EXCESS

'The country's international reputation is ruined.'

Financial Times, October 19, 2008

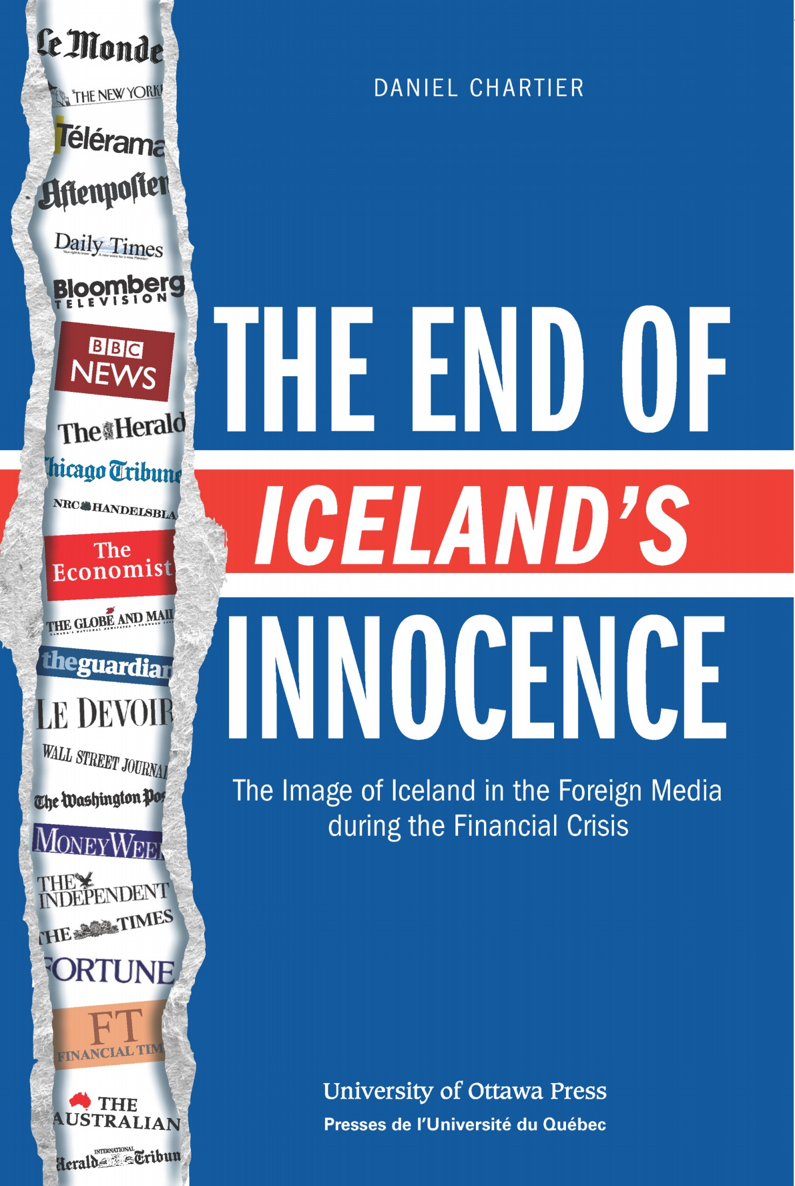

Until very recently, Iceland was known for its extraordinary landscapesmade up of volcanoes, geysers, glaciers, lava fields and deep fjordsand the rich cultural heritage left by descendants of the Vikings through the sagas. At the turn of the 21st century, this small country of 330,000 inhabitants surprised the West with its unprecedented economic growth, propelling it to the ranks of the richest nations on the planet. The short period of prosperity that ensued, during which the sky was the limit, constitutes Iceland's 'New Viking' period, a time referred to as such because the dozen businessmen behind the growth have been likened to the Vikings given their appetite for conquest.

Then, in late September 2008, the world witnessed the swift and spectacular fall of the empire built by these men, and the collapse of Iceland, which sank into a crisis that was first financial, then economic, moral and ethical in nature. And last but not least, Iceland is faced with an identity crisis. Within a few days, thousands of articles appeared in the foreign media, describing Iceland as bankrupt, the first casualty of a growing worldwide crisis, a country humiliated and ruined. The surprise was so great that the media could only wonder how a Western country could be hit by a crisis of that scope, as the following article appearing in Le Monde indicates:

Yes, how did it come to this? Iceland is not an emerging country; it's a very modern society of 330,000 inhabitants, the richest Nordic nation after Norway, ranking high in all the international indices. It is a constitutional state whose institutions are similar to those of the Scandinavian countries. And yet, it did come to this.

