Ghost Light on Graveyard Shoal

Elizabeth McDavid Jones

To Mr. Thomas Scheft, my seventh-grade English teacher, who was the first to tell me I would someday be an author

And to all the Mr. Schefts everywhere, those teachers par excellence who truly believe in their students

C ONTENTS

C HAPTER 1

S HIPWRECK !

Wednesday, May 8, 1895

Rhoda, wake up. The urgent whisper penetrated the thick mantle of sleep that blanketed Rhoda Midyettes mind. Her eyelids fluttered open to the sight of Mamas face above her, ashen in the glow of the porpoise-oil lamp, fashioned from a whelk shell, that Mama held. Rhoda could hear the shriek of the wind outsidethe noreaster that had threatened yesterdayand the first thought that jumped into her mind was that something had happened to Daddy.

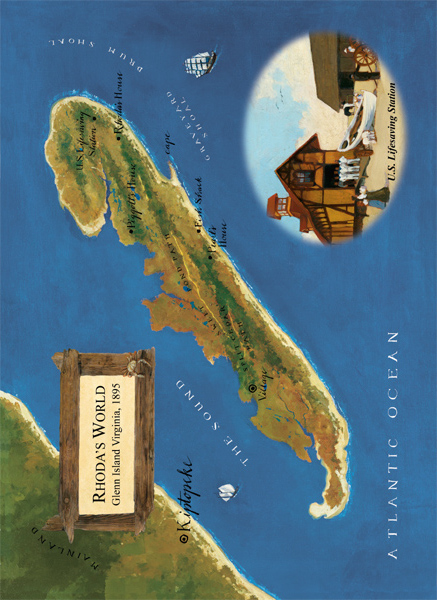

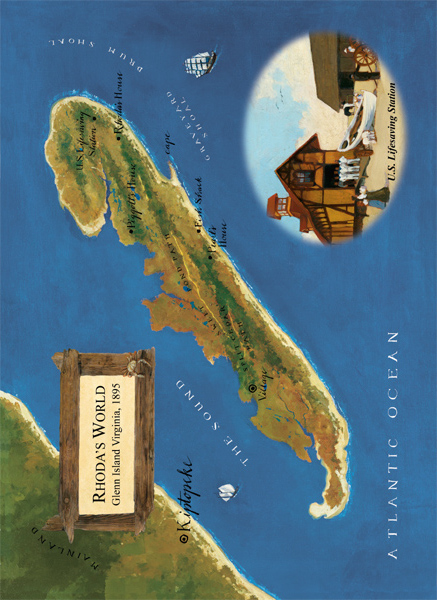

Daddys job as keeper of the U.S. Lifesaving Station here on Glenn Island put him in constant peril; it was his duty to lead rescue operations anytime a ship wrecked or foundered on the dangerous shoalsthe underwater sandbanksthat surrounded the island. Rhoda could think of no other reason why Mama would awaken her in the middle of a stormy night except to tell her that something had happened to him, something too terrible for the ears of her three little sisters, who were sound asleep in the big bed across the room.

Rhoda bolted upright in bed. Daddyis he ?

Mama placed a finger to her lips. Shhh, hes fine. But a schooner drove onto Drum Shoal last night in the storm, and your daddy and the other surfmen been working all night to try to get the crew off fore the ship goes to pieces in the surf. Harlan Swanson just came by to tell me the surfboats on its way in now with survivors, and theyre bound to be bad off, theyve been clinging to that wreck so long.

Harlan Swanson, the youngest and newest member of the lifesaving crew, had come to the island only eight months ago, when he was hired at the beginning of storm season in September. Since he was a bachelor and had no family on the island, Mama did his laundry and mending for him. In return, he did odd jobs for her on his day off. It was a help to Mama, since all during the long months of storm season, Daddy, like all the lifesavers, had to live at the station, visiting his family only one day a week. While Harlan was around, he always made time to talk to Rhoda and had fast become her favorite surfman.

Those poor sailorsll be scarcely conscious and half froze to death, Mama was saying. Theyll need tending. And your daddy and his men, too. Dry clothes and hot food, fast as we can get it ready.

