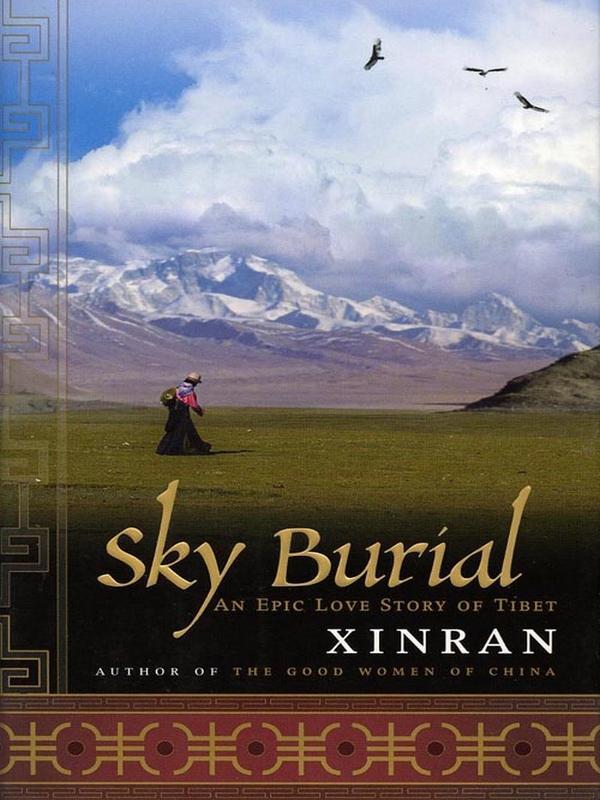

In the world of fiction reviewing, extraordinary is an over-used word. Yet there really is no other way to describe Chinese author Xinran's second book, Sky Burial. It is extraordinary in so many ways-the subject matter, the setting, the central character, but mostly its authenticity and the author's continuing search for the woman whose life is told here.

Sky Burial is the true story of a Chinese woman's 30-year search through Tibet for news of her lost, presumed dead, husband. Xinran is working as a radio journalist on a women's programme when a listener calls in to tell her about Shuwen. Xinran travels hundreds of miles across China to interview her and, over two days, Shuwen opens her heart and reveals her tragic, scarcely imaginable life story. Xinran returns to her life and spends the subsequent 10 years trying to find Shuwen again, researching her story and writing this book-a homage to an ordinary woman's extraordinary life-long search for the truth.

The story is a simple one: Shuwen meets her intelligent, idealistic husband-to-be while they are both training to be doctors. After less than 100 days of marriage, Kejun travels to Tibet as a Chinese army doctor and before long, Shuwen is notified that he has died in an "incident". Shuwen decides to join the army herself, travel to Tibet and find out if he really is dead, and if so, how and why he died.

And then, as if travelling to a closed country like Tibet as a young woman in the 1950s is not difficult enough, Shuwen quickly becomes separated from her unit and, close to death herself, is taken in by a family of Tibetan nomads. Her transformation from Chinese doctor to nomadic Buddhist is a long, painful and at many turns, deeply distressing one.

Sky Burial is a slight book-little more than an extended short story-and yet the ground it covers is immense, not just because of the fascinating glimpse it offers into a land and a people still largely unknown in the West. Despite its tragic themes of loss and survival in one of the world's harshest landscapes, it is an uplifting tale of unwavering loyalty and immeasurable inner strength. -Carey Green

PUBLISHERS NOTE

This version of Sky Burial differs slightly from the Chinese original. During the translation process, the author worked with her translators and editor to make sure that all elements of the book were accessible to non-Chinese readers.

In Chinese names, the surname is placed before the first name. Shu Wens first name is therefore Wen.

In 1994 I was working as a journalist in Nanjing. During the week, I presented a nightly radio program that discussed various aspects of Chinese womens lives. One of my listeners called me from Suzhou to say that he had met a strange woman in the street. They had both been buying rice soup from a street vendor and had started talking. The woman had just come back from Tibet. He thought that I might find it interesting to interview her. She was called Shu Wen. He gave me the name of the small hotel where she was staying.

My curiosity awakened, I made the four-hour bus journey from Nanjing to the busy town of Suzhou, which despite modern redevelopment still retains its beauty-its canals, its pretty courtyard houses with their moon gates and decorated eaves, its water gardens, and its ancient tradition of silk making. There, in a teahouse belonging to the small hotel next door, I found an old woman dressed in Tibetan clothing, smelling strongly of old leather, rancid milk, and animal dung. Her gray hair hung in two untidy plaits and her skin was lined and weather-beaten. Yet, although she seemed so Tibetan, she had the facial characteristics of a Chinese woman-a small, slightly snub nose, an apricot mouth. When she began to speak, her accent immediately confirmed to me that she was indeed Chinese. What, then, explained her Tibetan appearance?

For two days, I listened to her story. When I returned to Nanjing my head was reeling. I realized that I had just met one of the most exceptional women I would ever know.

I never saw her again, but her story did not leave my mind, so finally I felt I must share it with others.

1 SHU WEN

Her inscrutable eyes looked past me at the world outside the window-the crowded street, the noisy traffic, the regimented lines of modern tower blocks. What could she see there that held such interest? I tried to draw her attention back.

How long were you in Tibet?

More than thirty years, she said softly.

Thirty years! But why did you go there? For what?

For love, she answered simply, again looking far beyond me at the empty sky outside.

For love?

My husband was a doctor in the Peoples Liberation Army. His unit was sent to Tibet. Two months later, I received notification that he had been lost in action. We had been married for less than a hundred days.

I refused to accept that he was dead, she continued. No one at the military headquarters could tell me anything about how he had died. The only thing I could think of was to go to Tibet myself and find him.

I stared at her in disbelief. I could not imagine how a young woman at that time could have dreamed of traveling to a place as distant and as terrifying as Tibet. I myself had been on a short journalistic assignment to the eastern edge of Tibet in 1984. I had been overwhelmed by the altitude, the empty awe-inspiring landscape, and the harsh living conditions.

I was a young woman in love, she said. I did not think about what I might be facing. I just wanted to find my husband.

I had heard many love stories from callers to my radio program, but never one like this. My listeners were used to a society where it was traditional to suppress emotions and hide ones thoughts. I had not imagined that the young people of my mothers generation could love each other so passionately. People did not talk much about that time, still less about the bloody conflict between the Tibetans and the Chinese. I yearned to know this womans story, which came from a time when China was recovering from the previous decades devastating civil war between the Nationalists and Communists, and Mao was rebuilding the motherland.

How did you meet your husband?

In Nanjing, she replied, her eyes softening slightly. I was born there. Kejun and I met at medical school.

That morning, Shu Wen told me about her youth. She spoke like a woman who was unused to conversation, pausing often and gazing into the distance. But even after all this time, her words burned with love for her husband.

I was seventeen when the Communists took control of the whole country in 1949. I remember being swept up in the wave of optimism that was flooding China. My father worked as a clerk in a Western company. He hadnt been to school, but he had taught himself. He believed strongly that my sister and I should receive an education. We were very lucky. Most of the population at this time were illiterate peasants. I went to a missionary school and then to Jingling Girls College to study medicine. The school had been started by an American woman in 1915. At that time there were only five Chinese students. When I was there, there were more than one hundred. After two years, I was able to go to the university to study medicine. I chose to specialize in dermatology.