Thirteen years

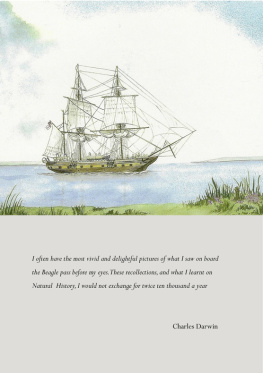

B oxing Day, 12.30 p.m., 26 December 2006. All the jobs were done. All the vital life-perpetuating objects were on board, myself included.

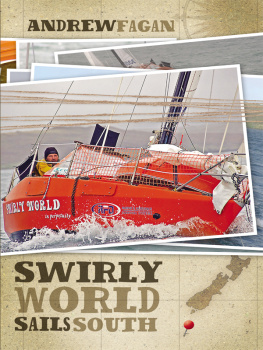

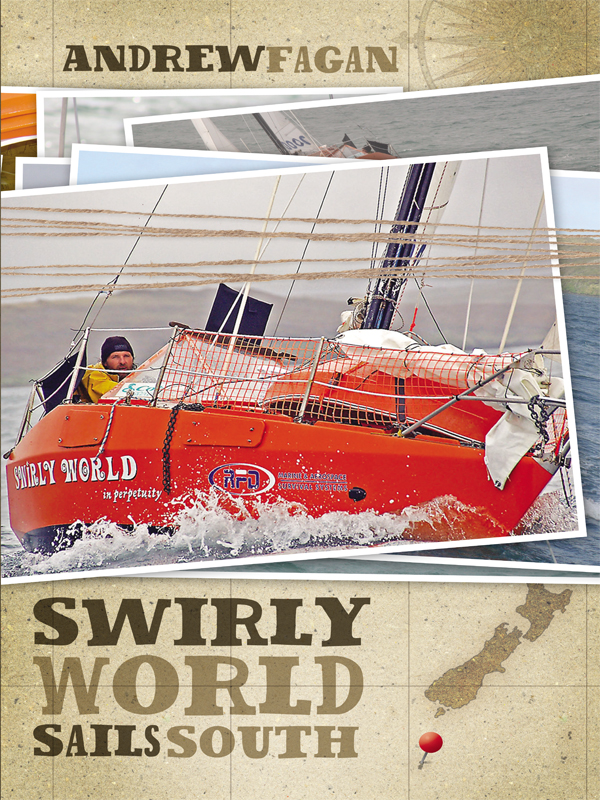

Swirly World had been rafted up alongside Ethel (an 1896 Logan ketch) in the Auckland Viaduct for a week while I slowly filled her up with food and water and other important things. It was finally time to go. A private departure free from the expectations of others had been planned in advance. We were off. Me and the boat, the boat and I. Karyn, Seth and Fabian waved goodbye. So did I.

A big push backwards (no reverse gear) got SW out enough from the wharf, then I rushed below and started the engine and we motored slowly out past the moored multi-million-dollar yachts and motorboats lining our pathway to the Viaduct exit. No point complicating things at this stage with sailing in such confined quarters; Id leave that for later.

Once outside the Viaduct and with more sailing elbow-room, a light westerly wind and well-timed outgoing tide were waiting for us. Boxing Day had brought out many other sailing boats, all departing Auckland harbour and heading for the Hauraki Gulf bays of recreation. We joined the procession.

Thirteen years had elapsed since Id last sailed SW offshore out of sight of land. Life had led me elsewhere, and years of neglect had been bestowed on the boat as it floated like a marine farm in Little Shoal Bay waiting patiently to, hopefully, be reactivated one day. Two young children, another boat, and a full-time job in another hemisphere had led to the long wait for reactivation.

However, that day finally came and turned into two years of methodical though sporadic work. SW all 17 feet 9 inches (5.4 metres) of her sat up the driveway at home on a cradle, well away from the water. She was high and drying out, and there was a lot to do. The term refit was well used in many conversations and I became skilled at explaining what I was generally taking too long to do.

