CHAPTER XV

At first, Pauls words had no effect on me. I heard what he said but the information made no impact. I may have been slightly shockedI remember a feeling of joy and satisfaction that Iskra was at last sailing as she ought to sail. She seemed to be flying after the hours of slog, swerving and side-stepping with all her old agility and grace, flirting with the waves, sometimes taking a white crest and flinging it defiantly across the deck, feinting, dodging, parrying. She was carrying the right amount of sail. It was blowing hard but not more than she could managethe seas were big but nothing to worry her now that she was free. I knew that it was only because she had been tied up and helpless that she had been overwhelmed. There was a fair lot of water in her. I saw it slopping over the cabin sole and instinctively my hand went to the pump. Then I saw the strop for the tackle on the starboard sidethe hook was still fast to it. The tackle had run free leaving the bare end trailing in the sea. Now, looking back, I wonder whether it was only carelessness that had left the knot unmadethere may have been a significance in it. Perhaps some force inside me had ordained it. I remember it had come into my head two or three times during those days of preparation that I must put a stop-knot in the end of the tackle to prevent the rope from running out through the blocks. Somehow it was never done. I heard Paul say, impatiently, Well, come on man, what are you going to do about it? I came to my senses.

The night was blackthere was nothing to be seen outside the narrow radius of our visionno stars, no horizon not even the light on Turks. There was no sign whatever of the Integrity. She would be careering downwind with no restraint and with half a gale behind her. It was no more than a guess whether she would be driven ashore on the reef or whether she would sink firsteither way Bill was in dire peril. He had the float but in these conditions there was no telling how he would survive on it. Amidst the fury of the reef his chances were nil. Either way, the reef or the bottom, we had an hour to find him.

After she had recovered herself and had shaken herself free of the great weight of water, Iskra had fallen off on the port tack. Now she was sailing across the Turks Islands Passage at six knots, I guessed, on an easterly course with the wind fine before the beam. I looked in at the clock and noted the time. Noted the compass course. Well put her about, I said to Paul, Lee ho! She came flying into the wind and payed off easily on the other tack.

