For Louise, Benjamin and Gabriel

and

in memory of Christian, Tracey and Alexandre Foures

You will pass through storms and heavy rains and at times you may suffer defeat. The essence of a creative life, however, is not to give up in the face of defeat, but to follow the rainbow that exists within your heart.

Daisaku Ikeda

Contents

YOU ARE ALONE. You have only seconds left to live. Not long enough, you may think, for the massive database of your life experience to reassemble itself into an order of merit. Time slows. Seconds stretch, hammered flat on the anvil of oblivion, reaching towards infinity.

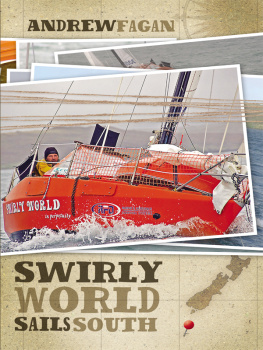

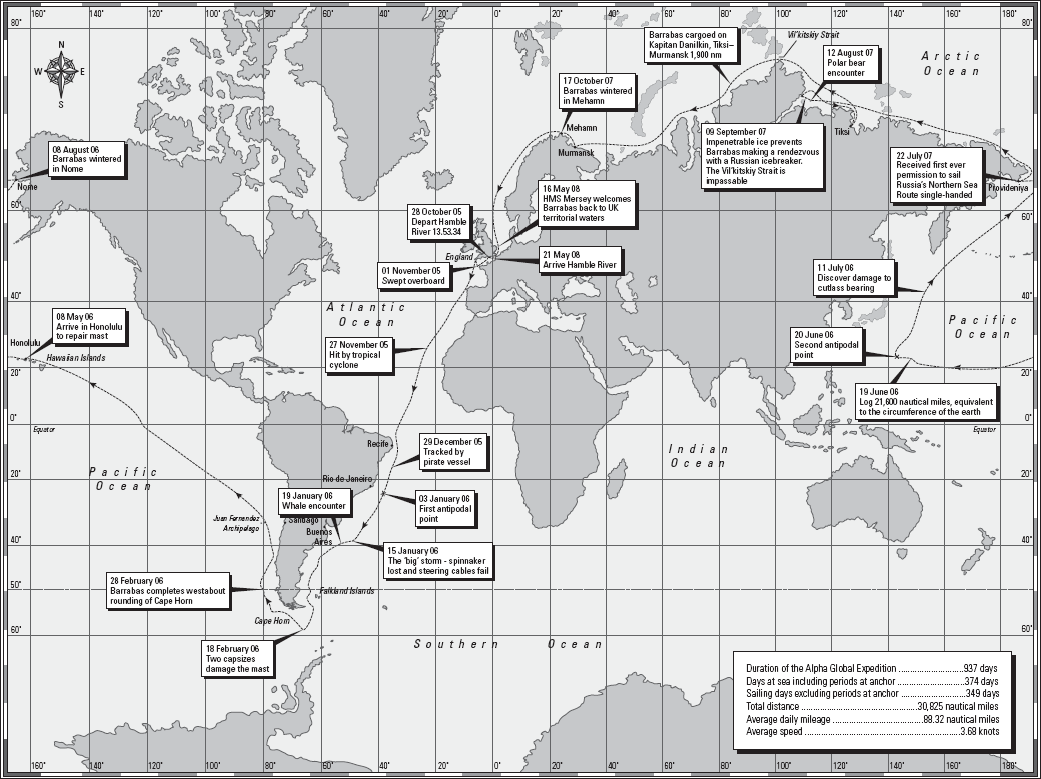

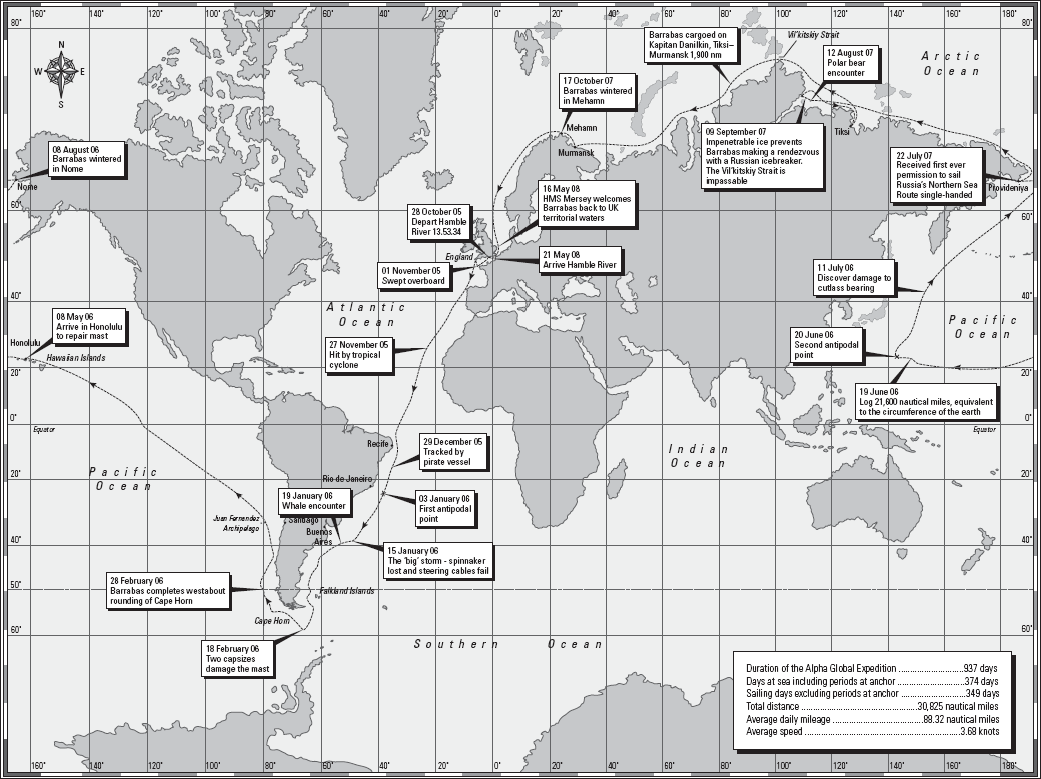

Alpha Global Expedition, Day 5

Tuesday 1st November 2005

49.09.5 North, 06.50.3 West Western Approaches, English Channel

Dawns grey light seeping in from the east makes little impression. Storms have raged through the night. The narrow confines of the English Channel heap the seas into marauding waves. Near hurricane-force winds screech through the rigging. I have been bashing into these gales for three days. Bad weather was predicted, but not to this extent, not at this severity.

Its been five days since I departed from the River Hamble on my quest to sail around the world. My route is planned to take me westabout Cape Horn, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean then over the top of Russia, through the North Polar region. For now, I am somewhere off the south coast of Cornwall. Relentless headwinds neutralise meaningful progress. Ive eaten little food and hardly slept. Seawater has fouled my freshwater tanks.

At 8am, the wind suddenly dies to 16 knots, a respite while the eye of the storm passes over. I take the opportunity to rig the storm jib and set up the Hydrovane self-steering gear: a wind vane attached to a servomechanism that connects to an auxiliary rudder via a shaft. The rudder is made of dense nylon but does not float. I tie a lanyard through the rudders carrying handle and make it fast to a strong point on the transom, a precaution in case the rudders securing pin fails. The lanyard is a 2-metre loop. I let it fall into the water and trail behind the boat.

Within five hours, the weather has gone berserk. Wind speeds reach 50 knots. One yacht 15 miles east of my position activates its emergency beacon and an air-sea rescue helicopter flies out to pick up the crew. I listen to the frantic radio exchanges. It is the first of three mayday calls I hear that morning.

