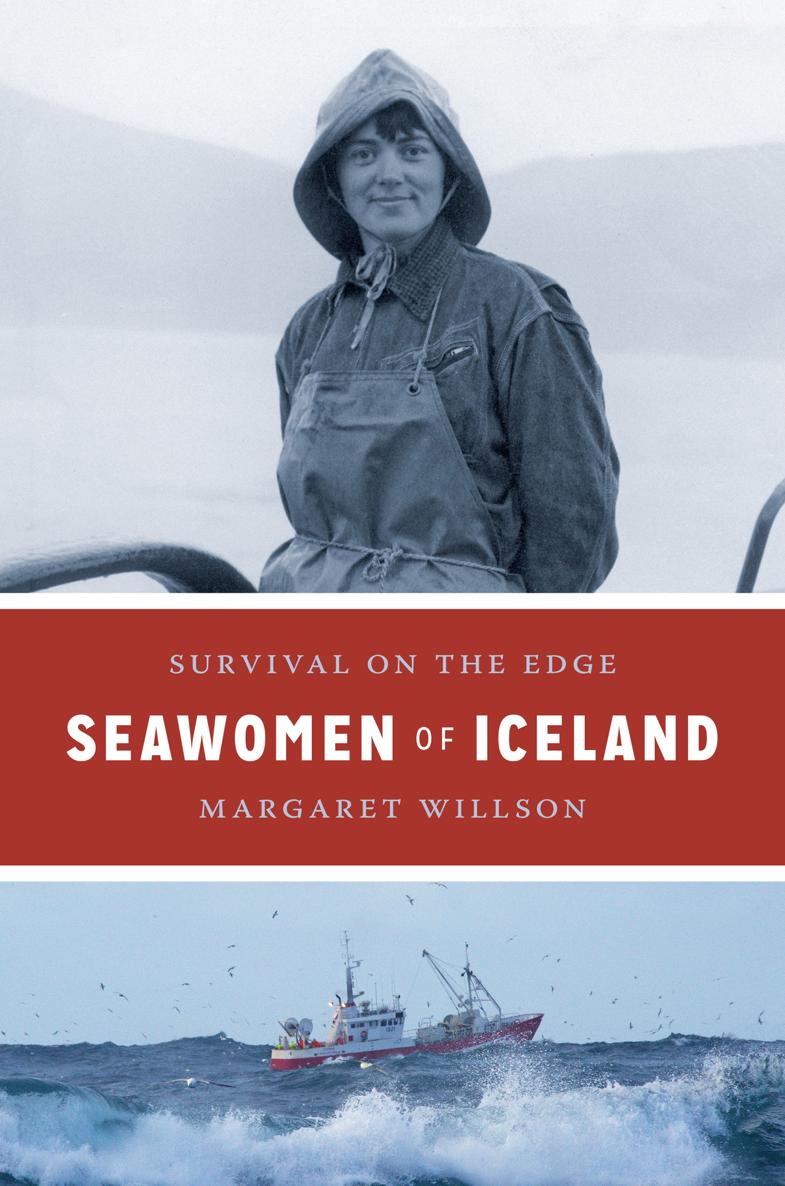

SEAWOMEN OF ICELAND

MARGARET WILLSON

SEAWOMEN OF ICELAND

SURVIVAL ON THE EDGE

Seawomen of Iceland is published with the assistance of a grant from the Naomi B. Pascal Editors Endowment, supported through the generosity of Nancy Alvord, Dorothy and David Anthony, Janet and John Creighton, Patti Knowles, Katherine and Douglas Raff, Mary McLellan Williams, and other donors.

EPIGRAPH: H. Jnsson 1949, 39.

2016 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Design by Thomas Eykemans

Composed in Warnock, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

Display type set in Mission Gothic, designed by James T. Edmondson

20 19 18 17 16 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Willson, Margaret, 1953 author.

Title: Seawomen of Iceland : survival on the edge / Margaret Willson.

Description: Seattle : University of Washington Press, [2016] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015046198 | ISBN 9780295995502 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Women fishersIceland. | Women fish trade workersIceland. |

Women in fisheriesIceland. | WomenIcelandSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC HD6073.F672 I739 2016 | DDC 331.4/8392094912dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015046198

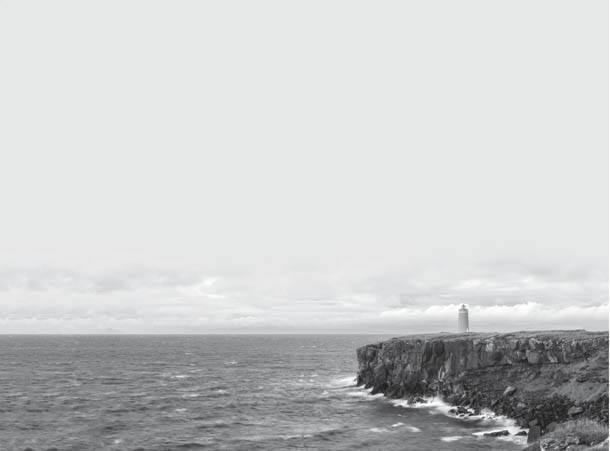

FRONTISPIECE: Holmbergs lighthouse, region of Vestfirir, Iceland. Courtesy Diego Delso.

