CONTENTS

Guide

W hittaker Chambers once told William F. Buckley Jr. that a scenic view from ones desk is the great enemy of productivity. This sentiment may seem excessively Spartan, but there is something to it. My best moments at the keyboard occur in the dead of night, when most people are asleep, incoming email slows to a trickle, and there are no distractions out the pitch-black window. I know others who feel a similar connection with the early morning hours. These are moments when one has the impression of solitude. It is only an impression, though, because the solitary writer, or at least this solitary writer, ultimately produces work that depends on interactionssocial, professional, intellectualwith so many others. And now is my chance to express my gratitude to those others.

Many thanks to the staffs of the Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library, the Manuscripts & Archives collection at Yale Universitys Sterling Memorial Library, and Harvard Universitys Schlesinger Library. Spencer DeVilbiss, at Utah State Universitys Merrill-Cazier Library, went above and beyond the call of duty in gaining me access to a few Firing Line rarities. Nancy Rose and Ron Basich came to my rescue with technical assistance, and, at the very end, Erik Stayton tweaked and formatted the manuscript over the finish line with patience and acumen. I owe a particular debt to the staff of the Hoover Institution, especially the ever-vigilant and helpful Rachel Bauer. Rachels assistance was absolutely invaluable to this project. How amazing, during the Boston Snowpocalypse of 2015, to have an ally determined that my precious Firing Line DVDs from Stanford would somehow arrive on my doorstep in Cambridge. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology provided generous funding for research and, especially, technical assistance toward the end, and my MIT colleagues and students in Comparative Media Studies/Writing have also been tremendously supportive. How lucky I am to have found a professional home where people laugh (politely?) at my Star Trek jokes.

For their time and insights, I am most grateful to those whom I interviewed for this book: Linda Bridges, Richard Brookhiser, Christopher Buckley, Lawrence Chickerling, Agatha Dowd, Neal Freeman, Ira Glasser, Mark Green, Jeff Greenfield, Michael Kinsley, Rich Lowry, Newton Minow, and Victor Navasky. Also, John Judis very kindly shared several unpublished interviews with me.

Chris Calhoun and Adam Bellow were terrifically gung ho about the project and were a pleasure to work with. Several folks were kind enough to read the work as it moved along, or to otherwise provide inspiration and/or intellectual support: Henri Cole, Donald Crafton, Beverly Gage, Pupa Gilbert, Elyse Graham, David Greenberg, Patrick Keating, Kevin Kruse, Diane McWhorter, Ben Miller, Erin Lee Mock, Susan Moffitt, Francesca Rossi, Casey Rothschild (thanks for explaining about Laffer and his napkin!), Meghan ORourke, Susan Ohmer, ZZ Packer, Mauricio Pauly, Leona Sampson, Carol Steiker, John Tasioulas, Itai Yanai, and Clark Williams. Jonathan Kirshner had total confidence in the book before anyone else, even me.

The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study offered a most gracious and supportive home in which to advance the project in 201415. There, record shindigs, Rob Roys, intellectual companionship, group dinners, movie nights, and congealed baked brie somehow all came together as the dilithium crystals that powered my warp drive. I shall always treasure my year at Radcliffe.

Buckley once (well, probably more than once) declared that industry is the enemy of melancholy. True enough, but one needs comrades as well. I owe much to the friends who in various ways saw me through the challenging days of 201213: Barbara Abrash, Josh Berman, Mark Betz, Andrea Buffa, Eric Freedman, Mary Fuller, Amy Herzog, Harry Holtzman, Barb Klinger, Julie Lavelle, Lynn Love, Kevin Maher, Allison McCracken, D. N. Rodowick, Sallyann Roth, David Smith, and Buffy Summers.

Finally, my pinball wizard, Mauricio Cordero, provided light, momentum, dance breaks, pizza, martinis, and inspiration. How do you think he does it? I dont know! What makes him so good?

