Destroyer 79: Shooting Schedule

By Warren Murphy and Richard Sapir

Prologue

Nemuro Nishitsu knew that the emperor would one day die.

Many Japanese refused to think about it. Almost no one believed in Emperor Hirohito's immortality anymore. That he was immortal was no more logical than the belief that the emperor's father had been immortal or his grandfather before him and on back to the fabled Jimmo Tennu, the first of his line to sit on the Chrysanthemum Throne. And the first Japanese emperor to die.

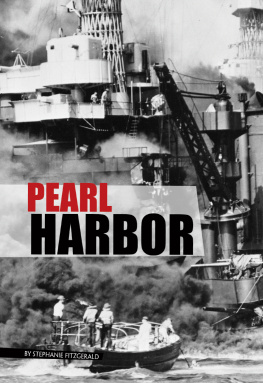

That the emperor was divine was without question. Nemuro Nishitsu believed it on the day he left for Burma on a troop transport in 1942. He believed it all through the monsoon rains that beat on his helmet and his resolve through the endless days fighting the British and Americans.

He believed it in 1944, when Merrill's Marauders captured General Tanaka's Eighteenth Army. Then-Sergeant Nemuro Nishitsu managed to escape. He took his faith in his emperor into the jungles, where he would fight on, even if he was the last Japanese to hold out. He would never surrender.

Nemuro Nishitsu learned to eat from the monkeys. What they ate, he knew was safe. What they avoided, he assumed was poison. He learned to subsist on bamboo shoots and stolen yams, and to use the jungle maggots to clean out the pus from the ulcers that infected his legs. Sometimes he would eat the maggots after they had done their duty to the emperor.

He killed anyone wearing an unfriendly uniform. Months passed and the uniforms became fewer and fewer. But Nemuro Nishitsu fought on.

They found him in a ditch during monsoon season.

The water cascading around his body was an unhealthy diarrhea yellow. Nishitsu had malaria.

British soldiers took him to an interment camp, where he recovered well enough to enter the general POW population.

It was in this camp that Nemuro Nishitsu first heard the whispers among his unit-the traitorous suggestion that Japan had surrendered to the Americans after some mighty military blow.

Nemuro Nishitsu had scoffed at such a thing. No blow could bring the emperor to surrender. It was not possible. The emperor was divine.

Then they were told they were going home. Not as the victors, but as the vanquished.

Japan was no longer Japan, Nemuro Nishitsu discovered, to his horror. The emperor had renounced his birthright. Japan had surrendered. It was unthinkable. Americans ran the country under the mandate of an American Constitution that prohibited the mere existence of a Japanese army. Tokyo was a sea of rubble. And his home town, Nagasaki, was a desolation of shame.

What astonished Nemuro Nishitsu more than anything else was the meekness of his formerly proud countrymen.

He discovered this the day in late 1950, the twenty-fifth year of the emperor's reign, when a drunken SCAP bureaucrat nearly ran him over while Nishitsu was crossing the ruined Ginza to the little stall where he sold sandals in order to eat.

Nishitsu was not hurt. A Japanese policeman came upon the accident scene, and instead of berating the obviously drunken American, asked him if he wanted to press charges against Nishitsu. Or would he settle for restitution?

The drunken American settled for Nishitsu's sandal stock and every yen on his person.

On that day, Nemuro Nishitsu tasted the bitterness Japan had spread throughout Asia, and it galled him. "Where is your rage?" he would ask his friends. "They have humbled us."

"That is the past," his friends would say in furtive whispers. "We have no time for that. We must rebuild."

"And after you have rebuilt, will you find your anger then?"

"After we rebuild, we must build upon our accomplishments. We must catch up to the Americans. They are better than us."

"They have conquered us," Nishitsu had retorted hotly. "That doesn't make them superior, only fortunate."

"You were not here when the bombs fell. You do not understand. "

"I understand that I fought for my nation and my emperor and I have returned to find my people have lost their manhood," he spat contemptuously.

Nemuro Nishitsu was disgusted by all he saw. Shame blanketed Japan like the smog that came as the industries were rebuilt and revitalized. When he awoke in the morning, he could smell it-in the air. It etched the faces of the young men, and the fine women. No Japanese could escape it. Yet they all tried. And their faith was not Bushido, not Shinto, but American. Everyone wanted to be like the Americans, who were so mighty that they had humbled the once-invincible Japanese.

Nemuro Nishitsu knew that he never wanted to be like the Americans. He also understood that the destiny of Japan lay not in the past, but in the future. He joined his countrymen in building that future until even he gradually lost his bitterness and hatred in the great rebuilding frenzy.

It took years. The great Zaitbatsu companies had been dismembered by the Occupation government. Work was hard to come by. But opportunities awaited the bold. Slowly Nishitsu started a radio business to fill the manufacturing void. It grew, thanks to American transistors. It prospered, thanks to American markets. It diversified, thanks to American microchips-until Nemuro Nishitsu's bitterness faded as he was hailed as one of the rebuilders of Japan's postwar economy, friend of the emperor, and winner of Japan's highest honor, the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure. He became an oyaji, an "old man with power." And he was content.

The bitterness all came back when the emperor died.

Nemuro Nishitsu was in his Tokyo office, with its view of the Akihabara area, the electronics district he had helped turn into one of the most expensive stretches of real estate in the world, when his secretary came in and bowed twice before informing him of the emperor's death. He was surprised to see the tears in her eyes, for she was of the younger generation who never knew a time when the emperor was universally believed divine.

Nemuro Nishitsu took the news in silence. He waited until the secretary had left the room before succumbing to weeping.

He wept until he had no tears left.

The invitation to attend the funeral was not unexpected. He turned it down. He preferred, instead, to watch the funeral procession from the street, with the multitudes. As the one-ton cedar coffin rolled by, carried by black-gowned pallbearers, he let the rain fall on his face. And in his heart, he felt that it had wiped away the years since he had gone off to war in his emperor's name.

It was not too late to redeem his faith, Nemuro Nishitsu decided as tears of release mixed with the softly falling rain.

He spent the next week going through the employment records of the Nishitsu Group. He spoke with his office managers and vice-presidents in quiet, forceful tones. Those who gave the correct answers to his artfully crafted questions were asked to find others who thought as they did.

Months went by. The wisteria blooms of spring gave way to the heat of the summer. By fall, he had culled the most trustworthy employees of the Nishitsu group, from the highest officers to the lowliest salarymen.

They were called to a meeting. Some came from the halls of the Nishitsu Group world headquarters in Tokyo, on the island of Honshu. Others came from Shikoku or Kyushu. Some came from abroad, even as far away as America, where they managed Nishitsu car factories. They had many names, as many faces, and skills in plenty, for the Nishitsu Group was the largest conglomerate in the world, and it hired only the best.

The chosen ones sat on the floor in their identical white shirts and black ties. Their faces were impassive as Nemuro Nishitsu stepped up to the bare floor at the head of the room. The room was the conference assembly hall of the Nishitsu Group, where every morning the workers joined in morning calisthenics.

Next page