The boat takes a wave bow on, riding high, her nose pointing skywards. She comes off the wave with a tremendous crash. A loud cracking sound ricochets from below and I think my yacht has split herself open. I duck down the companionway steps. I use both hands to prevent myself from pitching forward or being flung backward or hurled sideways. In the dim light below decks, I feel immediate relief. There is no water rushing in, drowning my boat. I go to the fore cabin. Eleven fuel cans weighing a combined 220kg have smashed through the storage cage. The stench of spilt diesel percolates the cabin. I rush back to the cockpit, gybe the boat, backing the sails against the rigging and then lash the wheel hard over in the opposite direction so that the sails and rudder are working against each other. This manoeuvre heaving-to stops the boat in the pounding seas.

I set about sorting out the mess. My first priority is to stow the fuel. I lash two cans alongside the ones already in the aft deck fuel cages, one either side. I make space for three more in the lazarette. There is space for the remaining six cans in the cockpit, forward of the wheel, which makes getting to and from the cabin awkward in the difficult conditions.

The necessity of maintaining a radar watch in the busy shipping lanes has confined me below decks for most of the time since dawn. I am safer below, and dry. In the early afternoon, I come on deck. My mission is simple and quick: to alter course 15, which means adjusting the self-steering vane. The control line is a continuous loop running from a cog on the Hydrovane to a small block clipped to the guardrail on the starboard side level with the cockpit. I plan to be on deck for 10 seconds, no more, sufficient to eyeball my horizons for shipping and tug on the self-steering control line. I am dressed in two T-shirts and a pair of longjohns as base layers, an all-in-one fleece-lined mid-layer, heavy-duty oilskins and sea boots. I am not wearing a lifejacket or a safety line.

For the moment, the large cuddy a tubular steel framework clad in sheets of tough transparent polycarbonate protects me from the elements. I clamber over the six fuel cans in the cockpit, scanning the forward horizon. A turbulent, cold, grey sea stretches away, lost in mist. I look sternwards. All clear. Now the adjustment. I step onto the starboard side deck. With my left hand, I reach towards the control line, bending at the waist, facing backwards. In that instant, a wave hits the boat on the port side, heeling her over at an acute angle. The starboard toe rail dips below the surface. Water rushes over my left boot.

I never see the wave that sweeps over the bow. Perhaps the seas have lifted the yacht and then she digs her bows into the water. Maybe a second wave has hit the boat on the starboard side in the confused cross chop. I will never know exactly what happened. There is no noise of water charging up behind me, or perhaps the wind has torn away the warning sound. My fingers never make it to the control line.

The impact when it comes is immensely powerful; a vice-like grip against the back of my left leg and the exposed part of my upper body leaning out past the protection of the cuddy. The water knocks me over and picks me up, my body flat, parallel to the deck and four feet above it then sweeps me over the guardrail. My arms flail, trying to propel me back on board, trying to grab a handhold. Through the foaming maelstrom of water, I see parts of the deck, the main block and the cockpit winches flit away to the right. Then I see the bare steel of the hull and through the green lens of sea the blue nameplate of the boat, white lettering spelling out B A R R A B A S. The water releases its hold and I plunge into the sea, completely submerged. When I break the surface, the nameplate is directly above my face. I am completely separated from the boat.

This is what goes through my mind:

Death is a certainty. Okay, this is it, aged 45.

I see my French friends, Christian and Tracey Foures and their 10-year-old son, Alexandre, all killed the previous year in the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami.

The angelic faces of my two boys, Benjamin and Gabriel, smile at me.

The startling green eyes of Louise, my ex-wife and expedition manager, twinkle with love or sympathy Im not sure which, perhaps both.

Drowning is too unbearable to contemplate. I will strip down to my base layer and let hypothermia claim my consciousness before the sea takes me down.

Despite the frigid water, I feel warm and irrationally calm. I surmise afterwards that in this moment of extreme danger, adrenalin flooding my system has shut down core functions and diverted blood to the muscles of my arms and legs, bringing warmth. My vision sharpens to the acuity of an eagle. Maybe the calm that I feel is part of this primeval fight/flight response or perhaps it is the simple realisation that the game of life is up. Maybe I even feel some measure of relief. I cannot be certain.