PREFACE

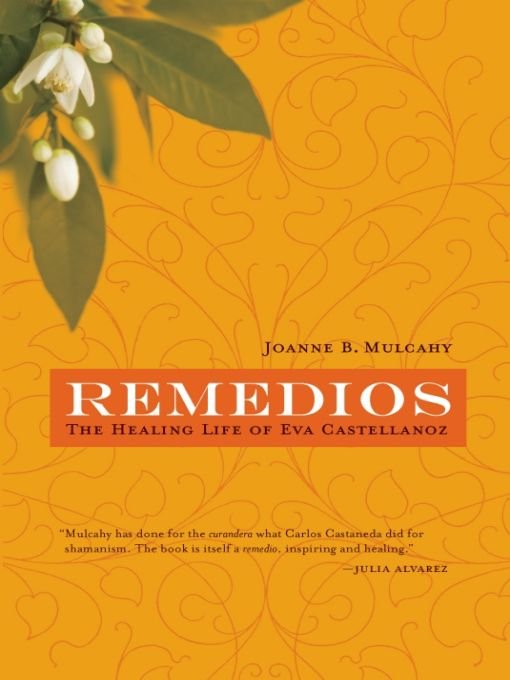

To be a curandera, says Eva Castellanoz, is to have faith. Curanderismo from curar (to heal)passed to Eva from her mother, Mara Concepcin Jurez Silva, and to both of them from God. Healing is a gift, the curandera, its vessel. The potential lies within, but a person must choose to develop it. Healers in many cultures are sharp-eyed visionaries at the margins; they see what others cannot. When Eva was very young, she would go each morning to the fields in the Rio Grande Valley with her father, Jos Loreto Fidel Silva. Gathering dew from the leaves of the squash, beans, and corn, he would anoint Evas face. He always wiped my eyes with the dew, she recalls. He would say to me, You will see things differently.

Eva wants us to see differently, too, through the metaphors she crafts in everyday life, in teaching, and in healing. Perhaps she absorbed the importance of metaphor from her parents indigenous world, for the Aztecs believed that art made things divine. The only real knowledge on earth could be glimpsed through in xchitl in cucatlthe Nahuatl phrase for poetry, translated as flor y canto or flower and song. Life for the Aztecs was wonderfilled but fleeting: Although it be jade, it will be broken/although it be gold, it will be crushed.

Even as a child, Eva grasped this contradiction; she wanted to be a poet. As an adult, she has mastered one of poetrys central tools. Evas metaphors evoke her own stubborn self as la mula ; the gang members she works with as golden treasures; Catholicism as a too-tight dress; spiritual legs as the body parts that truly support us; culture as a tree with deep roots, healthy bark and limbs; faith as something beyond our measuring tools.

To understand metaphor is to go beyond logic. When Eva says that she ties her lions back at night, we must accept that her rage at social injustice is an animal, that something can be itself and something else at the same time. We have to envision one aspect of life in terms of another. We must link separate worlds and turn the abstract into concrete aliveness. Only then can we move from blinkered vision to the wide-angle view, from illness to health, from despair to hope. Metaphor is our bridge, if we are willing to cross over it to reach new understanding. Evas goal is nothing less than social transformation, but she begins with the simplest of movements : pressing the dew onto our eyes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am deeply indebted to Eva Castellanoz, who gave me gifts beyond measure: faith and friendship. Her trust that I could shape a story of her life urged me forward. I dedicate this book to her remarkable spirit.

Thanks go to all the Castellanoz clan, especially Evas children and their spouses: Diego Fidel and Cecelia (Cece) Castellanoz, Rosario Isabel (Chayo) and Ricardo Garcia, Juan Rafael (Ralph) Castellanoz, Maria de Lourdes (Maria) and Rogelio Gallegos, Enrique (Ricky) and Yolanda Castellanoz, Martin (Marty) and Priscilla (Flaca) Castellanoz, Maria Cristina (Chana) and Luis (Brown) Ramirez, Sergio (Toe), whose spirit lives on through the love and invocations of his family, and Javier (Cami) Castellanoz. They welcomed me into their lives, fed me in numerous ways on visits to Nyssa and on my trip to Pharr, Texas, and waited patiently for the completion of this book.

