoi Su-15 supersonic jet, piloted by Lieutenant Colonel Gennadi Osipovich, is scrambled to intercept the airliner. Osipovichs military commanders have recently spotted a US spy plane operating in the area, monitoring a missile test being carried out. This is a well-known Boeing RC-135 four-engine reconnaissance jet, similar in many ways to the Boeing 747 passenger jet but without the distinctive hump above the cockpit. Osipovich and his bosses are convinced the Korean Air Lines aircraft is another US spy plane.

Twenty minutes later, having reached the airliner with its oblivious crew and passengers, Osipovich fires a burst of warning shots from his cannon across the Boeings nose, but the shells cannot be seen by the Korean crew, who carry on chatting, unaware of the danger that is fast closing in on them. Six minutes after that, Osipovich launches two air-to-air missiles at the Korean airliner. One misses, but the other explodes at the Boeings tail, severing hydraulic control lines and inflicting significant structural damage. Shrapnel from the blast penetrates the airliners fuselage, causing the cabin to decompress. Though it has been mortally wounded, flight KAL 007 continues to fly onward as the crew struggles to regain control. Automated announcements on the public-address system begin to sound throughout the aircraft, thirty seconds after the missile strikes. Attention. Emergency descent. Put out your cigarette. This is an emergency descent. Oxygen masks drop from the ceilings in the cabin and cockpit and the PA system begins to shout, Put the mask over your nose and mouth and adjust the head band. Attention. Emergency descent.

The airliner continues to hurtle through the skies above the Sea of Japan. The passengers who remain conscious, while they do not know what hit them, or why, are in no doubt about the grave danger they face if the aircraft cannot be brought into an emergency landing. The crew continue to wrestle valiantly with the controls as they become less and less responsive. The airplane bucks and rolls as it is buffeted by winds and weather, having lost the aerodynamics needed for safe flight. Twelve minutes after the missile is fired, what limited control the pilots have of the jet is lost and, having plummeted down in a deadly spiral, flight KAL 007 slams into the ocean. The terror is finally over. It is the morning of September 1, 1983, and there are no survivors.

Overhead, a fleet of seven experimental US military satellites called Navstars is orbiting. Each satellite is the size of a family automobile and weighs just short of a ton. They are powered by a combination of solar cells and hydrazine rocket fuel, and the fleet has been launched, one by one, every few months since 1978. Between them, these satellites are carrying twenty-five high-precision clocks, built in California, as part of a navigational experiment called the Global Positioning System.

These clocks could have saved everyone on board flight KAL 007.

FOUR DAYS AFTER the Korean airliner was shot down by a Soviet missile, the US president, Ronald Reagan, made an emotional television address in which he described the tragedy as a massacre, a crime against humanity and an act of barbarism by the Soviet authorities, vowing to take steps to ensure it never happened again.

The experimental satellites flying above the aircraft as it plummeted down to Earth were the first in a constellation we know today as GPS, then being developed by the US military. Each GPS satellite carried three or four miniature atomic clocks, which beamed precise time signals to Earth, where people carrying GPS receivers could find their position to within tens of yards. Today, the GPS system involves around thirty-two satellites that are active at any one time, and the latest ones carry clocks far more reliable and accurate than the first ones, made in the mid-1970s.