Pagebreaks of the print version

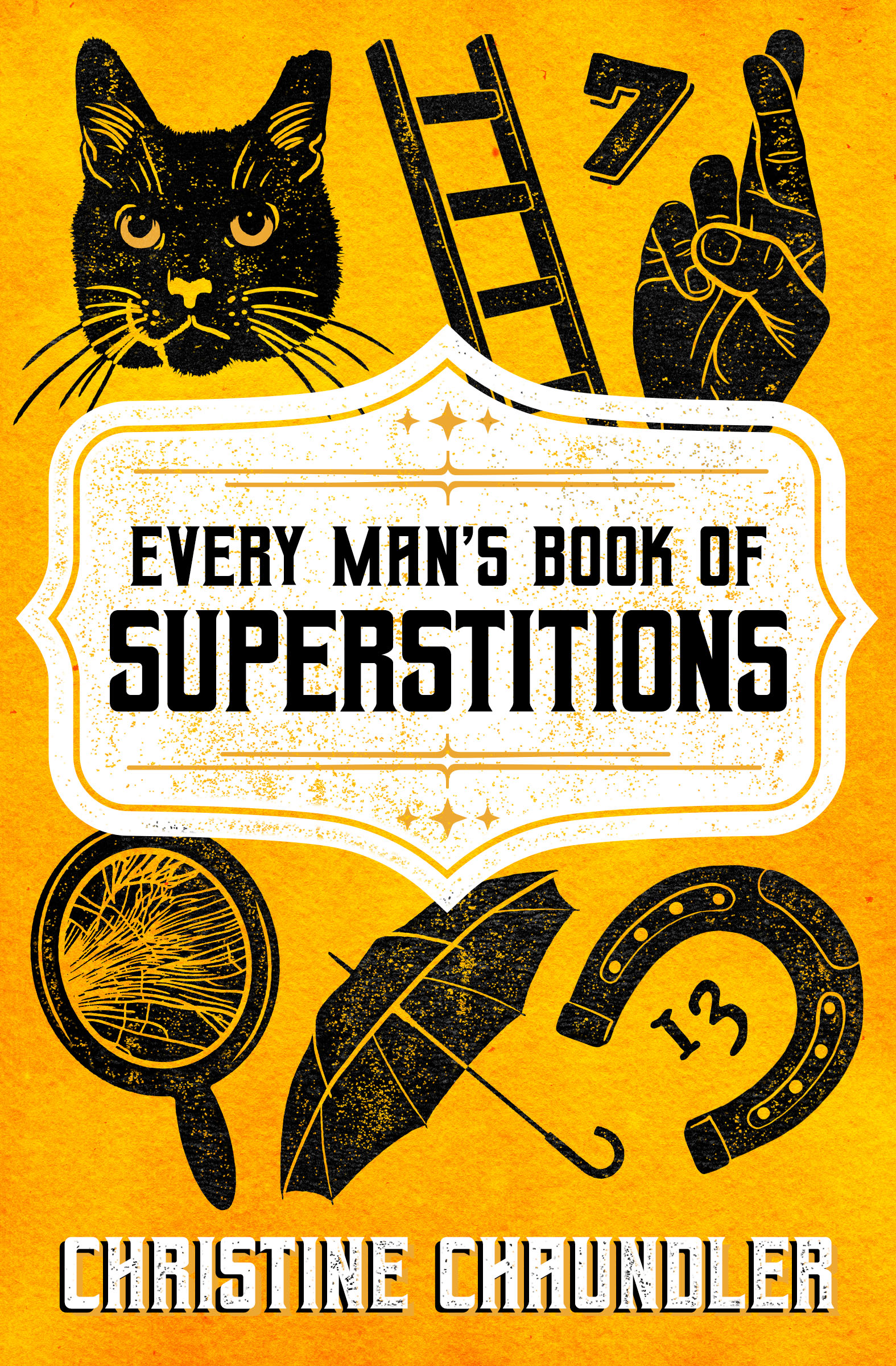

Every Mans Book of Superstitions

Christine Chaundler

Acknowledgments

My thanks are due to the following for their helpful suggestions: Mrs R. C. Allden, Mrs James Comyn, Miss Eileen Robinson, Mrs Hessell Tiltman, Septimus Newman Esq., Collin Rolls Esq.; also to The Librarian and Staff of the County Library, Chichester and the Proprietors of the Blackdown Bookshop, Haslemere, for their assistance in procuring books for me.

Introduction

Somebody got out of bed wrong foot first this morning!, said the Victorian nursemaid to her fretful charge. Now see you put your socks and shoes on the right one first, or well have you in trouble all day long!