The support of my family and friends is bedrock. My parents, Jeanne and Paul Mulcahy, nurtured the creative pursuits of all their children. My sister Pats support and editorial advice were essential. Many friends offered valuable commentary on parts of the book: Judith Barrington, Judy Blankenship, Ana Callan, Andrea Carlisle, Norma Cant, Guadalupe Guajardo, Ruth Gundle, Cindy Williams Gutirrez, Kirin Narayan, Karen Rodriguez, and Marilyn Sewell. Others buoyed my spirits with engaged conversation: Bob Amundson, Perrin Kerns, Elinor Langer, Scott Lyons, Bob McCarl, Paul Merchant, Holly Sylvester, and Sully Taylor. Special thanks go to the faculty and staff of the Northwest Writing Institute, especially director Kim Stafford and administrative assistant Diane McDevitt. Their generosity created a home for my work at Lewis and Clark College.

I am deeply indebted to the vision and encouragement of editor Barbara Ras. Managing editor Sarah Nawrocki, always patient as well as efficient, shepherded the manuscript with great care. Julie Van Pelts initial edits alerted me to critical questions. Copyeditor Katherine Silvers keen eye and appreciation for language made Remedios a far better book. Thanks to Jan Boles for his endless generosity with photos. Nancy Nusz, Gabriella Riccardi, Carol Spellman, and Amanda Andersen of the Oregon Folklife Program aided my research and shared my commitment to Evas story. Christine Marasigan, Jae Carey, Carol Cheney, and Laura Marcus helped transcribe taped interviews.

Institutional and financial support came from multiple sources. The Rene Bloch Foundation financed travel to Texas in 2001. The Espy Foundation and the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology granted residencies in 2006 and 2007, respectively. The staff at the Menucha Retreat Center unfailingly welcomed me. The Graduate School of Education and Counseling of Lewis and Clark College provided funds for research, tape transcription, technology assistance, and countless other forms of aid.

My deepest gratitude extends to my wise and patient husband Bob. He read and responded to the entire manuscript several times. His love and encouragement continue to sustain me.

A NOTE ON METHODS

This book blends creative nonfiction with ethnographythe portraits that anthropologists, folklorists, and other social scientists write. Ethnographic fieldwork relies on interviews and participant observationobserving, recording, and taking part in cultural life. Many creative nonfiction writers, particularly immersion journalists who spend extended periods with a person or group, use similar methods. Writers in both realms employ dialogue, scene, and other fictional techniques to engage readers. As a writer and a folklorist, I have tried to draw the most useful tools from each domain to convey Evas experience.

The quoted material and stories of Evas life come from interviews conducted in Portland and Nyssa, Oregon, between 1992 and 2008, and on a trip to Pharr, Texas, in 2001. I taped twenty-one interviews; at other times, I wrote notes on our extended conversations. I kept journals while doing fieldwork in Oregon and Texas and during visits to Evas birthplace of Valle de Santiago in 2005 and 2006. Both trips to Mexico revealed local historical materials unavailable in the United States. Those visits also gave me a feeling for Evas early years. Though Eva is bilingual and we taped interviews in English, I studied Spanish over a tenyear period. This enabled me to read primary documents in Spanish and deepen my understanding of her life. In the text, Spanish words that might be unfamiliar to readers are italicized. Accents appear in some names and not others according to the individuals spelling preferences.

The structure of the book is episodic rather than chronological; it is organized around our time together in different locations. My intention is to invite readers into Evas casita in Nyssa, to her childhood home in South Texas, and to the Owyhee Mountains in eastern Oregon. At times, I merged into one story material Eva told me in different interviews. For example, Eva repeatedly described how she died when she gave birth to her ninth child, Cami, and was called to healing (a story that appears in chapter 9). Most of the short segments that open each chapter as epigraphs reappear in the text; I repeat Evas words for emphasis and to show the context from which they emerged. I kept Evas speech as close to the taped material as possible, occasionally changing verb tenses and other elements of grammar for clarity. I hope these methods help animate Evas humor, lively use of language, and storytelling gifts.