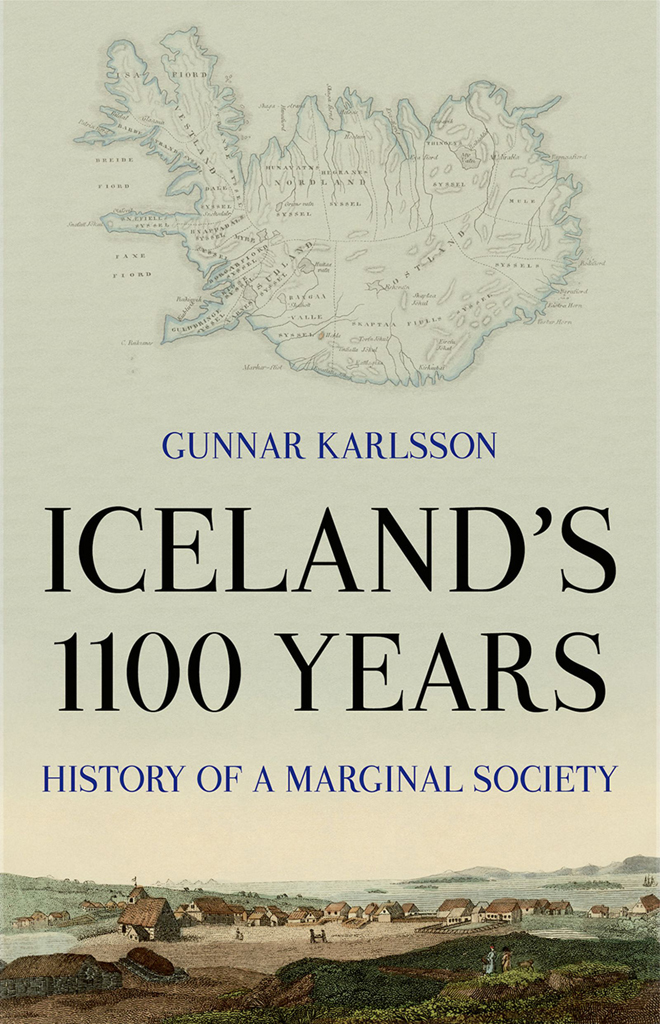

ICELANDS 1100 YEARS

GUNNAR KARLSSON

Icelands 1100 Years

The History of a Marginal Society

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.

41 Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3PL

Gunnar Karlsson, 2000

This paperback edition, 2020

All rights reserved.

