It is the bliss of ignorance that tempts the fool, but it is he who sees the wonders of the earth.

It is in the nature of all of us, or is it just my own peculiar makeup which brings, when the wind blows, that queer feeling, mingled longing and dread? A thousand invisible fingers seem to be pulling me, trying to draw me away from the four walls where I have every comfort, into the open where I shall have to use my wits and my strength to fool the sea in its treacherous moods, to take advantage of fair winds and to fight when I am fairly caught for a man is a fool to think he can conquer nature.

Frederic Frite Fenger cruised his 17ft sailing canoe in the Caribbean, Grenada and the Virgin Islands singlehanded in 1917. The boat is in a museum at Bruce Mines, Ontario, Canada.

Dedication

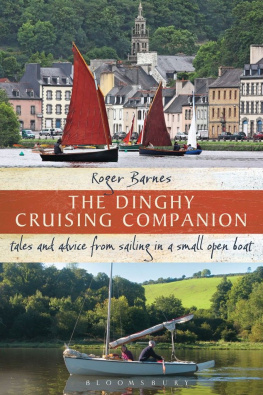

For Wanderer and the National Maritime Museum, Falmouth.

Wanderer in her final home, the National Maritime Museum, Falmouth (Chris Sayers).

The sailing exploits of Frank Dye and his wife Margaret are already known to thousands in many parts of the world. Yet to understand fully these cruises, why they are made and how they bring joy and satisfaction to these very skilled dinghy sailors, you really need to meet and know them. This book goes some of the way towards giving this insight into the compelling motivation that overcomes the hardship, discomfort and even fear which is the virtually inevitable accompaniment of such major cruises in notoriously difficult waters.

My feeling is that this book only goes some of the way towards giving the insight I mention. It is unavoidable that this is so if the accounts are to be written by the Dyes themselves as they most certainly should be. They are by nature incredibly modest, emphasising mistakes rather than achievements, embroidering nothing, starkly matter of fact. This should be ever-present at the back of your mind as you read this book.

Above all, please do not think that Frank Dye is a reckless fanatic who chooses to sail in perilous places just to see if he can and to prove his ability to survive some fairly advanced form of self-inflicted torture. He prepares his cruises with meticulous care and, perhaps having chosen a potentially dangerous area in which to sail for reasons which will be explained later, he does his utmost to reduce the dangers by good sound seamanship, which includes the foresight and caution that goes with experience.

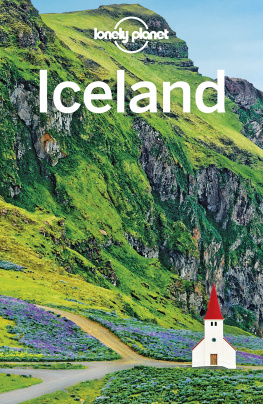

Why does he choose to go to these geographically inhospitable places? It is because small boats have always been a part of such places since before the Vikings. It is also because, if you arrived by ship or aeroplane as a visitor in such places, you would remain as a stranger watched from behind closed doors, but if you land from a 16ft (4.88m) dinghy, you are immediately taken into the houses and hearts of the people and get to know them as you could probably never do otherwise. This is perhaps the only way in which someone from the well-insulated modern world can get a glimpse at and the feel of that remarkable period of seafaring in which the Viking made such an impression.

It is a little sad that these following pages tell only of Wanderers ocean crossings, for she has been the Dyes partner in so much other sailing that may not be quite as impressive, but is full of interest, originality and achievement quite often flavoured with peace and quietude instead of rugged struggles with wind and sea. To me, that is all Wanderer and Frank and Margaret, and no part is more absorbing than the rest. Let us hope they will write about it all sometime.

A few years ago Wanderer sailed up to the bottom of my garden on the Hamble River, off the Solent. I had no idea they were coming, although I did know that they were sailing westwards along the English south coast from East Anglia. I happened to be in the garden that evening and I dont know why, but although there were then about 4,000 Wayfarer dinghies like Wanderer in existence and although the Hamble is full of sailing boats on the move almost all the time, I instantly recognised her when she was still about a quarter mile away, creeping over the shallows against the swiftly ebbing stream.

Weve come to take you for a sail, they said. Not just now, you wont, I replied, as the water uncovered the mud flats and left Wanderer high and dry. Next sailing 4am tomorrow morning. So we fed and talked and laughed that evening and were up before the sun as the water flooded over the marsh to lift Wanderer up again. I shall never forget the peace of that early morning on the Solent as we sailed along, brewing tea as Wanderer skipped happily over the scarcely ruffled water. This was another side to the character of the Dyes cruises that is less known and slips by unnoticed, yet is more within the ability of many to emulate and enjoy themselves.

Designing boats is my happiest occupation. And as each is designed, I seem to conjure up a vision of the chaps working to build the boat, the kind of people who will sail her, the conditions and the places in which she will sail and how she will cope with them for these are the people and the situations which will make the design come to life. I must confess that as I drew out the Wayfarer design I never visualised her riding out a gale on the way to Iceland, nor did I ever think that two such remarkable people as Frank and Margaret Dye would sail in her. They certainly have breathed an abundance of life into the Wayfarer design and in return Wanderer has become a part of their lives.

Ian Proctor

February 1977

Forty years ago I began sailing Wanderer, our Wayfarer sailing dinghy, on coastal and river cruises. In fact we were out every weekend learning, summer and winter, irrespective of weather fair and foul, and as our experience increased this developed into offshore passages. It was a slow gaining of knowledge which continues today.

Some four decades later I wonder what has changed? What has altered? What did I learn and when? With the benefit of hindsight what would I have changed? What mistakes? What pleasures? And was it worth it? What would I now do differently?

Since I was a small boy I have read endlessly about small boat voyages, about tough men, seamen and fishermen. No-one in the family sailed. We lived 40 miles from the sea, and my only experience of boats as a child was when my elderly grandfather took me out in his river punt when he wasnt babbing for eels of an evenin; paddling a childs canoe in the waves on the beach at Bacton; watching the fishermen launching off the beach; and, pleasure of pleasures being asked if Id like to go out with them for the day line fishing. I stood on the shore and dreamed of what lay beyond the next headland, and what lay invisible over the horizon.

Building up the family business which had run down during the war allowed me no time to follow my interest. Thus I was 27 years old before I again set foot in a boat and it almost ended in disaster. On impulse I bought an aluminium alloy 12ft (3.65m) sailing dinghy, lugsail rigged, with cotton sails and galvanised steel centreboard for 40. This sum was not a lot of money even in those days, and to me she looked a good boat and useful. My father offered to crew, and Sunday saw us lauching onto Wroxham Broad with little idea of what we were doing. Get that damnd tin boat off my starting-line. NOW! roared the Tannoy from the prestigious Yacht Club amongst the sound of booming cannon, for all to hear.

Next page