Michael Kube-McDowell - Odyssey

Here you can read online Michael Kube-McDowell - Odyssey full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2004, publisher: I Books, genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Odyssey

- Author:

- Publisher:I Books

- Genre:

- Year:2004

- ISBN:0-743-47924-6

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Odyssey: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Odyssey" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Odyssey — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Odyssey" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

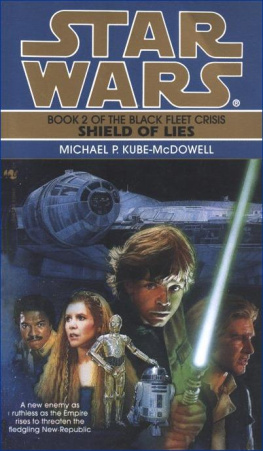

Michael P. Kube-McDowell

Odyssey

For all the students

who made my seven years of teaching time

well spent,

but especially for:

Wendy Armstrong, Todd Bontrager, Kathy Branum, Jay amp; Joel Carlin, Valerie Eash, Chris Franko, Judy Fuller, Chris amp; Bryant Hackett, Kean Hankins, Doug Johsnson, Greg LaRue, Julie Merrick, Kendall Miller, Matt Mow, Amy Myers, Khai amp; Vihn Pham, Melanie amp; Laura Schrock, Sally Sibert, Stephanie Smith, Tom Williams, Laura Joyce Yoder, Scott Yoder

And for

Joy Von Blon, who made sure they always had something good to read.

My Robots

by Isaac Asimov

I wrote my first robot story, Robbie, in May of 1939, when I was only nineteen years old.

What made it different from robot stories that had been written earlier was that I was determinednot to make my robots symbols. They were not to be symbols of humanitys over-weening arrogance. They werenot to be examples of human ambitions trespassing on the domain of the Almighty. They werenot to be a new Tower of Babel requiring punishment.

Nor were the robots to be symbols of minority groups. They werenot to be pathetic creatures that were unfairly persecuted so that I could make Aesopic statements about Jews, Blacks or any other mistreated members of society. Naturally, I was bitterly opposed to such mistreatment and I made that plain in numerous stories and essays-butnot in my robot stories.

In that case, whatdid I make my robots?-I made them engineering devices. I made them tools. I made them machines to serve human ends. And I made them objects with built-in safety features. In other words, I set it up so that a robotcould not kill his creator, and having outlawed that heavily overused plot, I was free to consider other, more rational consequences.

Since I began writing my robot stories in 1939, I did not mention computerization in their connection. The electronic computer had not yet been invented and I did not foresee it. I did foresee, however, that the brain had to be electronic in some fashion. However, electronic didnt seem futuristic enough. The positron-a subatomic particle exactly like the electron but of opposite electric charge-had been discovered only four years before I wrote my first robot story. It sounded very science fictional indeed, so I gave my robots positronic brains and imagined their thoughts to consist of flashing streams of positrons, coming into existence, then going out of existence almost immediately. These stories that I wrote were therefore called the positronic robot series, but there was no greater significance than what I have just described to the use of positrons rather than electrons.

At first, I did not bother actually systematizing, or putting into words, just what the safeguards were that I imagined to be built into my robots. From the very start, though, since I wasnt going to have it possible for a robot to kill its creator, I had to stress that robots could not harm human beings; that this was an ingrained part of the makeup of their positronic brains.

Thus, in the very first printed version of Robbie (it appeared in the September 1940Super Science Stories, under the title of Strange Playfellow), I had a character refer to a robot as follows: He just cant help being faithful and loving and kind. Hes a machine,made so.

After writing Robbie, which John Campbell, ofAstounding Science Fiction, rejected, I went on to other robot stories which Campbell accepted. On December 23, 1940, I came to him with an idea for a mind-reading robot (which later became Liar!) and John was dissatisfied with my explanations of why the robot behaved as it did. He wanted the safeguard specified precisely so that we could understand the robot. Together, then, we worked out what came to be known as the Three Laws of Robotics. The concept was mine, for it was obtained out of the stories I had already written, but the actual wording (if I remember correctly) was beaten out then and there by the two of us.

The Three Laws were logical and made sense. To begin with, there was the question of safety, which had been foremost in my mind when I began to write stories aboutmy robots. Whats more I was aware of the fact that even without actively attempting to do harm, one could quietly, by doing nothing, allow harm to come. What was in my mind was Arthur Hugh Cloughs cynical The Latest Decalog, in which the Ten Commandments are rewritten in deeply satirical Machiavellian fashion. The one item most frequently quoted is: Thou shalt not kill, but needst not strive/Officiously to keep alive.

For that reason I insisted that the First Law (safety) had to be in two parts and it came out this way:

1. A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

Having got that out of the way, we had to pass on to the second law (service). Naturally, in giving the robot the built-in necessity to follow orders, you couldnt forfeit the overall concern of safety. The second law had to read as follows, then:

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

And finally, we had to have a third law (prudence). A robot was bound to be an expensive machine and it must not needlessly be damaged or destroyed. Naturally, this must not be used as a way of compromising either safety or service. The Third Law, therefore, had to read as follows:

3. A robot must protect its own existence, as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Of course, these laws are expressed in words, which is an imperfection. In the positronic brain, they are competing positronic potentials that are best expressed in terms of advanced mathematics (which is well beyond my ken, I assure you). However, even so, there are clear ambiguities. What constitutes harm to a human being? Must a robot obey orders given it by a child, by a madman, by a malevolent human being? Must a robot give up its own expensive and useful existence to prevent a trivial harm to an unimportant human being? What is trivial and what is unimportant?

These ambiguities are not shortcomings as far as a writer is concerned. If the Three Laws were perfect and unambiguous there would be no room for stories. It is in the nooks and crannies of the ambiguities that all ones plots can lodge, and which provide a foundation, if youll excuse the pun, forRobot City.

I did not specifically state the Three Laws in words in Liar! which appeared in the May 1941Astounding. I did do so, however, in my next robot story, Runaround, which appeared in the March 1942Astounding. In that issue on line seven of page one hundred, I have a character say, Now, look, lets start with the three fundamental Rules of Robotics, and I then quote them. That, incidentally, as far as I or anyone else has been able to tell, represents the first appearance in print of the word robotics-which, apparently, I invented.

Since then, I have never had occasion, over a period of over forty years during which I wrote many stories and novels dealing with robots, to be forced to modify the Three Laws. However, as time passed, and as my robots advanced in complexity and versatility, I did feel that they would have to reach for something still higher. Thus, inRobots and Empire, a novel published by Doubleday in 1985, I talked about the possibility that a sufficiently advanced robot might feel it necessary to consider the prevention of harm to humanity generally as taking precedence over the prevention of harm to an individual. This I called the Zeroth Law of Robotics, but Im still working on that.

My invention of the Three Laws of Robotics is probably my most important contribution to science fiction. They are widely quoted outside the field, and no history of robotics could possibly be complete without mention of the Three Laws. In 1985, John Wiley and Sons published a huge tome,

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Odyssey»

Look at similar books to Odyssey. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Odyssey and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.