Lydia Moland - Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life

Here you can read online Lydia Moland - Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

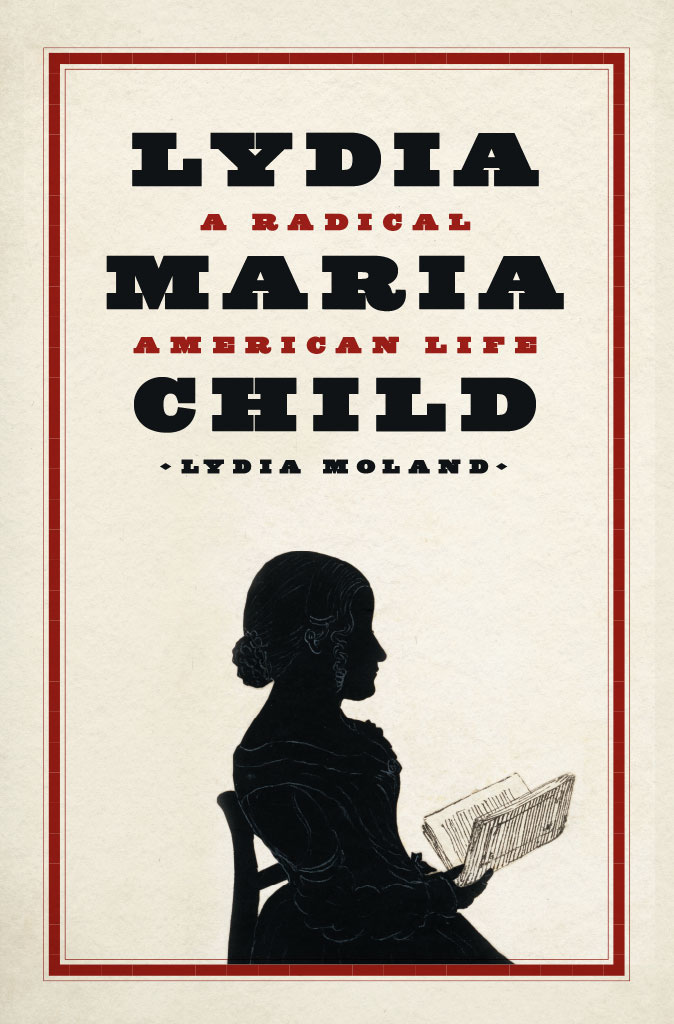

- Book:Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Child

A Radical American Life

Lydia Moland

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2022 by Lydia Moland

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71571-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71585-8 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226715858.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moland, Lydia L., author.

Title: Lydia Maria Child : a radical American life / Lydia Moland.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022007565 | ISBN 9780226715711 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226715858 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Child, Lydia Maria, 18021880. | Women abolitionistsUnited StatesBiography. | Women social reformersUnited StatesBiography. | Women authors, AmericanBiography. | Authors, American19th centuryBiography. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC HQ1413.C45 M65 2022 | DDC 326/.8092 [B]dc23/eng/20220223

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022007565

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my father and mother,

Ken and Barbara Moland:

loving parents of fierce daughters

and compassionate sons

This is a story of never living your life the same way again.

I have always loved asking the big questions. What is justice? What is truth? What about beauty? How should we live? By some miracle, I have managed to turn this love into a career by becoming a philosophy professor. I have devoted happy years of my life to parsing claims made by scowling nineteenth-century German philosophers and analyzing confounding arguments with the help of smart students. I have found in philosophy guidance on how to be moral, clarity about political principles, and an exhilarating argument for the necessity of art.

But after the presidential election of 2016, I decided something had to change. I decided it was time to come home: to find resources to confront my countrys new reality in our own history. On Inauguration Day 2017, I made my way to Washington, DC, in a van full of Colby College students, all of us ready to march in our nations capital. As we left Maine behind us, I had another thought. It was time, I decided, to turn to women.

This was going to be a problem. In nineteenth-century philosophy, women would be scarce. But two months later, spring break found me at the Schlesinger Library for the History of Women in America at Harvards Radcliffe Institute. I arrived with the criminally vague idea of researching the philosophical foundations of American abolitionism. I knew women had been powerful voices against slavery, but I didnt know who or how. But attacking an entrenched institutional evil, I imagined, must have entailed thinking philosophically. It must have required a clear articulation of concepts like justice, dignity, and humanity as well as a capacity to make arguments that changed peoples lives. An obliging librarian produced a box of archived letters. Among correspondence by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Louisa May Alcott, and Julia Ward Howe, one letter stood out.

The letter was clearly written by one activist to another. It was affectionate, firm, and principled. It balanced self-deprecating humor with gentle reproach. It deftly applied wisdom gained from a life of antislavery activism to the newer cause of womens suffrage. Its perfectly formed sentences testified to a clarity I craved. The handwriting was gorgeous. It was signed L. Maria Child. I had no idea who that was. Reader, I googled her.

What I found stunned me. Lydia Maria Child had written the first book-length argument against slavery in 1833a book so progressive in the cause of abolition and so scathing in its attack on Northern racism that Boston society ostracized her. She had been the first female editor of a major American weekly political journal. She had written a two-volume history of women and a three-volume history of religion. When she realized that her country needed guides to home economics, parenting, nursing, or aging, she wrote those too. She had tangled publicly with politicians and used her body to shield abolitionist speakers from violent mobs. When her marriage threatened to break her spirit, she risked scandal by living apart from her husband, managing nevertheless to forge a love story that ended only when he died in her arms. She even wrote Over the River and through the Wood. How had I never heard of this woman?

Among all these accomplishments, one thing fascinated me most. That was the story of how Child, once incontrovertible evidence of slaverys evil awakened her conscience, had never lived her life the same way again. Living by her conscience made her a radical, unwilling to accept the conventional wisdom of her time and unable to abide by its norms. She had aborted a fledgling career as one of Americas first female novelists. She had consigned herself to a life of poverty. She had lost friends and alienated family. Decades later, after a civil war had accomplished what abolitionist activism alone could not, she was still fighting. How had she done that? What had prepared her for that moment of conversion, and what had sustained the life of activism that followed? And what could the example of her life teach me about how to live my own?

* * *

Pursuing these questions took me on a multilayered journey. It took me physically to the grave of an eighteenth-century Catholic priest near Norridgewock, Maine. It brought me to the hallowed halls of the Boston Athenum, a library that, for disputed reasons, had terminated Childs membership in the wake of her ostracism. It led me to the wood-paneled rare books room at the New York Public Library, where evidence of Childs paralyzing despairbrought about by professional failure and personal heartbreakfilled my eyes with tears. And it brought me to Wayland, Massachusetts, where Child lived the last decades of her life and where she died. There, at a Sunday service at Waylands First Parish Church, I heard a choir sing her words, set to music by a local composer. When they finished, a parishioner lit a candle. The minister invited the spirit of Lydia Maria Child to join us, and I felt a chill run down my spine.

More metaphorically, my questions about Childs lifetime of activism took me on a journey through bad arguments in my countrys history. I learned about the reasoning that granted Maine statehood in exchange for slaverys expansion in Missouri. I confronted the rationale within the abolitionist movement for forbidding women to speak. I worked through the arguments that average Bostonians used to keep from caring about slavery and the justifications that allowed Northerners to abandon newly emancipated Black men and women to their fate during Reconstruction. The arguments were bad, but they felt very familiar. They sound a lot like arguments we hear on other topics every day.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life»

Look at similar books to Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.