The skeg which supported the long, narrow rudder had always tormented me, and for 20 years I had never been able to eradicate the movement and crack line that lived where the skeg met the hull. In 1987 I added another bolt and sheared off the heads of two others from over-keen tightening then filled and glassed the crack, but all to no avail. I had finally settled on defeat and the sight of water seeping from the crack whenever we took to the piles for a quick scrub-down.

To start with, a good drying-out was required all round. The old skeg was hack-sawed off, leaving three gaping bolt-holes in the bottom of the boat. It didnt look seaworthy nor feel right, but I knew it was inevitable: I had become committed to making a new one. All other unscrewables were unscrewed and many little holes left everywhere. Bigger, gaping orifices appeared when I took out the old crazed Lexan windows and the Perspex dodger.

One year had passed, and all I had done was to turn SW into the bare shell of the boat she used to be. It was a bad look. At this stage I was only a quick chainsaw-cut away from turning SW into an adventure playground for the children. A small-person-sized incision with a slide coming out of the side But somehow the resolve to sail again another day was found, and another year that felt and looked more productive went by as SW slowly improved in appearance.

Frank, the live-in temporary childminder (and family friend), was holding the fort while Karyn and I talked to each other in public doing the Kiwi FM radio breakfast show each weekday morning. Frank showed me how to laminate plywood, with grave attention to epoxy brews and clamping. He was working as often as possible on his own 12-metre William Atkin yacht Alana B at Span Farm down the road each day, and his expertise and determination to get his boat out of the mud and back to sea was inspirational.

A new skeg with carefully buried new bolts and gudgeons was laminated up, then bolted on with plenty of glue and sheathed in fibreglass, most wonderfully. It felt that the skeg/crack equation might finally be solved.

The other big one was the bottom of the keel. Over the years on the mooring, growing mussels and long tentacles of kelp, SW s keel had suffered. The fibreglass cloth that sheathed the steel and internal lead had peeled away and flapped like wings in the sea. The bottom of the steel keel that encased the lead had slightly opened up and the base plate had rusted away in places.

I made up a cardboard template of the shape of the lower part of the keel, and local steel fabricators Fagan and Hannay made me up a new keel-shoe with a 12-mm base plate and 3-mm rolled aerofoil sides, at no considerable expense to myself. Id foolishly thought there could have been some fiscal favouritism, given our shared surnames, but I was wrong.

Id also met Zein, through a friend Gawaine. Zein is mechanical and practical and can weld as well. After continuous pestering he agreed to do the job, and welded the new keel additions on to where they needed to be. He did a grand job underneath the hull, with sparks and his hot jet of burning danger making the welding process look like a glue gun in a kindergarten (apart from the necessity for a mask and his insistence not to stare at the flame). Zein assigned me the role of sitting inside the cabin with a fire extinguisher, waiting for the potential flames to spurt up from the over-heated keel and attached wooden hull. After a late night the night before, I fell asleep inside and fortunately was not consumed by fire.

The self-steering trim tab attached to the aft edge of the rudder had long since disappeared through electrolysis of its pintles and the relentless encouragement of wind and waves wobbling it about in Little Shoal Bay. A new one, made of hardwood sheathed in cloth and resin, and a little larger in blade surface area, was eventually fashioned and fitted with new pintles. The need for continuous, accurate steering when sailing solo can easily be overlooked. The trim tab is a vital piece of the self-steering wind-vane, and without it long-distance solo sailing in SW would be more difficult than worth doing.

In the engine room, the situation had deteriorated over the years and now appeared fairly dismal. Id done a lot of miles with the original old 7-hp Honda air-cooled petrol inboard. The engine plus its water-cooled exhaust pipe and associated water pump had got to know the impatient side of me.

Id had them both out of the boat before, entailing a minor but annoying odyssey of blind unbolting in a very inaccessible space. This time I gave it to Zein at Gawaines workshop to assess. He undid a few bits, and laughed in a way that I had not witnessed him do before. I knew immediately that prospects for engine rejuvenation were not looking good. Prior to taking SW out of the water for a while, the engine had seized and I found out that Id forgotten where the oil was supposed to go. I had mistaken the gearbox oil hole for the important one.