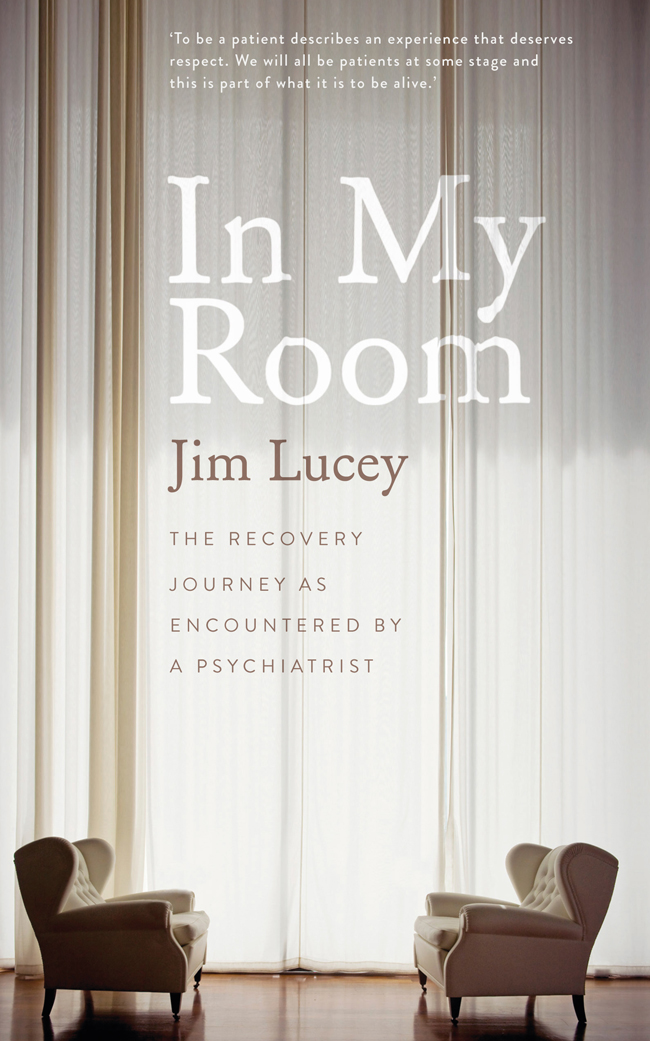

In My Room

The recovery journey as encountered by a

psychiatrist

Jim Lucey

Gill & Macmillan

Contents

A lively understandable spirit |

Once entertained you. |

It will come again. |

Be still. |

Wait. |

THEODORE ROETHKE |

Introduction

T his book goes some way towards describing my clinical practice. I have done this in the hope that it might demystify the hidden zone that exists between the psychiatrist and the patient, and illuminate in part the journey some people take to mental health and recovery. I have chosen the method of clinical storytelling. Wherever I have included an account it is intended to illustrate a human issue that is derived from a real professional experience. This is not a representative textbook of psychiatry or a manual for self-help, neither is it a comprehensive description of mental health care in Ireland. It is intended for the general reader, as an authentic description of the journey from distress to recovery as I have witnessed it.

My understanding of recovery has grown over many years and reflects many influences and experiences. Prominent amongst these influences is the education that I have received from my patients. Of course a therapeutic professional is required to put away any personal agendas, for fear of subjectively distorting the patients recovery. A psychiatrist tries to concentrate objectively, but for the purpose of this book it would have been one-sided to include only the observations of my patients journeys and to completely exclude reference to my own projections. In an authentic description of clinical practice, occasional revelation of the clinicians therapeutic position is informative. This therapy is not rooted in a blank canvas. In order to achieve a balanced description of the reciprocal doctor patient relationships, I have referenced some of my thoughts and countertransferences whenever it seemed helpful.

Throughout the book, I have made some references to the standard diagnostic schedule produced by the World Health Organization (WHO) and known as the ICD-10 or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision. The selected passages are objective agreed descriptors of clinical disorders and their use is part of the standard methodology of psychiatric practice. In psychiatry, diagnosis is not based upon any specific blood test or screen. No such tool exists in mental health care. Categorical diagnosis is useful, and is traditionally seen as a necessary and reliable function within medicine but it is not sufficient by itself. The diagnoses provide a useful starting point but they are not the full picture, and they may change. What is important is an individual care plan, since people present with varied features of mental distress and some have a mental disorder. Even if diagnostic criteria are met for a particular disorder, two people with the very same diagnostic description can have quite different problems with different severity and distinctive complexity. The recognition of complexity necessitates individual care planning and underpins the person-centred approach to recovery that is the basis of effective care.

All of the recovery stories in this collection are authentic. While they are real (otherwise they would be of no value), the details have been amalgamated and specific identifiers have been altered. Ireland is a small country and it is important to protect the anonymity of anyone who seeks mental health care. It would be wrong to expose those from whom we hope to learn. Over the years, I have always sought the permission of those whose stories I have adapted for teaching (or more recently for broadcasting) and this is true for all the accounts included here. That being said, no character in this volume represents any single private individual, so I wish to assure the reader: anyone who perceives a resemblance to a particular person is mistaken.

There are many reasons why I have included poetry in this book, the most valid being the fact that I regularly use these poems in my own practice. Many of us find it difficult to speak of the mind, and a poem can help to capture a lived experience, adding to it the elusive language of personal reflection, feelings, thoughts and insights. For some of us, an entirely new form of communication is necessary and poetry can be a useful way of introducing this less tangible vocabulary. Mental health care requires an ability to listen and to reflect. Hopefully these poems will provide illustrations of this thoughtful communication and will also provide a way to convey to the reader still unfamiliar with mental health care the ambiguous emotional intensity of a therapeutic relationship.

The heroes of these stories are referred to consistently using the term patient rather than any other descriptor, such as service user or client. In order to avoid being unwieldy, and without striving to be politically correct, it seemed best to stay with a language more familiar to a doctor. Over the past thirty years, my patients have taught me more than can be said and I am very grateful to them. And so the term patient is used as a humane acknowledgement and a universal term signifying one of us who is suffering. To be a patient describes an experience that deserves respect. We will all be patients at some stage and this is part of what it is to be alive.

The Room

M y room at St Patricks University Hospital has a high ceiling, a wooden desk, a bookcase and a number of comfortable soft chairs. To the left of the desk, a tall window looks north to a quiet garden. Beneath the window there is a small side table with bottles of drinking water and some cups. The room is warm and the furniture is reassuringly familiar to me.

The room does not have the iconic psychiatrists couch. Amongst some books and papers on the desk, there is a computer, a reading lamp and a box of tissues. The floor is covered with a carpet and in front of the desk there is a small rug. In another corner of the room there are two large filing cabinets. A few colourful prints hang on the walls alongside some certificates of qualification. There are many other idiosyncratic bits and pieces; some with personal significance and others with none. There are photos on the bookshelves and toy cars sitting on the desk, as well as some shortbread biscuits, a teapot and a kettle on the side table. There are many books on mental health and history.

Of course, in many ways, none of this really matters. This room could be more or less formal, personal or spartan, but so long as it is a space where people feel able to talk, and feel that someone has listened and heard them, then it is a space of value.

When people come to the room for the first time they are likely to be very apprehensive. Many do not know what to expect. Some may anticipate the dramatic portrayal of mental health assessment seen in popular media such as The Sopranos or Analyse This. The reality of the psychiatric clinic may turn out to be more prosaic than expected.

Mental health assessment takes more than the right physical setting or the right location. It is hard to define what makes an assessment work, and even harder to ensure that these elements are in place all of the time. In this regard it is helpful to recall the views of Patricia, an especially wise and forthright recovered patient with a capacity for directness. She explained: The physical environment for therapy and its quality does matter, of course, but not very much. When you are in distress its the quality of the care that counts. If you stick the wrong people in the right office, all you achieve is a nightmare outcome in a nice environment. When I was on the ledge, in the depths of my depression, the most important environmental factors were the ones that empowered me to talk, to feel that someone had listened to me, heard me, and given me hope.