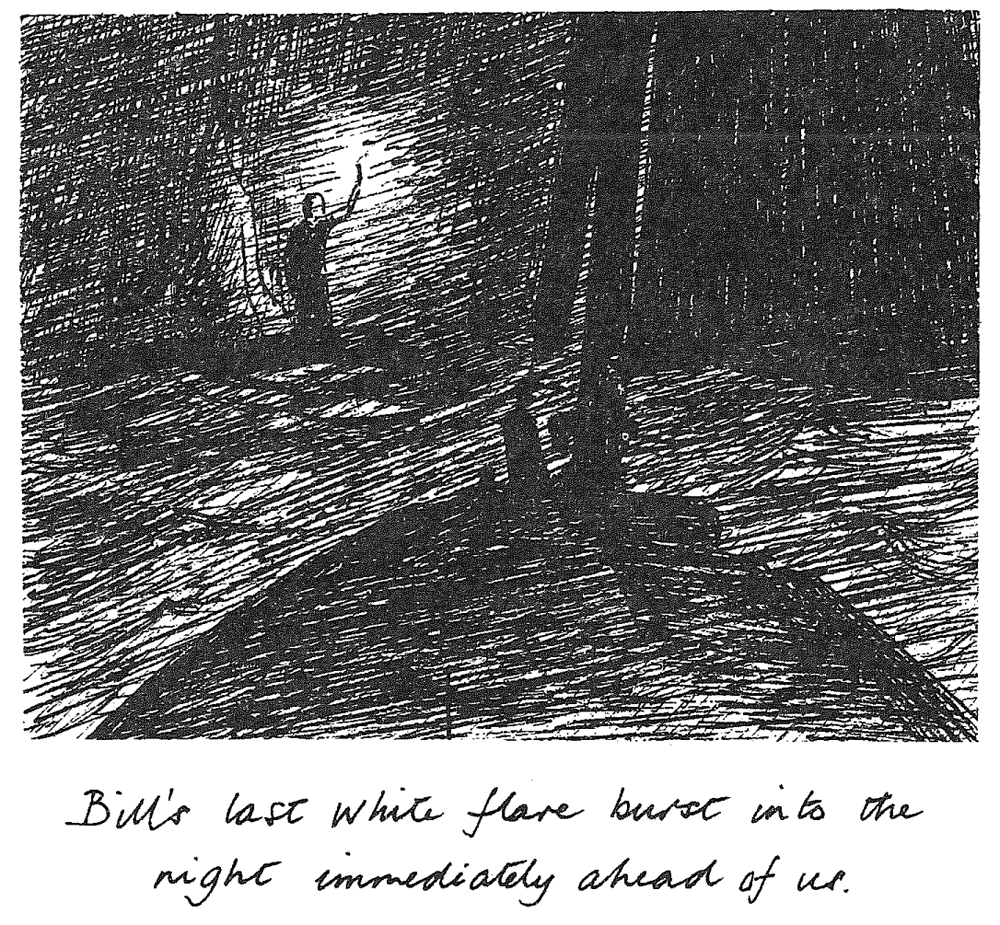

I did not know whether the same course had been maintained accurately since we lost the Integrity did not know the exact number of minutes that had elapsed, did not know the rate of the Integritys drift, could only guess at our own speed and leeway. On the reciprocal course Iskra had the wind slightly abaft the beam and she was going faster. I guessed we couldnt have been sailing away from the Integrity for more than ten minutes but we would have covered a mile in that time. We sailed back for a quarter of an hour and there was no sign of hernothing more than the black sea and the impersonal breaking waves with their momentary flashes of luminous white. I had allowed ten degrees for our own leeway and the Integritys drift. Perhaps it was too muchor not enough? Paul and I gazed into the night and the night threw our stare back in our faces. We put about again and surged across the other way, now luffing a fraction in case I had allowed too much. Five minutes this time and then about again and more down wind. Christ, we must have got too far down windhaul the sheets and make three short tacks close hauled. In half an hour we criss-crossed the ocean with a pattern of lines which lost all reason and all logic. We were ourselves lostlurching back and forth across the Turks Islands Passage blindly, hopelessly, searching through the blackness, peering into the opaque walls which oppressed us and served to deaden our sensesthe lost searching for the lost. Paul listened on the radio, holding it in his hand and talking at it as if he could conjure Bill out of the night with its magic. But I knew, we both knew, that its range was measured in yards. It had started to rain heavily and the wind had easedthe norther going through I guessedit would be fine in a couple of hours, or less. Now I could hear the reefoh Jesusthat uncompromising, low rumble, still faint but gaining in strength. We must be too far to the westLee ho! Nowit was a mindless, aimless, and thoughtless zig-zagan erratic darting from side to side without hope and without system. We lit our white flares until we only had one left. They blinded us so that we could see nothing through their brightness. I put about again with a sick, hopeless feeling of disaster and tragedy inside me. How could this ever be justified to myself, to anyone? There was no way in which blame could be denied or excused. A mere detail had brought disasteras happens at sea. I had learnt the lesson a hundred times and still I was ignorant of it. In seamanship every fragment of preparation is as important as every otherthe big and the small are all as equalsevery part interlocks with every other. A simple figure of eight knot in the bitter end of a tackle was left undonethe tackle ran through the blocks, the tow, with Bill on board, was lost. There wasnt much time left. I glanced in at the clockwe had been searching for the Integrity for forty minutesby now she would be near to sinking. Bill would be getting ready to leave her in the float, preparing himself for a journey which might be his last. I felt sick with apprehensionat best he would drift through the night to be picked up tomorrow or to be cast ashore on some deserted beach in North Caicos. At worst there was the reef. All this travail, all this expenditure of thought and effort and resources, culminating in failure and possibly in tragedy, for the sake of a worthless basket of rotten wood and sick nails. The guilt of it would hang round me for ever.