Mama was the cook at the station, and Rhoda sometimes helped her in an emergency, though Mama had never before asked her to do so in the middle of the night. But now that Rhoda was twelve, Mama seemed to count on her more to help out, to take care of her sisters and tend the house while Mama worked at the station. Rhoda was proud that Mama considered her grown-up enough to handle such responsibility.

Quick now, up and dressed with you. We need to get to the station, Mama urged.

What about Margaret? And Pauline and Thelma? Should I get them up and dressed and tote them along?

Mama lifted the lamp to peer at the three little humps under the covers that were Rhodas sisters. The patchwork quilts rose and fell with the girls rhythmic breathing. Mama shook her head. Let em be. We should be back before they wake up. And if were not, Margaret can tend Pauline and Thelma. You did when you were nine. Hurry now. Mama set the lamp on Rhodas nightstand and tiptoed from the room.

It was true, Rhoda thought. She had done a lot more at Margarets age than her sister seemed to do now. But that was what came with being the oldest, according to Daddy. He expected more from Rhoda, he said, and she did her best to live up to his expectations, hard as it sometimes seemed.

Rhoda slid out from under the warm quilt and sucked in her breath at the assault of chill air on her flesh. How could it be this cold in May? Only a week ago, a southwesterly wind had brought temperatures so warm that Rhoda and her sisters had gone wading in the ocean. A few days ago, though, the wind had shifted and the temperatures plummeted, and it was back on with ribbed winter stockings and woolen sweaters.

But that was the way it was here on Virginias Eastern Shore, especially on the barrier islands like Glenn Island. The ever-changing, ever-blowing wind characterized the weather and shaped the lives of all the islanders, even the island itself, constantly shifting the landscape, erasing and rebuilding the giant sand dunes that bordered the ocean. To Rhoda, who had lived her entire life on the island, the wind had a personality as real as that of any of the islands inhabitants. And the noreaster was the orneriest of winds and the least predictable, often arriving in spring when the weather was just turning warm and blowing up sudden squalls that churned the waves to froth and tossed ships about like toys. Noreasters were some of the worst storms for shipwrecks.

She tried not to think about Daddy and the others in the surfboat now, being tossed about in those waves. Last year during a rescue in a blow like this, one of Daddys crew was washed from the surfboat and drowned. Ever since, the fear lingered in the back of Rhodas mind that the same thing might one day happen to Daddy.

Banishing such scary thoughts, Rhoda dressed quickly and slipped out into the front room, where Mama was waiting for her. Even here, behind the dunes and the sheltering live-oak grove where their house was nestled, gusts of wind shook the windows and seeped through the wood-slatted walls, raising goose bumps on Rhodas arms and legs. Mama had stoked the fire in the big cast-iron stove that stood in the middle of the room, and Rhoda wished she could stay here for a while and get warm. But Mama, dressed for the storm in Daddys old oilskin coat and broad-brimmed hat, called a souwester, was handing Rhoda her own raingear. Rhoda donned the oilskin that fell to just below her knees, barely covering her woolen dress, and put on her souwester. Then, with Mama carrying the big whale-oil lantern, they went out into the night.

The tops of the loblolly pines bent and swayed in the wind, and the branches of the live oaks rattled and roared. Rhoda held on to her hat to keep it from being swept off her head. She followed Mama along the twisting path that tunneled through the trees, though neither of them really needed the lantern. Rhoda had walked this path so many times, she could have done so with her eyes closed.

The woods soon gave way to wax myrtles and scrub holly, and then to the dunes, thick with salt-meadow hay and sea oats bent prostrate in the wind. At the top of the dune, the wind hit Rhoda full force, slinging sand and needles of rain like tiny spears into her face, snatching her breath and cutting through her clothes as if they were made of paper. She pulled her oilskin tighter against the knifing cold. She could only imagine how frozen Daddy and the surfmen must be, not to mention the poor sailors they were trying to save.

A faint pink light showed on the rim of the horizon, but the rest of the sky was a sooty gray. From the height of the dune, Rhoda could just make out the dark shape of the wrecked schooner, or what was left of ittwo masts with spars poking up like bones above the surf, lurching violently back and forth from the crash of the waves against it. The ship appeared to be grounded about a half-mile out from the station.