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

To the seawomen of Iceland,

both of today and in the past

I beg of the blood-haired waves,

Whose frothing veils harass,

Haughty sea-goddess daughters,

Please will you spare my ass.

Bi g hddur blugar

bregi upp faldi snum

Rnardtur reisugar

rassi a vgja mnum.

Bjrg Einarsdttir, seawoman and poet

North Iceland, mid-1700s

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AS WITH SO MANY BOOKS, THIS ONE WAS POSSIBLE ONLY THROUGH the support and collaboration of many people and groups.

I am deeply grateful for funding provided by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research and the National Geographic Society for fieldwork and research, and to the American Association of University Women for a writing grant.

People in Iceland, in general, were so open, generous, and kind to me during the research and writing of this book, I will have trouble thanking them all. Firstly, there are the seawomen themselves, too many to be named, who welcomed me into their homes, and who trusted me with their memories, adventures, and insight. It is to them that I dedicate this book. My dear friend gsta Lyons Flosadttir helped me to understand so much about Iceland: its history, politics, and the complex fabric of its society; I also owe her a great deal. Her extended family in Iceland welcomed me as though I were an American relative, a hospitality of spirit that transformed my time there.

Several research assistants and associates accompanied me during various phases of this research, literally making connections with seawomen possible. Anna Andersen and lfrn Sigurgeirsdttir were valued early research assistants, and I thank them for their help. Birna Gunnlaugsdttir became my major field assistant, accompanying me through numerous adventures and exploits, helping me to understand histories and complexities between communities and people in Iceland. ra Lilja Sigurardttir worked as my historical, archival, and library research assistant; this research was possible only because of her engagement as well as her research and organizational skills. Helga Tryggvadttir very generously not only shared the statistically based material she had previously compiled on Icelandic seawomen but then worked with me to collect and compile the more extensive data that inform this volume. I would also like to thank the various staff of the Icelandic Maritime Administration for their time and for making available to us data that made such statistical analysis possible. Vilbergur Magni skarsson, director of the School of Navigation, also generously shared time and knowledge with me. I also very much appreciated Jsef Hlmjrn sharing with me his extensive knowledge of Icelandic fishing history and outstation life. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists in local libraries, museums, and archives of the various communities Birna and I visited throughout Iceland, who gave considerable time and effort searching for local material unavailable anywhere else. The same goes for so many people, in various communities and too many to name, who shared their considerable local historical knowledge with me. Sigurlaug Gunnlaugsdttir and Gylfi Pll Hersir of Reykjavk generously shared their home with me, and became cherished friends in the process. Margrt Brynjlfsdttir kindly opened her home and gave her support to me, a researcher she hardly knew, while I was in Patreksfjrdur. Hrafn Heimisson in Hfn also generously offered his hospitality for the time Birna and I spent there talking with seawomen.

Various members of the University of Iceland were remarkably supportive, sharing their knowledge, insights, and connections with me. As I began this research, Gsli Plssons immediate open support and encouragement meant a great deal, and I thank him. Also, Terry Gunnell was always very generous with his knowledge and time. Thorgerdur Einarsdttir gave appreciated help in directing me to writings on Icelandic gender and women as I began this research. Katrn Anna Lund and Anna Karlsdttir shared with me their considerable knowledge, becoming collaborators and friends. Unnur Ds Skaptadttir and Kristn Loftsdttir also became cherished friends, sharing with me articles and other material that informed this book. Even various staff at the University of Iceland cafs, where I spent considerable time and drank numerous cups of coffee, showed me kindness in encouraging me to speak Icelandic with them, even though they all spoke English fluently. Nels Einarsson of Akureyri also shared with me his considerable knowledgeand laughterhelping me to understand the complexities of Icelandic and international fisheries policies. Ragnhildur Bragadttir very kindly shared with me her unpublished work on the Icelandic seawomen. The staff of the Maritime Museum in Reykjavk has likewise been incredibly supportive from the first time I visited, explaining to me various specifics of boat and fisheries history. From the Museum, I particularly wish to thank ris Gyda Gudbjargardttir and Alma Sigrn Sigurgeirsdttir for sharing with me material they had already collected on seawomen. ris Gyda Gudbjargardttir also found some of the historical photographs I have included in the book. To all of these people, I am deeply grateful.