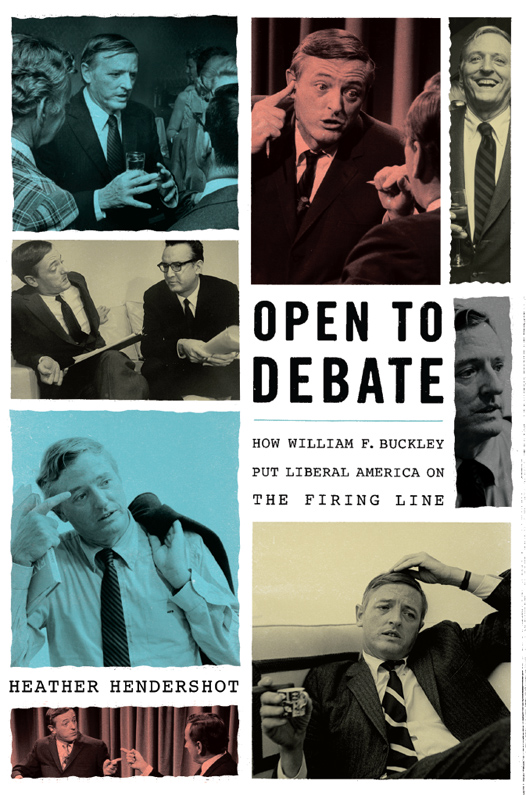

I n 1951, William F. Buckley Jr. wrote a book with the weighty title God and Man at Yale: On the Superstitions of Academic Freedom. There was no reason to expect the book to be a great hit. It had been released by Regnery, a small conservative publisher. If practically no one had heard of Regneryit was one of only three conservative American presses, and it was hardly thrivingabsolutely no one had heard of Buckley. He was just a twenty-six-year-old kid from a wealthy Connecticut family that had made and lost a fortune in Mexican oil, then made a second fortune in the oilfields of Venezuela. In 1955 Buckley would found Americas preeminent journal of conservative opinion, and in 1966 he would found Americas longest-running conservative public affairs television program. He would, in short, become a public intellectual, a political movement builder, and a TV star. But in 1951 he was still an unknown quantity.

Buckley was whip-smart, and he had a lot of nerve. At the age of six, he had written a letter to the king of England demanding that the country pay the debt it owed to the United States from the Great War. Buckley had served in World War II, excelled on the Yale debate team, and edited the Yale Daily News. He was an accomplished young man, but with his erudite vocabulary, aristocratic manner, and archconservative politics, few in 1951 would have pegged him as an up-and-coming celebrity. In the wake of almost twenty years of New Deal liberalism, conservatism barely had a pulse. Why should anyone notice this brash young man?

In God and Man at Yale, Buckley laid into his alma mater for its secular humanism and, to his mind, its professors rabid support of the New Deal, the Fair Deal, and liberal encroachments on the free market. The book would prove a minor sensation, in part because Yale went out of its way to alert everyone that they really should not read it. Perhaps out of a patrician sense of decorum, Buckley had allowed Yale president Whitney Griswold to see the manuscript in advance of publication. Soon after, a wealthy alumnus phoned Buckley to tell him that Yale was taking care of some of the professors Buckley had attacked and that there was really no longer a need for the book.

Needless to say, Buckley thought this was stuff and nonsense. Griswold rather dubiously told concerned alumni who got in touch with him that the book was the product of Buckleys militant Catholicism. Yale graduate and Harvard professor McGeorge Bundy wrote a scathing review in the Atlantic, having first discussed the reviews major points with Griswold. Bundy attacked Buckleys arguments as ill-founded and also noted that he had no purchase as a Catholic to attack an essentially Protestant institution. This burning criticism was topped off with a range of positive and negative reviews, an introduction by the reputable journalist John Chamberlain, and Buckley Sr.s subsidizing of a book tour for his sonit all spelled success for the book.

The initial print run of God and Man at Yale in October 1951 had been 5,000. The book quickly sold 12,000 copies. The bestselling nonfiction books of 1951 and 1952 included Rachel Carsons environmentalist The Sea Around Us; Jack Lait and Lee Mortimers muckraking Washington Confidential; Mr. President, a collection of Harry Trumans papers and diaries; Witness by Whittaker Chambers; and Tallulah Bankheads autobiography. Buckleys book edged in at number sixteen in November 1951. Not bad for a first book, written by a twenty-six-year-old, published by what was then a nothing press.