Table of Contents

For God

For Country

and for Yale

... in that order

The Revolt Against the Establishment: God and Man at Yale at Fifty

by Austin W. Bramwell

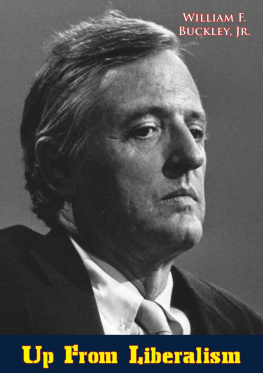

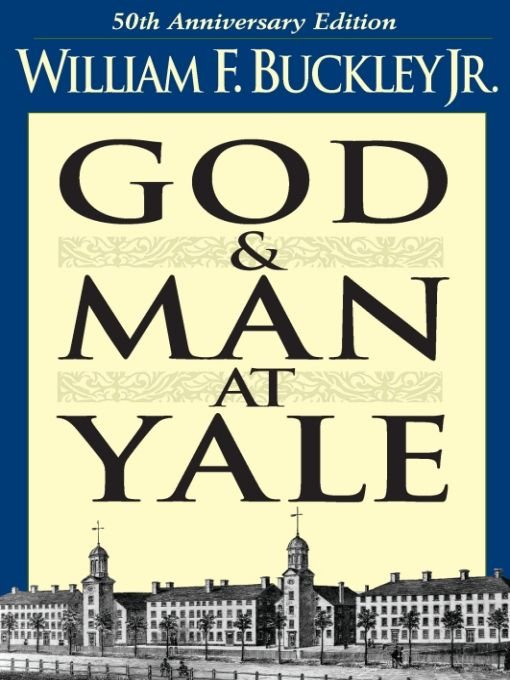

The year 2001 marked the golden anniversary of the publication of one of the seminal books in modern American conservatism, William F. Buckley Jr.s God and Man at Yale. Without it, one could fairly say, the conservative movement would not exist today. Soon after winning national attention with this controversial polemic, Buckley deployed his youth, charm, and intellect to unite a motley crew of cantankerous intellectuals into a viable conservative movement. Less than a generation after Lionel Trilling famously opined that in the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition, Buckley had in large part caused the liberal consensus to unravel.

For all its fame, however, God and Man at Yale is as noteworthy as a failure as it is as a success. Buckleys call for Yale alumni to withhold financial support until Yale ceased to undermine her students faith in Christianity and the free market went almost entirely unheeded; today Yale is more secular and left-wing than ever. Nonetheless, it would be a mistake to view the book as a mere historical artifact, for Buckleys tocsin rings as loudly today as it did then, and the controversy over the books argument is well worth revisiting.

So decisive has been the rout of Christianity at Yale that anyone under the age of fifty now can hardly imagine how Buckleys book could have caused as much controversy as it did, much less why Buckley should have become at the time the object of such intense vituperation. McGeorge Bundy called Buckley a violent, twisted, and ignorant young man, and questioned both the honesty of his method and the measure of his intelligence. Frank Ashburn, founder of the Brooks School, called him Torquemada, reincarnated in his early twenties, and insinuated that he should be wearing not academic robes but those of the Ku Klux Klan. Henry Sloane Coffin, the former president of Union Theological Seminary who chaired a blue-ribbon committee to respond to Buckleys charges, wrote snidely that Buckley, a Roman Catholic, should have attended Fordham or some similar [Catholic] institution.

If these attacks seem personal, that is because they were. All of the major players in the effort to discredit Buckley hailed from old-line Yale families. Many of them, including Coffin, Bundy, and Ashburn, belonged (like Buckley himself) to Skull and Bones. Charles Seymour, the president of Yale while Buckley was an undergraduate, was himself a Bonesman, while A. Whitney Griswold, the Yale president when the book was published, came from a Bones family. Buckleys attackers thus saw themselves as custodians of a great tradition; their religion was liberal Protestant, their outlook modern, and their sensibility elitist. To them, Roman Catholicism, like Evangelical Protestantism, was the religion of the lower classespublicly tolerated but privately derided. Buckley in consequence was not so much a Torquemada as a latter-day Alaric who, upon being invited into the very citadel of northeastern WASP prestige, had the gaucherie to question its continued legitimacy.

Part of the difficulty in understanding the controversy over God and Man at Yale is that the class distinctions that made Buckley such an unwelcome guest have become blurred since the 1960s. Students today associate religious conservatism with Establishment stuffiness, whereas in truth the leaders of the American Establishment at mid-century contemned both religious enthusiasm and religious orthodoxy. To be sure, the social prestige of men such as Bundy and Coffin could only exist within a Christian society whose mainline churches dominated the universities, and in turn, the government and the culture. Ironically, had the old Yale scions only followed Buckleys prescriptions, they might not have seen their regime crumble around them in the 1960s. Perhaps an even greater irony is that Buckleys urbanity and charm have made him perhaps the last living icon of the traditional high-WASP temperament.

In 1951, however, he was but a barbarian who had somehow found his way into the inner temple. His arguments in God and Man at Yale were straightforward: first, Yale was undermining students faith in Christianity; second, Yale was promoting economic collectivism; and third, alumni should exert their influence to reverse the course of pedagogy at Yale. His critics refused, however, to take these points at face value, but rather insisted that the book was not what it seemed. Fulminated Ashburn, [God and Man at Yale] stands as one of the most forthright, implacable, typical, and unscrupulously sincere examples of a return to authoritarianism that has appeared. Under the guise of liberty it attacks freedom; under the guise of knowledge it denies the privilege of free investigation and dissent; under the guise of defending capitalism and religion it uses the technique of Dr. Goebbels; under the guise of academic freedom it hides the somber robes of theocracy.

How did a book about pedagogy at Yale inspire a philippic against totalitarianism? Ashburn was not alone in leveling such charges at Buckley; every one of his critics construed the book as an attack not only on Yale, but also, despite Buckleys professed belief in democracy and freedom, as a veiled attack on the very nature of a free society. Certainly they could not have inferred this insidious purpose from the substance of Buckleys arguments. In reaching the books first two conclusions, Buckley was scrupulous almost to a fault in examining Yale department by department, professor by professor, in order to assess the effect each was having on students spiritual lives and political convictions. Indeed, much of the debate over the book focused not so much on questions of fact but on questions of interpretation. Buckley found that the drift of Keynesian economics was collectivist; his critics insisted that Lord Keynes merely defended the free market from itself. Buckley presupposed that Christianity entailed adherence to the orthodox tenets of the faith; his critics thought that mere interest in Christian spirituality sufficed to demonstrate the strength of religion on campus. Although in each case Buckley upheld the more rigorous view, the differences were surely not so great as to put him in the camp of Dr. Goebbels.

God and Man at Yales third chargethat alumni should exercise control over the teaching at Yalewas more controversial still. Buckley deconstructed the idea of academic freedom from two angles. First, pure academic freedom was a mirage, he claimed, for Yale would (quite rightly) never allow an anthropologist to teach theories of Aryan racial superiority. Thus, the question was not whether academic freedom should be restricted, but to what extent. Second, romantic notions to the contrary notwithstanding, truth does not always win out in the free marketplace of ideas. Both Italy and Germany, Buckley observed, had the option to elect democratic leaders or authoritarians, but both chose the latter rather than the former. If we indeed know that democracy is superior to totalitarianism, then we have a duty to defend and advance this truth rather than to maintain a falsely open question. In sum, Buckley argued, Yale should restrict academic freedom such that Christianity and political freedom always upheld.