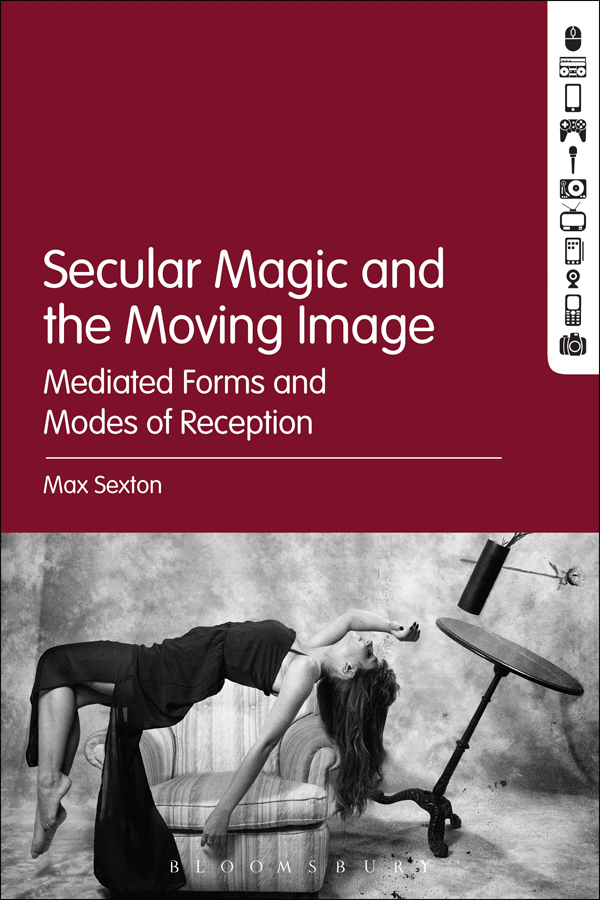

This book explores the idea of secular magic Rational technological marvels, including film, and a fascination for enchantment and wonder have, since the advent of the magic lantern, transmuted older beliefs in the supernatural into secular attractions. Boundaries of belief and doubt, magic and science are some of the topics that are discussed in this volume as also the cultural sensibilities through which sense is made of secular conjuring magic in its many variegated forms primarily on television, as well as film.

Initially, the book is concerned with the formal and aesthetic changes that television has undergone since its growth in popularity in the 1950s and its impact on a particular form of entertainment that emerged from the theatrical variety act the presentation of secular magic. Realism has also been a mode that has, throughout television history, dominated much of its output and continues to be tied to arguments about its essential nature as it transmits images and sound instantaneously. Yet its liveness, if a dominant paradigm, ignores how conjuring magic has sought to destabilize realism and the boundaries between belief and doubt and the ordinary and the extraordinary. At the same time, the enduring fascination for magic on television including recent popular acts by, for example, David Blaine reveals much about how relations between everyday life and the extraordinary are played out. The imbrication of magic, especially in the presentation of street magic, with the daily lives of its participants not only destabilizes reality but offers a utopian sensibility. Such magical transformations of the mundane complicate our understanding of television as a medium whose main aesthetic is realism, as well as other debates about the uncanniness of television as it brings the world into our living rooms.

The performance of magic transcends cultural and linguistic barriers because of the relatively few competencies that are required for the majority of conjuring tricks. Although it has built a globalized culture of illusion and sleight of hand, it appears to lack deeper structures of meaning. However, if apparently trivial, magics diverse content has sustained a remarkable longevity and enjoyed enduring popular appeal. Moreover, if definitions of secular magic on the moving image are difficult due to its ability to be so varied, it raises possibilities that the cultural construction of magic is bound to the social application of broadcasting and recording technology.

The art of illusion with its secular development has led to modes of entertainment and realism that increasingly cannot be understood either in aesthetic terms or in narrative and contextual terms that articulate complex ideas to do with both image making as well as the relationship between forms of moving image. Such relationships continue to complicate any single definition of screen media within the mediatization of the live and converging mediums of television and film at the beginning of the twenty-first century. How a number of programmes by Penn and Teller, David Blaine, Criss Angel and others function to explore ideas about truth and deception is shown to depend on the cultural as well as visual possibilities of illusion.

Since the invention of the moving image in the 1890s, secular magic and the moving image have had a history of affinity. Hitherto, the relationship between them has been usually understood in terms of the magic of the movies and suggests the power of moving images to conjure marvellous worlds and evoke feelings of amazement. But this book is not about the history of special effects in the movies or a history of magic. Rather, it is an attempt to determine the influence and status of secular magic within its various complex modes of delivery in contemporary television and, eventually, in film.

The overlap and tension between these modes reveal the often complex way that secular magic can be understood in contemporary screen media. The book contends that the phenomenon of secular magic creates distinct cultural forms that have been responsible for the commercial production of modes whose appearance in recent television and cinema has been overlooked. The act of magic permits a relationship between the producer and the spectator to resemble that between conjuror and audience; the quality of the magical performance is judged by its ability to deceive and mystify as well as, at other times, inform and empower.

The emergence of the modern stage magician in the nineteenth century inaugurated a century of close links between the performance of magic as education, entertainment and screen projection. This would climax when film coincided with the golden age of theatrical magic at the beginning of the twentieth century. However, unlike the formative years of film, the need for ever greater novelties in the 1990s and the twenty-first century has been less about the magical effect as an innovation, and more about how different modes within the moving image have interreacted to provide the maximum cultural value to audiences and producers.

Such an interest in its cultural construction raises questions about its practices and the real world, or relations between the moving image and society. Specifically, it is the relationship between the live performance of magic and the image that dominates many of the debates in this book. The motion picture industry is older than the electronic (television) image and exists as a long-established art. Despite resistance from many quarters, many of the techniques and qualities of film were eventually adopted by television drama which was shot on film for the production of the telefilm. Neverthless, the production of certain types of programmes recorded in the television studio, such as the variety show, remained live, and in a magic show, the experience of the audience continues to be a sense of immediacy of events happening as they appear on the screen.

If the sense of immediacy made little difference to dramatic programmes that relied on the camera direction and editing techniques of film, other types of entertainment, including the live performance of magic on television, depended on the continuing understanding that the audience had a direct access to the reality that was being transmitted. Yet, as John and practices within television, as well as film. The representation of magic touches on matters ontological, but in order to do so, it is important to realize that an understanding of the text depends on how it participates in broader systems of cultural meaning.

A desire to identify secular magic as possessing the traits and characteristics of a cohesive system is not an argument that magic can ever have the nature of a genre such as, say, science fiction with its semantic and syntactic conventions. Rather, if magic appears at moments to become a formulaic discourse, then the marks of coherence loosen due to its inclusion of discourses to do with the randomness and uncertainty associated with the real world. The positioning of the spectator between certainty and scepticism allows a dynamic interplay between the various narratives cabinets, ropes, spirits, swords, coins and flower bouquets involves attractions and represents its structural properties, but so too are evolving modes that present contradictory truths as bodies and minds are apparently freed from the ordinary physical constraints of the physical world.