A number of assumptions were put forward in an attempt to explain the collapse of Iceland's economyinordinate borrowing by companies, banks and individuals; foreign conspiracy; collusion between political and economic powersbut one factor in particular was singled out: excess. Excessive confidence, excessive lack of restraint, excessive finance in light of the real economy. The economists observing the countrywhich could be described as a laboratory for neo liberalismwere able to foresee what would happen in a situation where value mechanisms, such as new rules for the production of wealth, were pushed to the limit. Before the collapse, borrowing opportunities seemed endless, and the profits were thought to be inevitable. All of Iceland's natural resources were suddenly in the role of collateral and to be exploited at once. As an adviser with the country's Chamber of Commerce said, 'Iceland has valuable resources in abundance, ranging from fish to clean energy and, as such, they can be leveraged for the good of the nation'.

With hindsight and historical perspective, there were signs warning of what was to comesigns that people seemed either unable or unwilling to heed in the frenzy of the economic boom. In 2006, Jeremy Batstone published an article in Money Week cautioning about the very situation Icelanders found themselves in a few months later:

Given the relatively small size of the country's economy, a sharp fall in GDP would feed its way quickly into the public finances. The budget surplus would be expected to turn swiftly into a deficit (as is the way with emerging economies). If the crisis widened to engulf the banking sector (although regional banks are vehemently denying any risk at present) the government would almost certainly end up having to shoulder a good part of the bank's increased debt burden.

In March 2008, David Ibison issued a warning in the Financial Times, stating that 'the country's banking assets have grown at a speed rarely seen in the modern world.... By 2006 they had risen to eight times GDP and the ratio is now thought to be near 10 times'.

What was foreseen actually occurred in autumn 2008: the entire New Viking empire collapsed in a few hours like a flimsy house of cards. Foreign journalists struggled to describe the scope of the crisis. Grard Lemarquis, for example, summarized the situation as follows, even before the crisis had reached a peak:

A potentially bankrupt country with its hand out to other countries for short-term financing, two of the three main banks urgently nationalised, 15% inflation, and a currency, the Icelandic krona, which has lost 60% of its value in one year: that is Iceland's present situation.

Then, an abundance of increasingly disastrous statistics began appearing in the foreign media: the Reykjavk exchange had lost 94% of its value; One hundred billion dollars of debt for 330,000 inhabitants, i.e., more than $300,000 for every man, woman and child in the country. As A.A. Gill wrote, that was a rude awakening for a country that a few months earlier was one of the richest nations in the world.

Today, beyond the statistics, the people of Iceland are angry and worried. The country, which had taken tremendous pride in its success, looked on powerlessly as its international image underwent a spectacular reversal. As Sarah O'Connor wrote in October 2008, 'the country's international reputation is ruined'. The story of this collapse, both fascinating and unsettling, is found in the narrative woven by the thousands of articles that appeared about Iceland in the foreign press during the crisis of 2008.

Sarah O'Connor, 'Glitnir chief rolls up her sleeves for mammoth task', Financial Times, October 19, 2008.

Grard Lemarquis, 'L'Islande au bord du gouffre', Le Monde, October 9, 2008, p. 3. The original quote read: 'Oui, comment en est-on arriv l? L'Islande n'est pas un pays en voie de dveloppement, c'est une socit trs moderne de 330 000 habitants, la plus riche des nations nordiques aprs la Norvge, qui caracole en tte de tous les palmars internationaux. C'est un tat de droit dont les institutions sont analogues celles des pays scandinaves. Et pourtant, on en est arriv l.'

Finnur Oddsson, quoted by David Ibison, 'Iceland wealth fund is proposed', Financial Times, April 25, 2008, p. 2.

A.A. Gill, 'Iceland: frozen assets', Sunday Times, December 14, 2008.

Jeremy Batstone, 'Is Iceland facing a meltdown?' Money Week, May 18, 2006.

David Ibison and Gillian Tett, 'Indignant Iceland faces a problem of perception' Financial Times, March 27, 2008, p. 13.

Grard Lemarquis, 'L'Islande au bord du gouffre', Le Monde, October 9, 2008, p. 3. The original quote read: 'Un pays en faillite potentielle mendiant l'tranger un financement court terme, deux des trois grandes banques nationalises en catastrophe, une inflation 15% et une monnaie, la couronne islandaise, qui, en un an, a perdu 60% de sa valeur : telle est la situation actuelle de l'Islande.'

Vincent Brousseau-Pouliot, 'Les gagnants et perdants d'une anne folle', La Presse (Montral), December 24, 2008.

IcelandReview.com, 'Default claims in Iceland pile up', January 13, 2009.

Eva Joly, 'L'Islande ou les faux semblants de la rgulation de l'aprs-crise', Le Monde, August 1, 2009. The original quote read: 'voit peser aujourd'hui sur ses paules 100 milliards de dollars de dettes, avec lesquelles l'immense majorit de sa population n'a strictement rien voir et dont elle n'a pas les moyens de s'acquitter'.