On a Spaceship with Beelzebub

BY A GRANDSON OF GURDJIEFF

david kherdian

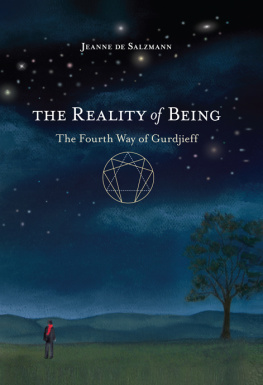

Inner Traditions

Rochester, Vermont

Dedicated to all those I studied with, and fought with, and with whom I prayed: for whether in agreement, disagreement, hostility or accord, they were the course of study to be passed through on the way to liberation and personal freedom.

And to G.I. Gurdjieff, who provided the means.

It was the very essence of Gurdjieff s teaching that the pupil must stand on his own feet and he took every measure, sometimes apparently harsh and brutal, to break down any tendency towards dependence upon himself. He would go to the length of depriving himself of much-needed helpers in his work rather than allow a relationship of dependence, or subordination. At the same time, he took for granted that a teacher is necessary and made it clear why this is so. No man can work alone until he knows himself, and no one can know himself until he can be separate from his own egoism. The teacher is always needed to apply the knife, to sever the true from the false, but he can never work for his pupil, nor understand for him, nor be for him. We must work, and understand, and be, for ourselves.

J.G. Bennett from TALKS ON BEELZEBUBS TALES, page 14

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

T his is the story of my discovery of the Gurdjieff workthe most powerful, effective and meaningful system of esoteric teaching ever to come to the West. It is also the story of my search for someone who could pass on to me Gurdjieffs powerful method of self-development, who could teach it in the way that he had intended it to be taught.

Freedom. To be free. Inside myself. Freedomand all that it means to meis what ultimately brought me to the door of the Gurdjieff work. When I began my search, it was an idea that seemed to imply a possibility that nothing in life could answer. And although I was trapped in life, there was a part of me that yearned for something that would set me free. Now, having searched for, and found, an answer of my own to the question of inner freedom, my meaning of freedom is simply this: to know why I am here, and what I was intended for.

I have pondered for a long time the mission of Gurdjieffs Fourth Way teaching because I need to understand the obligation I have assumed by practicing his ideas. I had begun to do this work from my own egoistic needs, but Gurdjieff had said, You must first be out and out egoist before you can become altruist. Although I can see the egoistic side, my experiences in the work have not answered the question of what the altruistic side means, especially since the Gurdjieff work, as it is today, has no intention of taking its place in the world.

But before I can properly tell my story, I ought to address one obvious question: Who exactly was Gurdjieff? He was, and remains today, a mysterious figure. Perhaps this is so because he was on a higher level than we are, and we are unable to judgeor even seeanyone who is on a higher level than ourselves. And Gurdjieff was many steps removed from the platform on which the rest of his disciples stood.

He was born in the Caucasus, and raised in the city of Kars, a melting pot of Christian and non-Christian races. Gurdjieffs question, the idee fixe of his inner world, that arose in his mind in early youth, was this: What is the sense and significance of life on the earth in general and of human life in particular? While still a young man his travels took him to Persia, Turkestan, Tibet, India, the Gobi desert and Egypt, in an unremitting search for a real and universal knowledge. His travels in search of hidden knowledge carried him deeper and deeper into Asia, and eventually led him to a source of wisdom in which others before him had also been initiated.

Gurdjieff was unusual not only because he was able to weld a diversity of esoteric disciplines into a single method, but because the method that he conceived was tailored for the West. To participate in an Eastern teaching, with which the West has been fairly inundated, the student must change their garment of culture and memorize a lexicon of foreign words and prayers. But in Gurdjieffs method, the essential work of translation had already been doneby Gurdjieff. He was able to make his ideas palatable to the psychologically and scientifically oriented Westerner who was suspicious of anything that hinted of religion or dogma. The religious and spiritual sources of his method were therefore well hidden, and the true meaning and purpose of his Workas he called ithad to be discovered privately and individually by the seeker. If the student could not find his way for himself, he soon became another rat for my experiments, as Gurdjieff liked to boast, for he had his own mission, of which he never spoke.

Gurdjieff did not become a visible presence until around 1912, when he appeared in St. Petersburg, surrounded by students. It was soon after that P.D. Ouspensky met Gurdjieff, having searched on his own for esoteric knowledge. Ouspensky was a Russian journalist who meticulously recorded the teaching as Gurdjieff gave it during the early years in Russia, and on the long flight from Russia to the West.

The First World War obliterated Gurdjieffs plans to found an institute in Russia. His flight from Russia to the West is recorded in Thomas de Hartmanns Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff , the most heartfelt of all the books about Gurdjieff.

Together with his band of pilgrims, Gurdjieff founded his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at the Chateau du Prieure, near Fontainebleau, in 1922. He would devote the rest of his life to bringing to the West what he had discovered in the East. To do this he created an exact language and, with de Hartmann as his amanuensis, produced the haunting melodies needed for his movements, the sacred dances he had observed in the temples of the East, and that he had reformulated for the purposes of his teaching.

These movements, more than any other method, conveyed by direct experience what Gurdjieff meant by balancing the centers. He contended that we were not normal because our emotional, mental and physical centers were not in accord, for the reason that they had not been properly educated and trained. The movements, although they could not be called sacred dances as practiced by his pupils, did impart a feeling of spirituality that words by themselves could not convey. These were not only an embodiment of the Work in action, but proof of its result.

His Russian pupils were joined by members of the English nobility, as well as English and American writers, artists, and intellectuals. These were his earliest students. Gurdjieff was concerned to make his ideas and his presence known to the West. He had come on a mission, as a Herald of the Coming Good, the title of the one book he issued in his lifetime. Among his early pupils, in addition to Ouspensky, who was already a famous writer in Russia, and Thomas de Hartmann, the composer, also famous in Russia, were Alexandre de Salzmann, an artist and stage designer; his wife Jeanne, a dancer; and A.R. Orage, the editor of The New Age, whom George Bernard Shaw had called the worlds best living editor. Orage not only assisted in the translation of Gurdjieffs monumental work, All and Everything: Beelzebub s Tales to His Grandson, but it is questionable whether that work would have achieved its final, completed form without his assistance. There were also Jane Heap and Margaret Anderson, artist and writer, who together edited The Little Review, the most influential literary magazine of its time. Other writers of significance who would spread the ideas were Kathryn Hulme, Fritz Peters, and Jean Toomer.

Next page