Table of Contents

PRAISE FOR

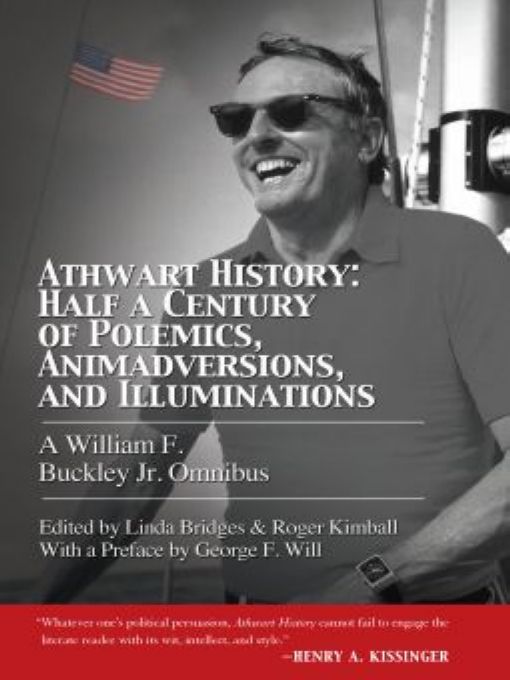

Athwart History: Half a Century of Polemics, Animadversions, and Illuminations

For nearly sixty years, Bill Buckley was a fixture on the American public scene. Or rather, not a fixture, but a presence in constant motion, darting from editorial office to television studio to college campus, to spread the word about what made America great and why the Western tradition was worth defending at all costs. Bill is no longer with us, but in this splendid collection we have a lifetimes worth of his penetrating analysis, profound moral understanding, and, always, the leavening wit. Chosen from the millions of words he wrote, the pieces offered here deal with subjects ranging from the immorality of deficit spending to the glories of J. S. Bach; from the refreshing candor of Barry Goldwater to Senator Kennedys unconscionable description of Robert Borks America. If you love Bill Buckley, youll need Athwart History, which includes dozens of pieces that have never before appeared between hard covers. If you dont yet know him, be prepared for a dazzling ride through postwar America and the world.

Rush Limbaugh

I didnt think anything could make me miss Bill Buckley more than I already did, but reading the columns and essays collected in Athwart History turned the trick. Has there ever been a better intellectual short hitter? This book is a priceless reminder of the days when his sharp wit, remorseless logic, and preternaturally acute moral imagination made the op-ed pages of America vastly more entertainingand infinitely less predictable.

Terry Teachout, author of The Skeptic: A Life of H. L. Mencken

Bill Buckley has achieved icon statusrichly deserved, of course. But in placing him on a plinth, we may have forgotten what a cut- and-thrust combatant he was, and what a warm and loving friend. Through this beautifully assembled compilation, we get the uncut Buckley, and rediscover whence conservatism got its elanand its spine.

Mona Charen, syndicated columnist with Creators Syndicate

PREFACE

George F. Will

The most important intellectual development of the nineteenth century was that history became Historya proper noun. Hitherto it had been the narrative of the human story, sometimes grand and inspiriting, sometimes mundane, sometimes seemingly a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. But always history had been understood as a drama driven by human choices, with perhaps an occasional intervention from God, or the gods.

Then came the nineteenth centurys invention of historicism. The idea has had many advocates and manifestations, but one man made it a world-shaking fixation, especially for intellectuals. Karl Marx argued that there are iron laws that govern the unfolding of history, driving it to a destination that can be known, and hastened, by the discerning few, who deserve to be the leaders of the undiscerning. Those who lack the key of theory cannot unlock Historys secret. They are unable to pierce the veil of mere appearance. They are in the grip of false consciousness. Although they fancy themselves the masters of their fate, they are actually mere play-things of events, a.k.a. History.

The most important intellectual event of the twentieth century was the revolt against the idea that vast, impersonal forces make a mockery of the illusion that we make meaningful choices about how we shall live. Those who led this uprising in defense of lifes moral seriousness decided to stand athwart historymake that Historyand tell it to stop thinking that it is at the wheel of the world. And that is why what William F. Buckley Jr. did five years after midcentury mattered so much.

When he, in effect, rolled up that first copy of National Review and swatted History on its upturned nose, he was saying: You are not all that you have been cracked up to be. Yes, Buckley said, there are political tendencies, and very strong ones, in Western societies. But tendencies tend to be resistible, so let the resistance begin.

And let it begin with the high spirits and sense of fun that should accompany a quickened sense that humanity has emancipated itself from fear of all determinisms. If there is a common thread in Buckleys writings, it is the compatibility of seriousness, even occasional indignation, with an unfailing sense of merriment about the pleasures of intellectual combat.

One of Buckleys first tasks, however, was to convert conservatism from a mere sensibility and a literary phenomenon into a political force. For that, he needed a horse to ride. Appropriately, he found one in cowboy country.

Arizonas junior senator, Barry Goldwater, was, in the felicitous phrase of Richard Rovere, a commentator prominent in the 1950s and 1960s, a cheerful malcontent. He was not an intellectual, but he knew that politics without the ballast of ideas is a lighter-than-air balloon that will be blown about by gusts of wind. Goldwaters 1964 presidential campaign was, as the title of a book on it declared, a magnificent catastrophe. But it was catastrophic only in the short run and only because he lost forty-four states. It was magnificent because it was an insurrection against the conventional wisdom about the narrow limits within which political debate supposedly had to take place.

Sixteen years later, the seeds sown by Goldwaters candidacy came to fruition, making possibleno, mandatorythe following conclusion: Buckley was Americas political Johnny Appleseed. Without Buckley, there would have been no National Review; without NR, there would have been no coming into existence, and coming together, of the forces that captured the Republican Party and nominated Goldwater. Without that nomination, the presidency of Ronald Reagan probably would not have happened. Therefore, Buckley was the most consequential political controversialist since Thomas Paine.

Buckley was, of course, much more than that, because his tastes and interests were so catholic. Yes, the pun is intended.

Actually, it sometimes seemed that Buckley considered conducting political arguments, narrowly understood, a duty to be done in order to gather a readership for other, more interesting and often more important subjects, such as the health of the culture and of the religious impulse that must, Buckley thought, sustain any durable and defensible culture. But politics, broadly and properly understood, concerns how humanity should live in its social dimension. Which means it concerns everything. So, although it might have mortified him to think so, Buckley really was merelymerely!a political commentator, even when he wandered far afield from the mundane matters of elections and stuff.

Those elections that once seemed so momentous have now receded from memory, and we can now see what made Buckley such a history-making figure: He helped to unmake History, thereby reviving history as a truly human drama. He asserted, and then proved, that a few determined men and women, equipped with sound ideas, could put paid to all ideas of determinism. They could choose to command history to halt, step back, and turn right.

It did. It had no choice.

INTRODUCTION

Roger Kimball

Of making many books, we read in Ecclesiastes, there is no end. I do not believe that sage found the prospect cheering, either. But for William F. Buckley Jr., the making of many books was an ineluctable part of life. He started young, in his mid-twenties, with