My aim in this book is to encourage you to use a small open boat to explore local and more distant waters. We will discover the amazing flexibility of a dinghy, small enough to be trailed behind a car and launched almost anywhere there is navigable water. A little boat, honed to her purpose, can carry you sure-footedly over the waves into the most beautiful and remote places.

Over the horizon

Loctudy has a melancholic end-of-season air. The caf-bar at the marina is closed, and its canvas canopies slat mournfully in the chill north-east wind. It is very late in the year for a sailing holiday, but I had a sudden whim to go cruising. Unlike most cabin yachts, my dinghy is not laid up ashore half the year, waiting to be craned back into the water in the spring. I am free to go sailing at any time I like. This means I can take advantage of the magical spells of settled weather that sometimes occur in late autumn, just before the onset of winter.

I scull my dinghy away from the slipway, hoist the lugsail and sheet in. The brown sail fills, her hull heels and she comes alive. Skirting the rows of white yachts sulking on their pontoons, I head towards the harbour mouth. The ebb tide sucks my boat swiftly into the narrows, and soon her bows rise to breast the rounded green swells of the Bay of Biscay beyond.

The local fishing fleet is returning to port. A flotilla of gaily-painted vessels plunges pugnaciously past me, a thicket of black flags flapping on the danbuoys racked in their sterns. A yellow arm waves from the last boat, and then vanishes back inside the wheelhouse. The fishing boat rounds a red beacon and enters the harbour. Very suddenly, I am alone. Avel Dro sails on towards the empty horizon.

The coastline astern becomes grey and less distinct, and eventually it begins to slide below the waves. The sail curves out over the seas to leeward, the sheet tugs at my hand and the tiller frets under my fingers. My boat lifts lightly to the swells and then swoops down into the troughs beyond. Occasionally a flurry of spray breaks over the weather bow. The only sounds are the scrunch of her bow wave and the murmur of the wake spreading out astern.

I have grown used to the loneliness of the open sea, and usually I find peace in its wide horizons. But the sea is not peaceful today. The long swells are dismal grey and ominously choppy. Avel Dro begins to sail hard-mouthed and slews into the wind in the gusts.

I stop to pull in a reef close to the rust-streaked east cardinal buoy protecting the isolated Men Dehou rock, 4 miles offshore. With sail lowered and the centreplate raised, Avel Dro lies stern to the wind, her buoyant transom lifting to the waves. I work in her heaving hull, rolling up the foot of the sail and tying the row of reef knots. The surly seas hiss past, cold and hostile.

A line of rocks leers above the horizon, like a row of stained and broken teeth my first sight of the islands. I wonder what desperate foolishness has brought me out onto this horrible waste so late in the day. Suddenly a sunbeam slips beneath the cloud wrack and lights up the distant archipelago. It glows golden like a promised land. My sail shines red and comforting in the low sun, and the seas no longer seem quite so threatening. I sail on with new hope.

Skirting the eastern side of the archipelago, I close with a wave-dashed west cardinal beacon rising from an offlying rock, which marks my chosen passage into the heart of the Glnan group. Hardening up the sail, I round the beacon and enter a long channel that cleaves into the heart of the archipelago. Waves break ominously on the rocks on both sides. Guided by the very dangers she must avoid, Avel Dro close-reaches into the jaw of the shoals.

The channel leads to a shallow passage between two long, low islands. Soon I can see the sandy bottom slipping past, close beneath my keel. Then the water deepens again and Avel Dro emerges into the main anchorage of the archipelago. An ancient castle towers sheer-faced from a tiny islet at its centre, reminding me that vessels flying the Red Ensign were not always so welcome in these waters.

