Contents

Guide

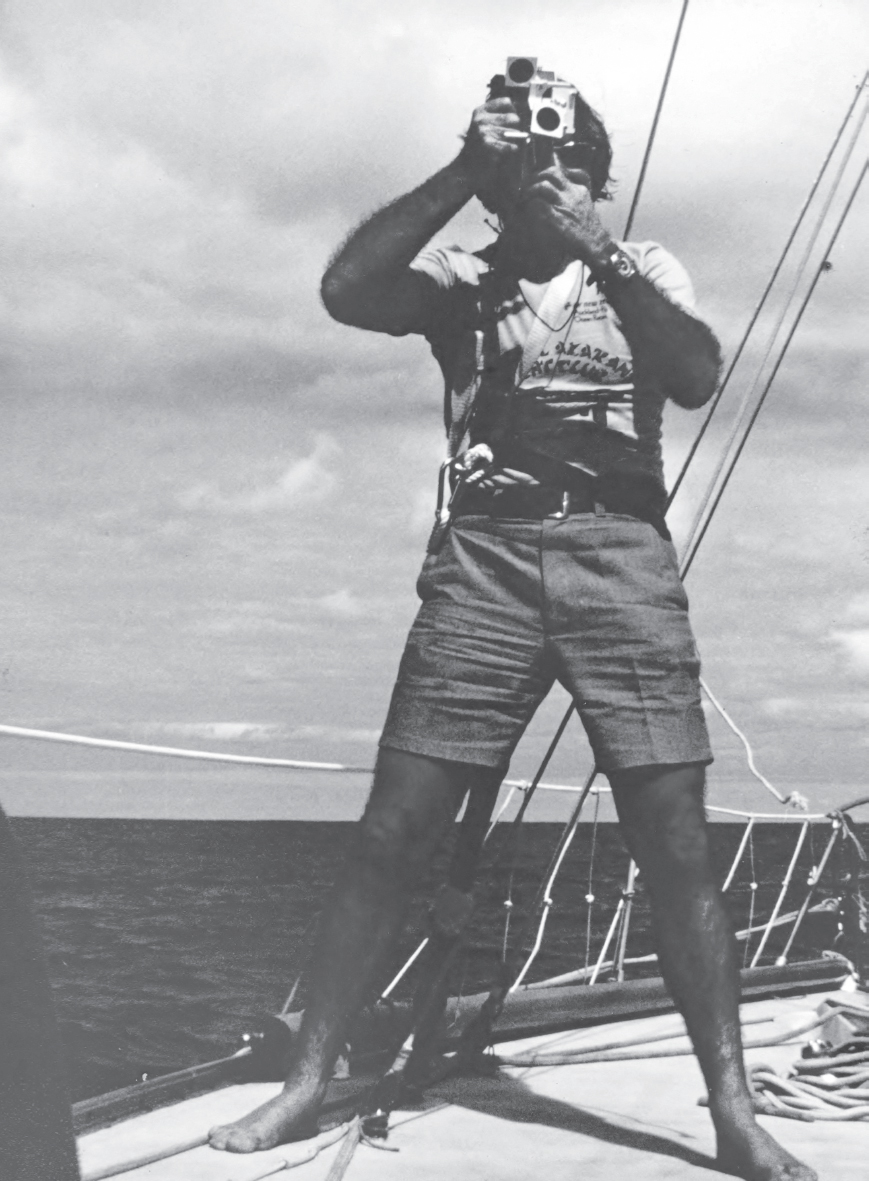

Dedicated to Ken Searle Naval Airman 2nd class, gum-digger,

skipper, navigator, environmentalist, home brewer and

much-loved family member

CONTENTS

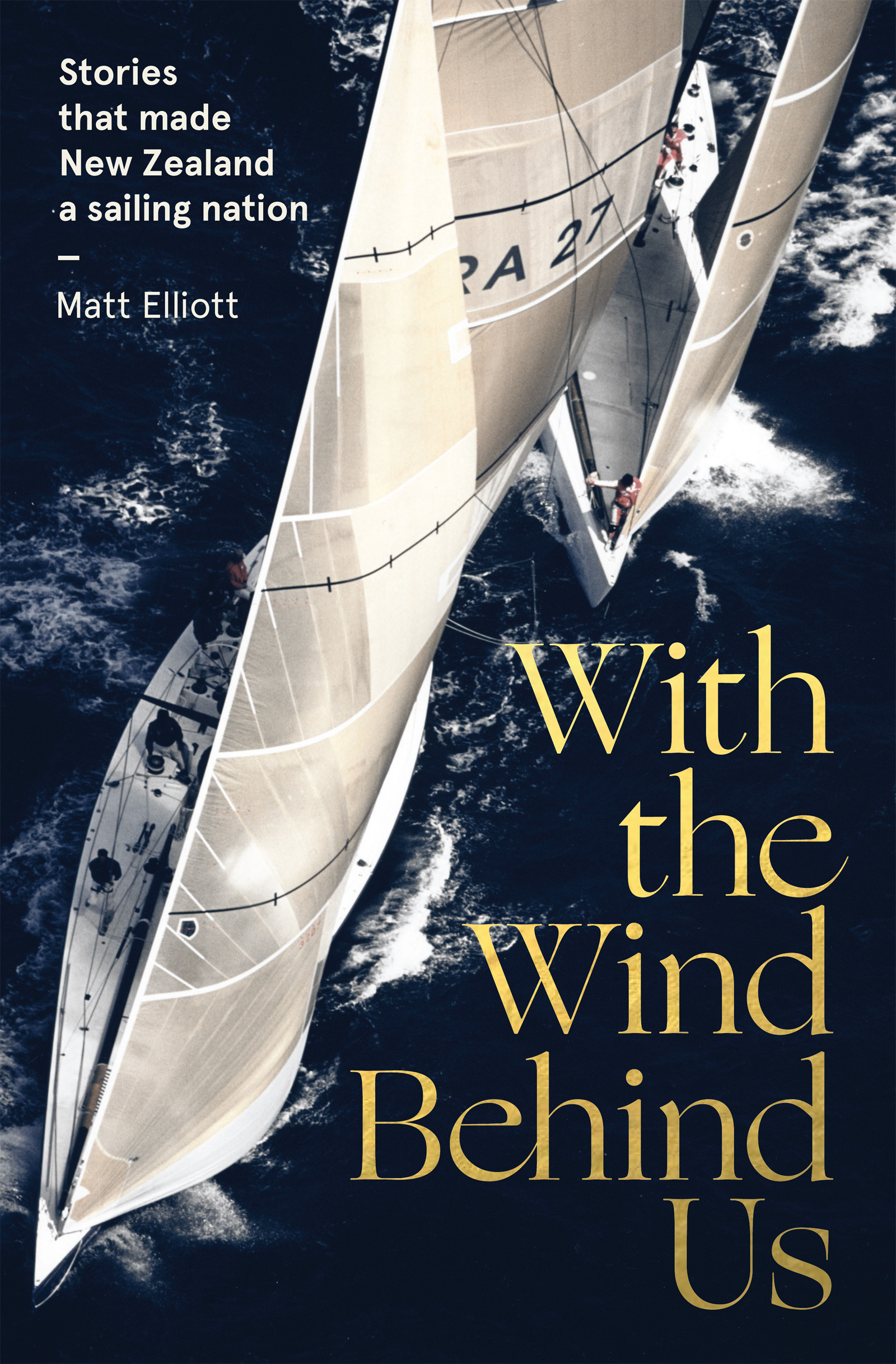

AFTER HIS FIRST EXPERIENCE of the Whitbread Round the World Race (now The Ocean Race) in 197374, Peter Blake famously declared that he would never do such a thing again. After competing in four more events, and winning the race in 198990, he finally stopped. Thats a famous example of the way in which someone can be drawn to the sea.

Our first Polynesian, and latter European, settlers all arrived under sail. The journeys were long, uncomfortable, arduous and not to everybodys liking. In my family there is the story of one group of family members crossing the Tasman to become resident in New Zealand. It was a particularly rough passage, and one of my grandfathers brothers moaned from his bunk, Sink, you bugger!

The sea has defined us as a nation. Along with the much-quoted statistic about New Zealand having x number of sheep per head of population, so have we become known for having more boats per head of population than any other country. Sailing was a necessary component of this countrys development economically, and was recreationally important, too. In the 1970s, when New Zealand-designed yachts and their sailors were becoming prominent on the world stage, it was very common to see car bumper-stickers that read, Id rather be sailing. From Aucklands Westhaven marina to isolated inlets and lakes, yachts can be spied all around this country. For some they can be a refuge, for others they are how you test yourself against others and the vagaries of Mother Nature and the sea.

While spending time in Cobh, on the southern coast of County Cork, Ireland, shortly after New Zealand had retained the Americas Cup in 2000, I went for a sail with a couple of local brothers. It was basically a nautical pub crawl between the taverns that sat at the waters edge around the harbour coastline. As the afternoon wore on, the brothers one the eldest in the family, the other the youngest became increasingly argumentative. The eldest, who owned the yacht, was at the stern, firing expletives at his sibling who wouldnt do what he was told. The mutinous brother stood at the bow, an angry figurehead, trying to ignore his brother and light a cigarette in the wind as he sang a chorus of swear words into the air. I was told to take over as helmsman: You Kiwis all know how to sail, just as you all know how to play feckin rugby.