The belief that it is important which foot is covered first when dressing is very ancient, and probably dates back to the days of ancient Rome. It is unlikely, though, that the nursemaid realised this when she rebuked the wailing child, nor, incidentally, that she may have occasioned it to adopt a lifetimes habit. Enquiry shows that most people clothe the right foot before the left one, probably adding that it seems to come naturally to do it in that way, not realising that in all likelihood they were taught to do so in their childhood, and that they are merely carrying on an ancient tradition whereby primitive man hoped to propitiate the beneficent deity whom he believed to have charge over the right side of his body. To attend to the left side first, ruled by a malevolent spirit, was asking for trouble.

Scholars tell us that many of the superstitions which to some extent are still in vogue to-day can be traced back to the worship of deities in whom men believed even before they bowed down to the gods of Olympus and Asgard, Babylon and Assyria. Some of them, it is thought, are relics of primitive fertility rites, such as those connected with the reaping of our British harvests. The practices are not really believed in now, even by those who, to be on the safe side as it were, still carry them out. But they were of great importance to the early inhabitants of the earth, as they are yet to native tribes in backward parts of the world. It is easy to see why. Early man found himself helpless in a hostile environment, vulnerable to all kinds of disasters which came to him from he knew not where. Flood and famine, extremes of heat and cold, lightning and thunder, sickness and death, descended upon him without warning. Where did they come from, and why? It seemed to him that he must be surrounded by superhuman beings, possessed of great powers for good or evil, and he must do what he could to conciliate them, to avert the harm they might do to him and persuade them to bring him good. Little by little, he and his fellow tribesmen evolved a system of religious rites and ceremonies which were handed down from generation to generation, changing gradually with the growth of civilisation and the enlightenment of the human mind. To-day, only vestiges of those ancient ceremonies, which once meant so much to our ancestors, survive in this country.

Yet survive they do, in spite of all that modern science and modern thought can do to banish them. Indeed, of recent years there seems to have been a revival here in Britain of some of the superstitious beliefs of the Middle Ages which, it might have been hoped, had quite disappeared. The rites of witchcraft are increasingly practised by some who think, or pretend to think, that they can acquire magical powers through getting in touch with the unseen by means of spells and incantations. One hears of covens of witches meeting on Walpurgis night, on Midsummers Eve, and Halloween, and rumours of dark, mysterious doings on moors and in lonely places. And the ancient cult of astrology has increased enormously, as can be seen by the fortune-telling columns in many of to-days magazines and newspapers.

Astrology may or may not be an exact science. Earnest practitioners of the art will tell you that it is, and certainly, when seriously pursued, it involves deep learning and calculation. The serious astrologers pour scorn upon the popular newspaper forecasts. They are, they tell you, based merely upon the time of year in which a man is born, the sign of the zodiac supposed to be prevalent at the moment when he comes into the world. The birth month is only one of the many things to be taken into account for the true casting of a horoscope. Apart from the sun, newspaper predictions take no notice of the positions of the stars, the aspects of the various planets, the ascendants, the Houses in which the heavenly bodies happen to be at the moment of birth, all these factors have to be studied and taken into account, a true astrologer declares, if an accurate delineation of the character and fortunes of any particular man is to be made. Fortunately for the peace of mind of the many people who look anxiously in their papers for news of what may be coming to them, these journalistic astrologers usually prophesy only favourable happenings in their prognostications of What the Stars Tell.

Astrology, of course, is a very ancient philosophy, and many of the superstitions we still cherish also go back far into the past. But there are others which, as far as one can see, must owe their origin to pure coincidence. A man carried out some action which was followed by disaster, or, perhaps, by some happy event. He did the same thing again with the same result. Was it due to what he did, or refrained from doing? He persuaded himself that it was, and thereafter avoided, or performed as the case might be, the thing which he believed had brought the bad or good result about. We can see this kind of superstition originating today, in the lucky objects many people like to carry about, the only difference being that primitive man attributed the magic in his talisman to some occult power, whereas the modern man or woman usually puts it down vaguely to luck.

People who really believe in their superstitions must have a rather unhappy time, though not quite such an unhappy one as they must have had in the past, when they imagined themselves to be surrounded by unseen beings all ready to do them evil, when everything they did, every word they uttered, seemed to them to be fraught with momentous consequences. Today, even the most credulous of us only half -believe in our pet superstitions. And though perhaps we may feel happier when we dont see the new moon through glass, spill the salt, or break a mirror, we are not, as a rule, terribly depressed when these accidents happen, and probably forget all about them in the course of a few hours.

The Dangers of the Day

The first thing to be done when we rise in the morning is to get out of bed, and here at once we find ourselves faced with a difficulty. If we want to be amiable and obliging during the day we must get out on the right side. From our earliest years it has been instilled into us that when we are cross and disagreeable we must have got out of bed on the wrong side. But which is the right side, and how are we to avoid leaving by the wrong one if our bed is pushed up against a wall so that we have no choice? Perhaps that is why our early mentors amended the dictum to that used most often todayYou must have got out of bed wrong foot first this morning.