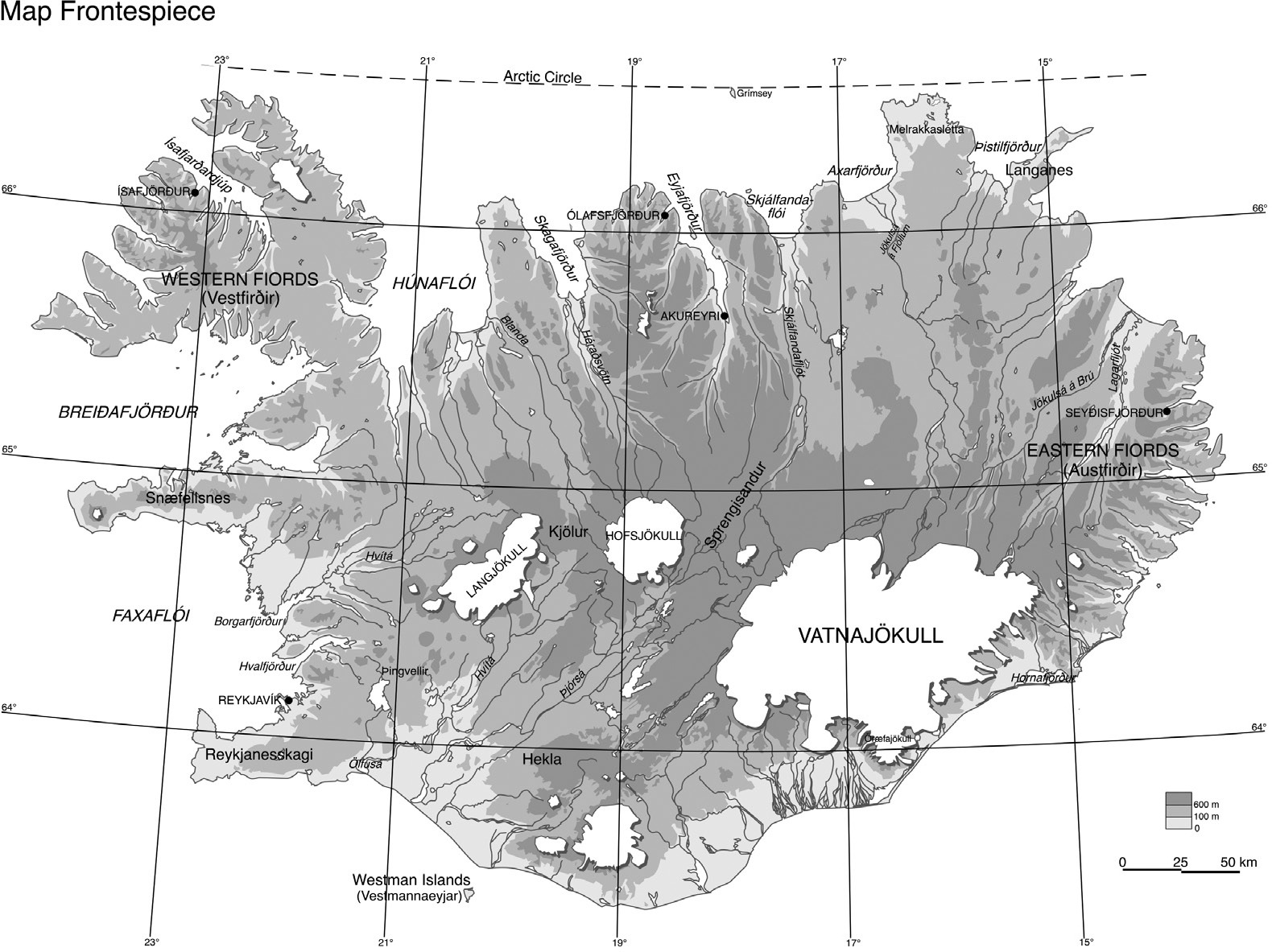

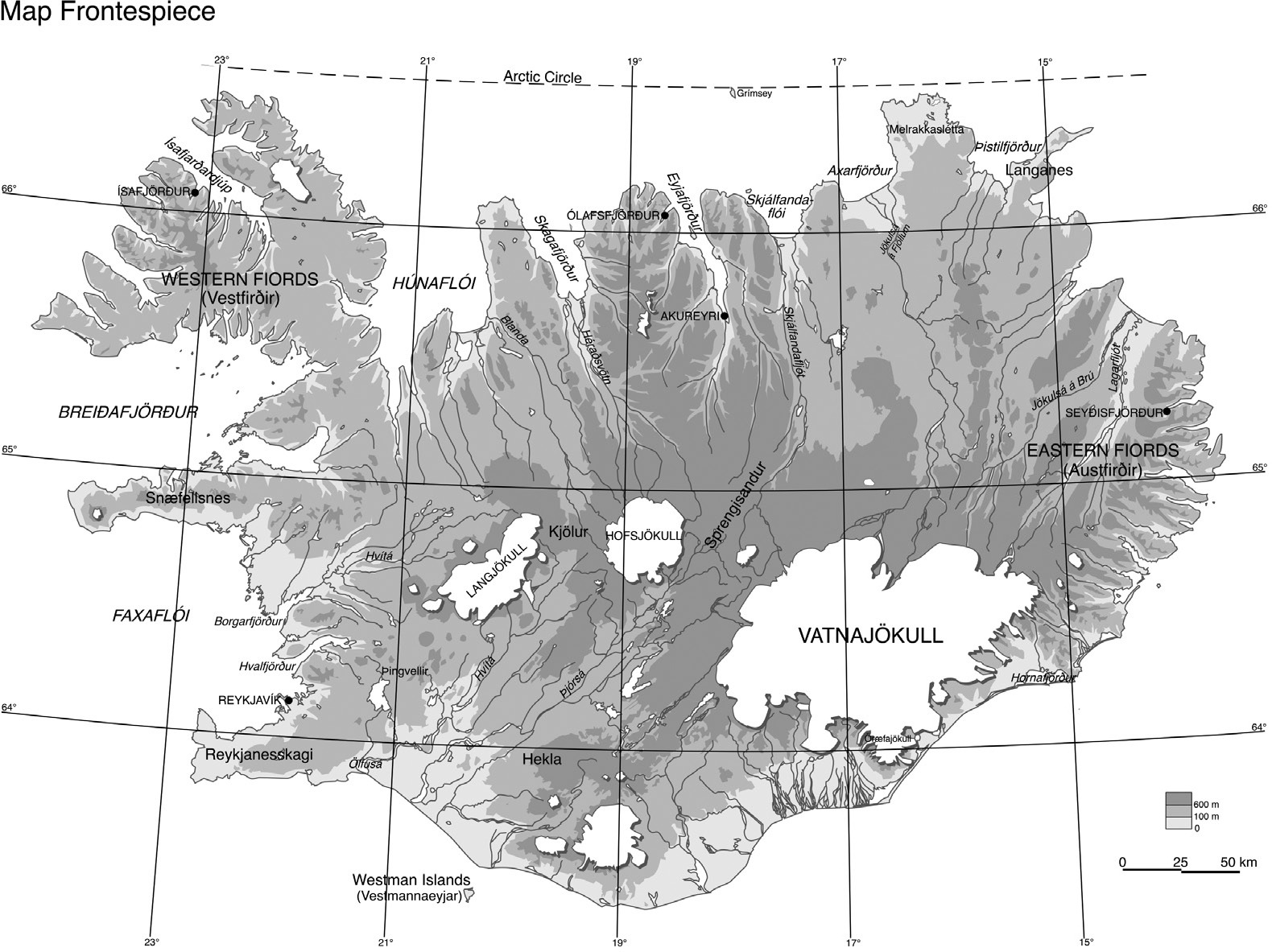

Maps and diagrams by Jean-Pierre Biard

Printed in the United Kingdom

This book is printed using paper from registered sustainable and managed sources.

ISBN 9781849049115

ISBN 9781787384538 (e-book)

www.hurstpublishers.com

CONTENTS

Illustrations

Maps

Figures

Tables

The present book is a republication of the original edition of 2000. Apart from the correction of my error in placing Iceland not far from the western coast of Greenland (p. 9), nothing substantial has been altered from the previous edition, until the 1990s. New works have been added only where appropriate, mainly in footnotes. The narration of 21st century events begins with the President of the Republic moving to change the role and power of his office through use of the veto ( (Post-war Politics) covers the political history of the unprecedented financial expansion of the 1990s and early 2000s, followed by the sudden collape of all the major banks in the autumn of 2008. Another notable addition to this text is the tourist boom of recent years, which has brought about significant changes to the composition of the Icelandic economy.

I am sincerely thankful to those who have helped me to refine the text, either by giving their good advice or by making improvements to my imperfect English. That said, I take full responsibility for all that is said in this book.

Reykjavk, 16 May 2019

GUNNAR KARLSSON

Writing a substantial one-volume history of my home country for publication in English has been only my agenda ever since I taught Nordic history at the Department of Scandinavian Studies, University College London, in 19746. However, other tasks appeared more urgent, until in 1995 when Christopher Hurst, directed by our common friend Sigurur A. Magnsson, approached me about the subject and even managed to convince me that I would be able to write the text in English. This was more than dubious, but anyway that was how the work started and proceeded, with a great amount of help from many people, to whom I am sincerely thankful.