The chapters in this book cover a range of topics related to how sailing has been and will always be very much part of the fabric of our society and culture, from the builders of some of the most impressive sailing ships this country has produced, to those whose small, accessible sailing dinghies introduced thousands of New Zealand children to the joys (and frustrations) of being on the water. Armed with skills learned on summer weekend race-days, some of those kids went on to become world champions in a variety of classes and events.

There are tales from the whaling days, first sightings of New Zealand, ghost ships, sea shanties, superstitions, and episodes of good fortune, drama and tragedy. There are mentions of sailors famous, infamous, unknown or long-forgotten. Adding to the folklore of the exploits of the German World War I mariner and pirate Count Felix von Luckner are extracts from a previously unpublished diary recounting an extraordinary tale of survival. There is also, for the first time, a lengthy recounting of the sinking of the yacht Snow White in 1979, telling what it is like to be in a liferaft hundreds of miles from land, waiting to be rescued events that, to paraphrase Blake, their participants wouldnt want to experience again, but wouldnt have missed for the world.

Haramai, e tama! E piki ki runga o Hikurangi, o Aorangi;

He ingoa ia no Hikurangi mai i Tawhiti, na o kau i tapa.

E huri to aroaro ki Prweranui, ki Tahumakakanui;

Ko te ara tna i whakaterea mai ai o tpuna

E te kauika tangaroa, te urunga tapu o Paikea,

Ka takoto i konei te ara moana ki Haruatai,

Ka tupea ki muri ko Taiwhakahuka,

Ka takoto te ara o Kahukura ki uta,

Ka tptia ki a Hinemkohurangi.

Ka patua i konei te ihinga moana, te wharenga moana;

Ka takiritia te takapau whakahaere,

Ka takoto i runga i a Hinekrito,

I a Hinekotea, i a Hinemkehu.

Ka whakapau te ngkau i konei ki te tuawhenua;

Ka rawe i te ingoa ko Aotearoa,

Ka tangi te mapu waiora i konei,

E tama, e i!

Come, O son, ascend the peaks of Hikurangi and Aorangi;

Tis a name from Hikurangi from Afar so called from your forbears

Turn you towards the Mighty northerly blast and the Great blistering easterly wind;

That was the course upon which your ancestors voyaged hither

Upon the deep sea school of whales, steered by the sacred ritual of Paikea,

Which becalmed the sea-ways upon the billowing ocean,

Leaving in their wake the flying sea spray,

Becalmed was the pathway of the Rainbow god to the shore,

Screened off by Hine the maid of the heavenly mist,

Subdued too were the billowing seas and curling waves;

The ritual of the voyage afar was chanted

and they rested upon Hine the maid with the tattooed buttocks

Hine the pale hued maid, Hine the maid with the golden hair

Pleasant thoughts were there of distant shore;

Sweet was the name of the long white cloud

And all hearts rejoiced with happiness

O Son, ah me!

Verse of a waiata among those compiled by

pirana Ngata for his 1927 book Ng Mteatea

LOOKING BACK NOW, it seems incredible, but when Russell Coutts (now Sir Russell) departed for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, as the New Zealand representative in the Finn class, few considered he had any chance of a medal. Certainly, his place at the Olympic regatta had been secured by winning the New Zealand trials, but Rick Dodson had been the form Kiwi sailor in the senior ranks over the previous few years, winning a world championship and the New Zealand nationals. Coutts was in the ascendant, though, having won gold at the world youth championships in the Laser in 1981.

The 22-year-olds first tacks in competitive sailing had taken place over a decade earlier at Paremata north of Wellington, winning the regional P-class championship. When Coutts was 11 years old the family moved south to Dunedin there, the family had a boat shed on the harbours edge and Coutts, who dreamed of sailing at the Olympics, took to the water whenever he could, often feistily racing his older brothers Robin and Grant.

Nationally, he became well-known as a youth sailor, a young man whose reputation would precede him. By the time he was at Otago Boys High School, Couttss heart was set on becoming a full-time sailor though just how that would manifest itself was a great unknown at a time when sailing was still a largely amateur recreation.

Couttss mathematical ability saw him accepted by the University of Auckland to study for an engineering degree. The move to Auckland in 1979 may have been a positive step in advancing his qualifications, but it also set him down in a city where yacht clubs were plentiful and the weather conditions allowed for more days on the water than in Dunedin. Studies quickly played second fiddle to sailing, with Coutts absent from the lecture halls for long periods as he chased success in local and international regattas. (It was 1986 before he finally graduated.)