Published in the United States by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at Perseus Books, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special. markets@perseusbooks.com .

Names: Merali, Zeeya, author.

Title: A big bang in a little room : the quest to create new universes / Zeeya Merali.

Description: New York : Basic Books, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016036546 (print) | LCCN 2016040738 (ebook) | ISBN 9780465065912 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780465096619 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Cosmology.

Gods Billboard:

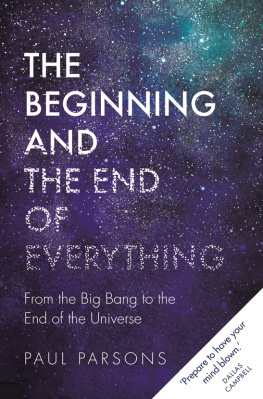

The Cosmic Microwave Background

T his is a book that is all about beginnings. It tells the story of the people uncovering the secrets of our universes birth, scientists who have spent decades striving to understand the origins of space, time, our cosmosand potentially many other parallel universes in an ever-inflating multiverse. Over the course of the following chapters, I will meet with them and others who argue that we could wield that knowledge to forge a new cosmos in the laboratory, with the help of some exotic physics, a few weird particles, a lot of energy, and a little bit of luck. And I will also be examining the ethics of whether or not we should perform such an act of creation, given the responsibility that comes with it. After all, once our baby was born, the theories say, it would evolve into a full-fledged universe, replete with new galaxies, new planets, and maybe even new life: a daughter civilization that would look upon us as gods.

So its somewhat ironic that the books beginning, this opening chapter of my journey, is starting off so badly.

Before committing to this (possibly quixotic) quest, I want to know if theres actually any point in entertaining the idea that we humans could become cosmic creators in our own right. Do any scientists believe we could truly make it happen?

In some sense, we cannot know for sure that we can make our own universe until weve done it. So I turn the question inside out: if we can, even in principle, knock together a baby universe, then it must stand to reason that our own cosmos might have been created by a more advanced civilization or superior intelligenceand we exist as proof of its success. If we could find evidence of that, it would be a huge discovery in its own right, reverberating through science and theology. And if our makers happened to leave any blueprints for how they performed this trick, so that we could repeat it, then all the better.

But does anybody, excluding science fiction authors, seriously think that the possibility that we could find signs of our alien makers (or, dare I say, a divine Maker, with a capital M) is plausible? And could we investigate this as a scientific, rather than metaphysical, hypothesis by searching for evidence? If so, then I think there is good reason to pursue this universe-building idea in depth.

The first person to ask, I decide, is Anthony Zee, a Chinese American physicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Zee not only has considered the possibility that the universe was made by an external intelligence but also has gone as far as calculating how to decipher any hidden communications scrawled across our cosmos fromas he and his co-author Stephen Hsu put it in their speculative paper around a decade agosome superior Being or Beings who got the universe going. Simply put, they figured out how to read the word of God, or that of our alien overlordsshould such an entity or entities exist and have chosen to message us, that isscribbled across the skies.

Figure 1: The cosmic microwave background is the radiation that filled the universe just 380,000 years after the big bang. This map shows slight variations in the temperature of this radiation across the sky. In this grayscale image, lighter regions are slightly warmer; darker regions are slightly colder. Credit: ESA and Planck Collaboration

The place to hunt for this code, they claimed back in 2006, is in the radiation that pervades the skythe cosmic microwave background, which is an echo of the big bang and would be the (hypothetical) creators chalk-board, as it were. Were immersed in this radiation bath, we pass through it every day, but were largely oblivious to it. Its worth taking the time in this chapter to come to grips with how this radiation came about because, aside from being a convenient place for a deity to leave us a memo, it also, less whimsically, serves as the strongest evidence of the big bang theory. And it turns out to be the best place to look for support for the model, which we shall meet later in the book, that provides the instruction manual for building our homemade universe.

I have traveled to Santa Barbara from London to meet with Zee, and I have a short list of questions to put to him about his paper with Hsu, tantalizingly titled Message in the Sky. Chief among them: is this a joke? That was actually my first reaction to the paper when it was released as a preprint back in 2005. Back then, my job as a reporter at New Scientist magazine was to find newsworthy research, and largely involved spending hours trawling through arXiv, the physics preprint server where physicists post new papers for the attention of the academic community, often at the same time as submitting them to a reputable journal, where the papers will be reviewed by their peers before publication.

But arXiv is a murky place, where goofy papers stand shoulder to shoulder with respectable workaday reports and, very occasionally, ground-breaking results. Knowing that these papers have yet to pass peer review and be officially sanctioned, you have to exercise a bit of care before choosing whether to cover one of them. Many never make it to journals.

The title initially made me worry that the paper was either a deliberate spoof or bad science. I quickly dismissed both of those concerns when I saw Zees name as an author, however. The physicist is a well-established senior researcher, with a long track record working out the kinds of things that would happen when you smash particles together in an accelerator, such as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), in Geneva, Switzerland (just the kind of place where some physicists hope that a new universe could be born, in fact). Zee is not a crank.

Reading further, I could see that the science that he and Hsu outlined, which well get into in detail a bit later, was also perfectly sensible. Still, at the time, I decided not to write a news article about it, partly because of the worry that it would be too oddball a topic to cover. But it had stuck in my mind ever since. What I really wanted to know back then, and what I still want to know today as I rap my knuckles on his office door, is what was the authors motivation for thinking about this question. In his core, does Zee honestly believe our universe was created by a God or gods, or aliens whose technological capabilities lie just beyond our ownand that we really could read off proof of this using experiments running today? Does that have bearing on whether he thinks we should carry out such a cosmos-making task ourselves? Or was the paper just an amusing example of an exercise all theoretical physicists revel in: asking fantastical what-if questions, just to see where they lead, without believing they could be literally true?