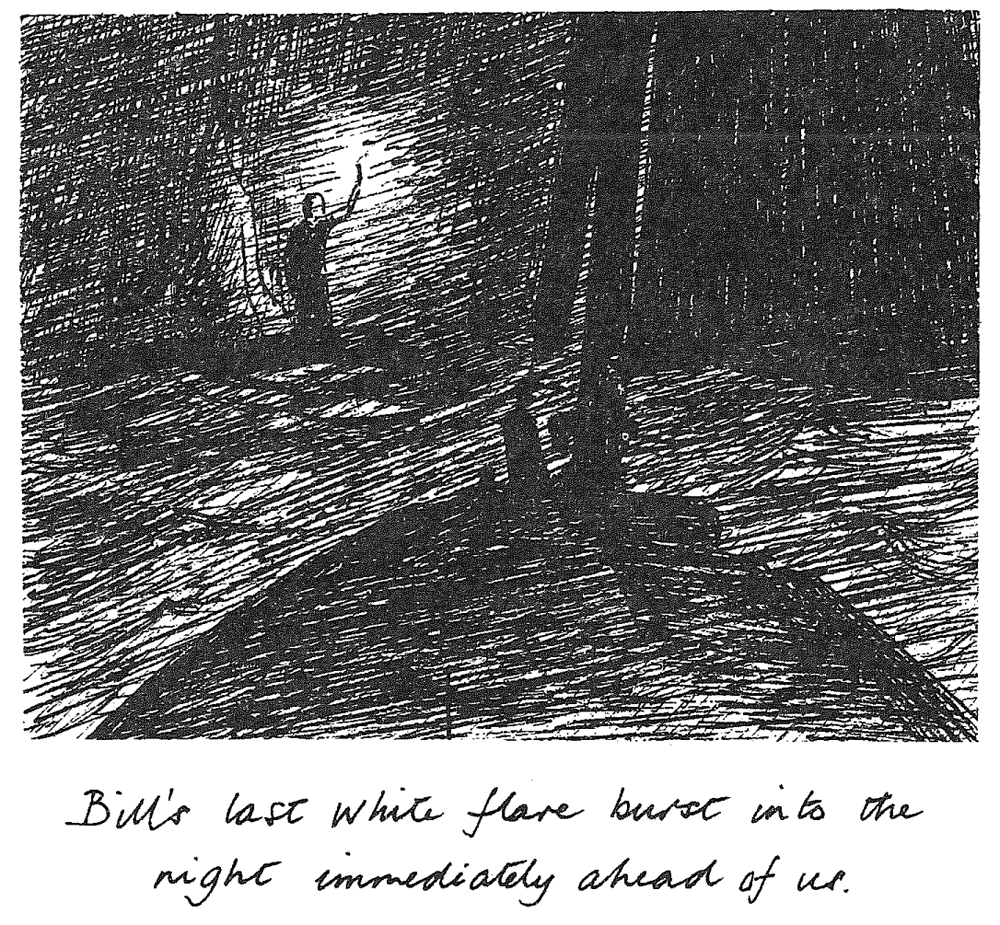

I didnt know what shortcoming it was in usarrogance perhaps or over-confidence or too glib an assumption of the seas good willthat had singled us out for this treatment. Suffice it that we were spared the ultimate priceforgiven the last penalty. The ocean is mysterious in its dispositions. Bills last white flare burst into the night immediately ahead of us, flooding the integrity and Iskra and a tight ring of the sea with a harsh, metallic brilliance as if we had been momentarily caught in the beam of a searchlight. The schooner was no more than a couple of boats lengths from the bowsprit endI put the helm hard down before Iskra ran full tilt into her. We looked at Bill and he at us in astonishment as we sheered alongside within feet of him. I thought you guys had gone home, he shouted, I guess youd better be quick. We could see every detail of the Integritys deck as Bill held the flare high above his head. The pump was still running and the water still tumbled out through the scuppers but now, instead of riding high and rolling in the seas, she was still in the water, low like a fully loaded barge and the waves were washing over her decks as if she was fastened to the bottom. She had the look of doom about herthere was no saving her now. I felt a profound relief which flooded through my bodya great happiness and a lightening of the spirit. The Integrity had never done harm to any person and in this she had remained true. She had met with adversity, she had suffered and she bore the scars of her misfortunes but she had never hurt any manhad never struck against those who had been associated with her. I glanced at Paul as Iskra came into the windthe tears were rolling down his cheeks.