My wife Silja Aalsteinsdttir read my first draft chapter by chapter as I wrote it, corrected my worst linguistic errors and encouraged me to go on with the work. A fellow historian and dear friend Helgi Skli Kjartansson read the whole manuscript and helped me immensely in erasing factual errors and in finding appropriate terms in English for concepts of Icelandic history. Five of my colleagues at the Institute of History, University of IcelandHelgi orlksson, Loftur Guttormsson, Anna Agnarsdttir, Gumundur Hlfdanarson and Gumundur Jnssonwere allocated the part of the manuscript that came closest to his or her field of study, and each of them read it carefully and suggested important improvements. Two more Icelandic historians were great help to me: Orri Vsteinsson and Valur Ingimundarson borrowed my text at the manuscript stage and use it in a course in Icelandic history in English at the Univeristy of Iceland, and both returned it with a number of valuable remarks. Christopher Hurst and Munizha Ahmad have done their best to transform my text into proper English. Anna Yates also read a proof of the text and made valuable corrections and suggestions for improvements.

Furthermore, I have had a pleasant collaboration with Jean-Pierre Biard, who drew most the maps and diagrams. Hrur gstsson allowed me to use his drawing of the suggested timber construction of a medieval framhouse (fig. 1.71). Rbert Guillemette lent me his diagram of a pattern of a saga feud (fig. 1.91). Illustrations have also been provided by the National Museum of Iceland, the National Library and the photographer Mats Wibe Lund. A fund for promoting progress of education at the University of Iceland (Kennslumlasjur) has helped me to cover expenses, for instance for Jean-Pierre Biards work. Translations of Jnas Hallgrmssons poems are printed in Chs. 1.19 and 3.2 by kind permission of the translator, Richard N. Ringler.

The manuscript was mostly written in 19968. Since then I have tried to incorporate new subect matter up to this year, in regard both to historical occurrences and historical research. However, in many cases statistical information in the book goes only to the early 1990s, and it is more than likely that some of the newest research results have escaped my attention. And from today the editing process is closed; not even the founding of a new political party, which will almost certainly take place in early May (see Ch. 4.8), will be related in this edition of the book.

Reykjavk, 11 April 2000

Gunnar Karlsson

Most Icelanders use patronymics and not family names. It follows from this that it sounds natural to mention a person, even a complete stranger, by his or her first name alone. Thus it is not a sign of over-familiarity when the author speaks of Jn Sigursson, Icelands national leader in the 19th century, as Jn. Thus Icelanders are placed in the order of their first names in the Bibliography and Index.

The names of Viking Age and medieval Icelandic people are written in the same way as in publications of medieval Icelandic texts with a normalized orthography. Thus the name of the discoverer of America is written Leifr Eirksson, or in an anglicized form: Leif Erikson. The same applies to Scandinavians until the 14th century, when their names take on modern forms, which are English rather than Scandinavian. Most Icelandic place names, on the other hand, are still today attached to the same places as in early times and are therefore written from the beginning in the modern Icelandic form: Flugumri, not Flugumrr; Haukadalur, not Haukadalr; Sklholt, not Sklaholt.

Old Norse as well as modern Icelandic is written with some letters that are unfamiliar to most English readers. The letters , , and denoted long vowels in the medieval language, but now stand for diphthongs (see Ch. 17). The difference between i and , u and , was also one of length in the old language, but now they have different values: i is like i in pin, like ee in see; is similar to English u in loom and womb, while u has no close equivalents in English. In modern Icelandic y and have the same values as i and . sounds similar to u in but. / and / denote a fricative: is the voiced variant, like th in brother and weather, and the unvoiced one, like th in thin.

The alphabetical order which is followed in the bibliography and index of the book is:

a/, b, c, d, , e/, f, g, h, i/, j, k, l, m, n, o/, p, q, r, s, t, u/, v, w, x, y/, z, , ,

Iceland

In the national anthem of Iceland, written when the millennium of settlement in the country was celebrated in 1874, the poet and clergyman Matthas Jochumsson alluded to King Davids words in Psalm 90: For a thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday when it is past, and as a watch in the night. Pastor Matthas wrote: