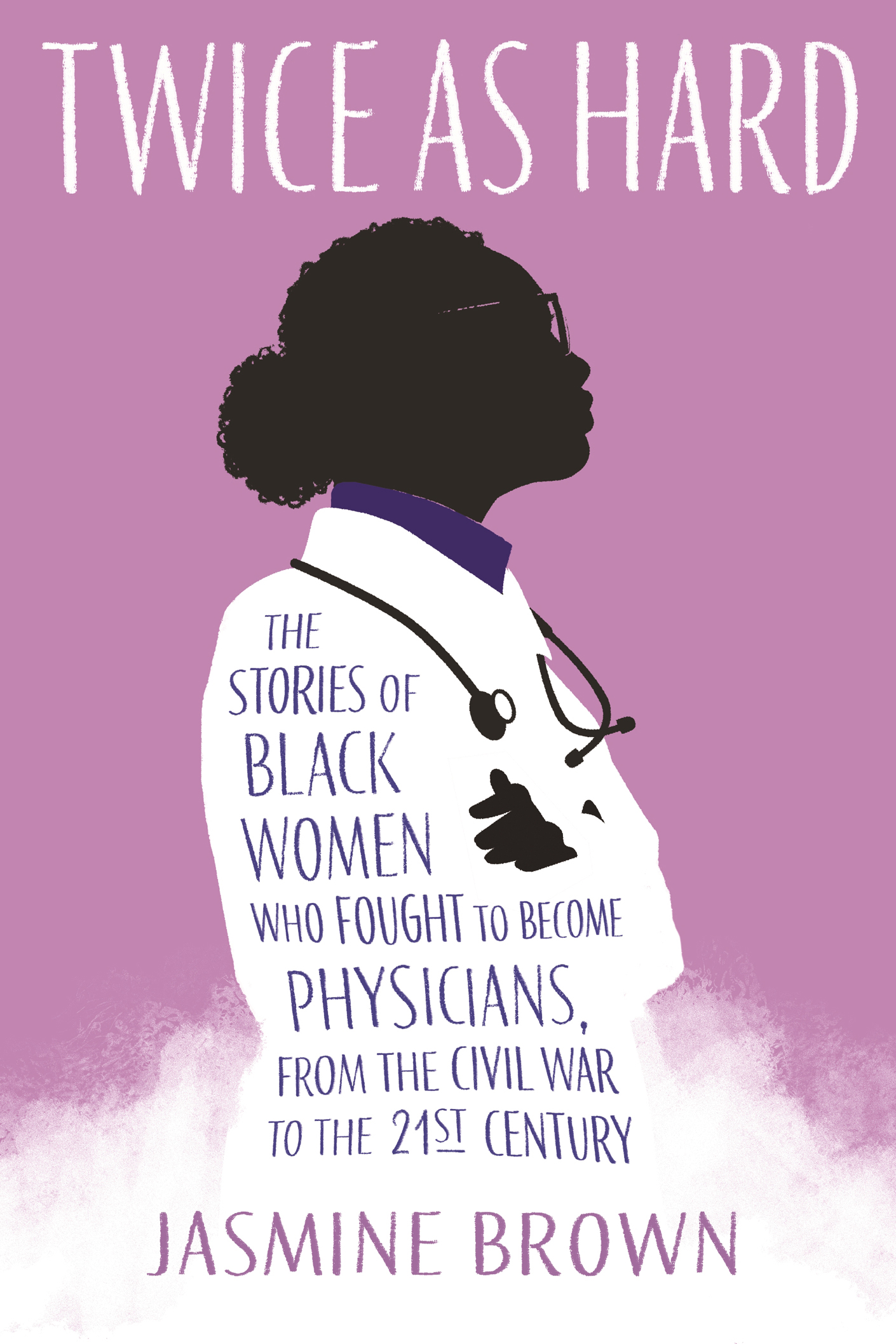

Jasmine Brown - Twice as Hard: The Stories of Black Women Who Fought to Become Physicians, from the Civil War to the Twenty-First Century

Here you can read online Jasmine Brown - Twice as Hard: The Stories of Black Women Who Fought to Become Physicians, from the Civil War to the Twenty-First Century full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2023, publisher: Beacon Press, genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Twice as Hard: The Stories of Black Women Who Fought to Become Physicians, from the Civil War to the Twenty-First Century

- Author:

- Publisher:Beacon Press

- Genre:

- Year:2023

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Twice as Hard: The Stories of Black Women Who Fought to Become Physicians, from the Civil War to the Twenty-First Century: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Twice as Hard: The Stories of Black Women Who Fought to Become Physicians, from the Civil War to the Twenty-First Century" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

No real account of black women physicians in the US exists, and what little mention is made of these women in existing histories is often insubstantial or altogether incorrect. In this work of extensive research, Jasmine Brown offers a rich new perspective, penning the long-erased stories of nine pioneering black women physicians beginning in 1860, when a black woman first entered medical school. Brown champions these black women physicians, including the stories of:

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, who graduated from medical school only fourteen months after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed and provided medical care for the newly freed slaves who had been neglected and exploited by the medical system.

Dr. Edith Irby Jones, the first African American to attend a previously white-only medical school in the Jim Crow South, where she was not allowed to eat lunch with her classmates or use the womens bathroom. Still, Dr. Irby Jones persisted and graduated from medical school, going on to directly inspire other black women to pursue medicine such as . . .

Dr. Joycelyn Elders, who, after meeting Dr. Irby Jones, changed her career ambitions from becoming a Dillards salesclerk to becoming a doctor. In 1993, President Bill Clinton appointed Dr. Elders as the US surgeon general, making her the first African American and second woman to hold this position.

Brown tells the stories of these doctors from the perspective of a black woman in medicine. Her journey as a medical student already has parallels to those of black women who entered medicine generations before her. What she uncovers about these womens struggles, their need to work twice as hard and be twice as good, and their ultimate success serves as instruction and inspiration for new generations considering a career in medicine or science.

Jasmine Brown: author's other books

Who wrote Twice as Hard: The Stories of Black Women Who Fought to Become Physicians, from the Civil War to the Twenty-First Century? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.