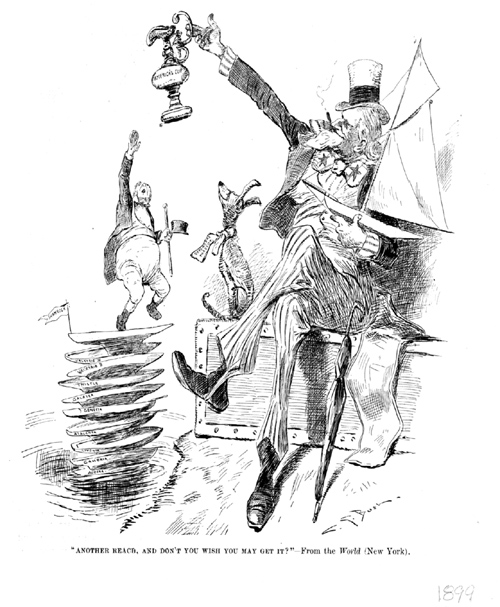

Uncle Sam teases John Bull with the Cup: Another reach, and dont you wish you may get it? New York World, 1899.

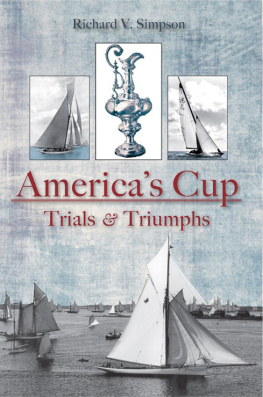

Richard V. Simpson

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2010 by Richard V. Simpson

All rights reserved

Front cover images: Top Center: An image of the celebrated cup as it appeared in 1905

Top Left: Herreshoffs Defender, page 85.

Top Right: British challenger the Sceptre, page 142.

Bottom: The New York Yacht Clubs 1888 Newport redezvous, page 27.

First published 2010

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.006.9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Simpson, Richard V.

The Americas Cup : trials and triumphs / Richard V. Simpson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition: ISBN 978-1-59629-329-8

1. Americas Cup--History. 2. Yacht racing--History. 3. Yachts--Design and construction--History. I. Title.

GV829.S56 2010

797.14--dc22

2010014132

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Foreword

The Race for the Americas Cup

Over the seas now for the twelfth time [1903], there has come a vessel in quest of the Americas Cup. While the first of the races for the cup will not be sailed on the Sandy Hook course until August twentieth, increasing interest has been shown for weeks past. The fact that three fast yachts are striving for the honor of defending the trophy has given stimulus to the interest this year. Sir Thomas Lipton, the central figure in all this yachting enthusiasm, has come besieging this year with a small navythe Shamrocks, I and II, each with a crew of over forty, the [steam] yacht Erin, manned by over half a hundred men, the sea-going tug Cruizer, and two American built launches. He has doggedly made this third expedition with his hundred and sixty seamen for a silver cup, twenty-seven inches high, which cost a hundred pounds. On this side of the Atlantic the preparations for defense has been quite as extensive. The challenge and defense of the Cup, first and last, will cost in the neighborhood of a million dollars.

This international excitement is in peculiar contrast to the interest shown fifty-two years ago, when the America defeated the flotilla of John Bulls fastest boats, and triumphantly brought the Cup back with it. Then, although the Yankee pilot-boat had won the first international yacht race with such apparent ease that there was no second, there were practically no press notices of the event in this country and the reception that greeted the schooner on its arrival was only mildly enthusiastic. It was eighteen years before any challenger for the Cup crossed the Atlantic. In 1870 Mr. James Ashburys Cambria sailed against an American flotilla of seventeen boats and was defeated by the Dauntless. Another Ashbury cutter, the Livonia, met defeat the following year, the Columbia and Sappho each out sailing her twice. Mr. Ashbury had very justly protested against the unfairness of having to sail against a whole flotilla. After much spirited correspondence he carried his point for the races of 1871, when he sailed against only one of our yachts at a time.

The Canadian challengers of 1876, and 1881 proved easy for the defenders. Then, in 1885 and 1886, came the Genesta and Galatea, which were in turn vanquished by the Boston sloops Mayflower and Puritan. The coming of the Scotch cutter Thistle in 1887, which was defeated by the Volunteer, was a much more important event than any one supposed at the time. It was then that Sir Thomas Lipton decided that his country, too, at some time, should have a yacht challenger. The history of the Valkyrie races of 1893 and 1895, and of the defeats of the two Shamrocks, everybody still remembers.

Years back, both challengers and defenders used to follow national lines pretty closely. The British boats were cutters, deep and narrow, with keelscraft especially suited to the deep, stormy, choppy British seas. The American vessels, on the other hand, were broad, shallow, center-board sloops, well adapted to our coast waters. From the time of the Puritan, however, there has been a constant game of give-and-take, of borrowing right and left, until today, to the unsophisticated, at least, Shamrock III and Reliance look a good deal alike. The Puritan was built somewhat on the lines of the British cutter. In 1887 the Volunteer showed British traits; while the Thistle, built for the specific purpose of speed in American waters, copied the broad American beam, and has been called the first British racing machine. In 1895 the center-board became a back numberit was hard, too, to give up such a hobbyand Herreshoff built the Defender with an orthodox John Bull keel. Both the Defender and Valkyrie were out-and-out racing machines, cut away below the water-line, and carrying large areas of sail, the American boat being a cutter in everything but the name.

International yacht racing of today unquestionably affords magnificent sport, and it has called forth remarkable ingenuity on the part of designers. Nevertheless, the present tendency in the construction of the ninety-footer is deplorable. The America, built fifty-two years ago, was one of those pilot-boats of which for speed and usefulness, the American seaman was justly proud. It cost something like thirty thousand dollars, and is a staunch, serviceable craft today. The Reliance, good authority has it, cost over three hundred thousand dollars, and will be good for nothing but old junk. As one New York paper put it, Herreshoffs latest monstrosity is a spardeck between a bulb of lead and an acre of sail. When in 1870, the Cambria came to this country as the first Cup challenger she raced James Gordon Bennetts Dauntless all the way across the Atlantic. The racer of today is such a delicate creature that it is really a great risk to let her get her feet wet.

What the next turn of the screw in the development of ocean racing machines will lead to is an open question. It is to be hoped that common sense will once more come to the front and that real boats will again be pressed into service.

Oliver Bronson Copen, The Race for the Americas Cup, Country Life in America, no. 4 (August 1903)

Authors Note