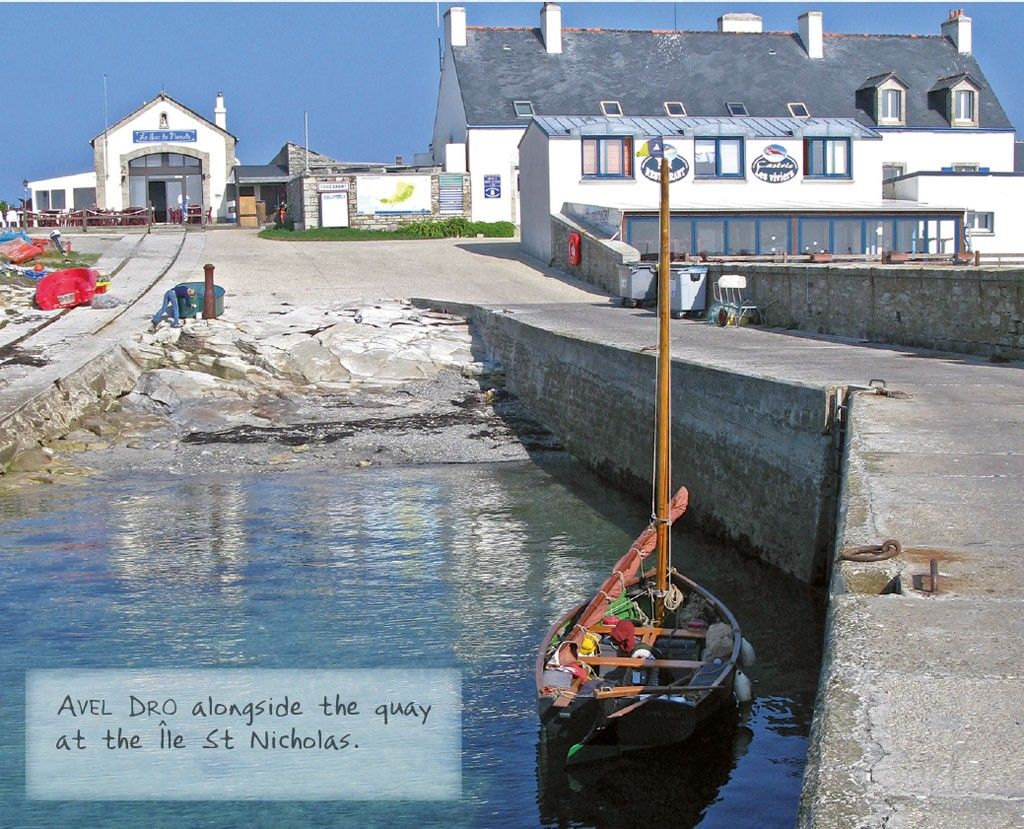

I bring my dinghy alongside the stone quay on the le St Nicholas and clamber up the iron ladder. There is no one about. The island appears to be all shut up for the winter. Eventually I find a small bar that is still open. There are only five people on the island it seems, and all of them are standing at the bar counter:

Were you on the vieux grement we saw sailing into the islands? they ask so respectfully you would have thought I had arrived in a windjammer, not a 15ft dinghy.

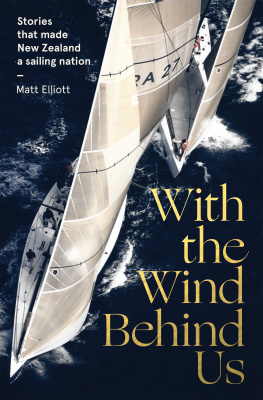

T HE GREAT WILDERNESS

A ncient and elemental, awesome in its power and vast beyond comprehension the sea is the last great wilderness of the world. The lives of most sea creatures still remain a mystery to us and we know less about the ocean depths than the surface of the Moon. Venture onto even the fringes of the wild ocean and it is impossible to remain unmoved or unchanged.

On land we inhabit an increasingly artificial environment. We enjoy the comforts of modern civilisation, but perhaps we feel that something has been lost. For why is it that so many of us take long aeroplane flights to distant lands, where life seems simpler and less artificial? It is as if we want to chase down the last remaining scraps of primitive authenticity before they too are lost, and in doing so we contribute to their inevitable destruction.

But real nature is more accessible than most people think. There is no need to cross the world to live simply in its wild embrace. Venture just two miles offshore and the land will start slipping into the sea, for that is how close the horizon appears when viewed from a small boat. Out on the wide ocean you can actually see the curvature of the Earth, bending away on all sides. No maritime culture has ever believed that the Earth was flat. Keep on sailing towards the far horizon, and soon you will be alone in a vast seascape, which has not changed over the whole span of human history. The waves still run, the gulls still swoop and glide, the breakers still wash the shores just as they did when our ancestors first built boats capable of navigating on open waters.

A fleet of Wayfarers rounds Old Harry rock near Swanage.

Beyond the shallows, punctuated by wind farms and navigation buoys, away from the production platforms rising from oil and gas fields, outside of the shipping lanes where the lines of cargo ships follow their well-trodden paths, the deep ocean remains profoundly empty. The sea still offers the promise of freedom and escape to anyone with the confidence to venture out upon it.

The wild ocean divides countries one from another, isolates offshore islands and consigns remote archipelagos to marginality or so it seems from the land. But the world looks quite different from a boat at sea. Out there, the sea is revealed as a unifying medium, linking coastlines and continents. The sea can be a savage place, but humanity has long since learnt how to navigate it with confidence. Ancient sea paths cross the waters of the world, the arteries of culture and trade since prehistory, rooted deep into the hinterland by rivers and canals. Water is the medium of civilisation. The great cities of the ancient world were always established on the coast or beside a navigable river. Sail a simple boat close along the shoreline, and you travel back to the very origins of human society.