Curious Notions

Crosstime TrafficBook Two

Harry Turtledove

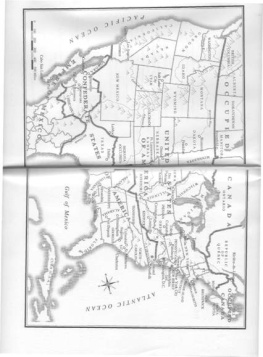

Every now and then, Lucy Woo could pretend San Francisco was a great city in a great country. Sometimes, when she hurried south toward Market Street, the fog would be just starting to lift. Through the thick, wet, salty mist, the big buildings on Market would look as fine as if they were new and in good repair. They loomed up like dinosaurs, grand and imposing.

And dead. When the sun came out, it pricked pretense. It showed the long-unpainted bricks, the peeling plaster, the broken windows. Some of the buildings still had cracks from the quake of 1989, and that was more than a hundred years ago now. Here and there, vacant lots and piles of rubble showed where buildings had been pulled down or fallen on their own. Lucy stayed as far from the rubble as she could. Squatters built shacks and caves from it. Some of them were harmless. Some weren't.

Traffic was a swarm of people on foot and on bicycles. You made your own path and you pushed ahead. If you didn't, you'd never get anywhere. Trucks and rich people's cars crawled along. They couldn't go anywhere in a hurry, either. Even ambulances got stuck. People died on the way to the hospital because they couldn't get there soon enough.

Only one kind of car horn made everybody jam onto the sidewalk and get out of the way. That particular shrill scream was reserved for German cars alone. If Americans didn't clear a path in a hurry, the Kaiser's men were liable to start shooting. They didn't always, or even very often, but you never could tell.

This morning, Lucy had to move aside for the occupiers three times in the space of four blocks. She was furious. She was also frightened. If she was late to her job at the shoe factory, they might let her go. That would be awful. Her family really needed the money she brought in, even if it was only eight dollars a week.

A Mercedes rolled by. Bigwigs in high-crowned caps and fancy uniforms sat inside. Bodyguards in steel helmets with ornamental spikes rode shotgun. That was what people called it, anyhow. But they didn't carry shotguns. Assault rifles were a lot more deadly.

The big blond man who scowled down at Lucy wasn't mad at her. "I hate those so-and-sos," he said. "They think they own the world. Well, they do, near enough, but they don't have to act like it."

"Yes," Lucy said, and let it go at that. Her own features were almost as Chinese as her name. One of her great-grandmothers had been Irish. That made her nose and chin a little sharper than they might have been otherwise.

Even saying yes to the man was taking a chance. He might have belonged to the Feldgendarmerie, the Kaiser's secret police. And if he didn't, he was taking a chance talking to her. A sixteen-year-old Chinese girl wasn't a likely snoop. The Germans looked down their noses at what they called Orientals. Again, though, you never could tell.

Horn still screeching, the Mercedes plowed forward. The blond man looked daggers after it. As people unsquashed and started moving, he said, "I'm late. It's their fault. It's not mine. You think my boss will care?"

"Not if he's like mine," Lucy said. "I've got to hurry, too." She dived into the crowd. Being short had few advantages. Disappearing easily was one of them.

He didn't follow her. She made sure of that. And he couldn't know who she was. San Francisco was full of Chinese faces. She hurried on to the shoe factory. If she stepped on a few toes, well, some other people stepped on hers, too. And if she stuck an elbow in the side of a fat woman who blocked her way, she wasn't about to let that fat woman make her late. She wouldn't let anybody make her late.

She punched in just barely on time. Punching in wasn't good enough. She had to get to her machine on time, too. The foreman was a bald man named Hank Simmons. He was so mean and strict, he might have thought he was a German. But Lucy didn't quitegive him an excuse to yell at her. A couple of women who came in right after her weren't so lucky. They got scorched.

Lucy's job was to sew instep straps onto women's shoes. That was what she did, ten hours a day, six days a week. Other women in the big building had other jobs. Some nailed on heels. Some stitched soles to uppers. Some sewed on decorative trim. They all did the same thing through the whole shift, over and over and over again.

Some of them were younger than Lucy. A few couldn't have been more than eleven or twelve. Some were gray-haired grandmothers. Some were Chinese, some white, some Japanese, some Mexican, some black. San Francisco held a few of just about every kind of people under the sun. And the Kaiser's officials treated them all just the same way: lousy.

When Lucy's foot hit the button, the sewing machine snarled to life. She guided the strap and the upper through the machine. The vibration made her hands tingle. She shook them a couple of times. She always did, first thing in the morning. After that, she forgot about it.

Other sewing machines buzzed, too. Nail guns clacked. Off in the back, electric leather cutters made what was almost a chewing noise. Lucy wouldn't have wanted that job for anything. They had their own foreman back there, and he screamed at you if you wasted even a scrap of leather.

"How's it going?" asked the sandy-haired woman on the machine next to Lucy's. She was twice Lucy's age. She'd been making shoes in here since she was fourteen. She'd go right on doing it till she couldn't any more.

"I'm okay, Mildred. How are you?" Like Mildred and most of the others in the factory, Lucy could work without looking at what she was doing. Her hands did it whether she watched or not. She was sure she could sew straps in her sleep.

Everybody said the same thing. Every so often, though, someone would stop paying even the little bit of attention she needed to do the job. The shriek of pain that followed would make everyone jump. After that, people would be careful... for a little while.

Mildred's thin face was always sour. She looked even more unhappy now. "My boy is sick with something," she said. "Haven't got the money for a doctor. Haven't got the time, neither." Grimly, she went on sewing.

Lucy tossed a finished upper into the bin by her station. She started to sew another one at the same time as she asked, "Who's watching him, then?" It wouldn't be Mildred's husband. He was a longshoreman, and worked even more hours than she did.

"My kid sister," Mildred answered. "She just had her own baby, you know, and she can't go back to work yet."

"Sure," Lucy said. Mildred and her family were better off than some, even if she didn't realize it. At least she and her husband were working. And her kid sister was able to stay home for a while after she had a baby. Not that staying home with a brand-new one was any vacationLucy had helped her own mother with her brother, though she'd been little then. But plenty of women in the USA couldn't afford to stay home at all. As soon as they could stagger out of bed, back to work they went.

"It's not fair," Mildred whined. "It shouldn't ought to be like this."

Lucy only shrugged. "Tell it to the Germans," she said, which meant, You can't do anything about it, so forget it. Life was the way it was. She couldn't do anything about it herself. Mildred couldn't do anything about it. Nobody could do anything about it. You got by as best you could. What other choice did you have?

Whenever her bin filled up, a boy carried it off and brought her an empty. A quality inspector came by in the middle of the morning. He spoke to a couple of women, but left Lucy alone. If he spoke to you too often, you found yourself on the street. He hadn't bothered Lucy for weeks. She knew what she had to do, and she did it. She didn't do any more than she had to, not one single thing. It wasn't as if she were in love with her job. They paid her as little as they could get away with, and she worked as little as she could get away with. That was how things went, too.

![Harry Turtledove - Worlds that werent : [novellas of alternate history]](/uploads/posts/book/79050/thumbs/harry-turtledove-worlds-that-weren-t-novellas.jpg)