Hilda Doolittle - Helen in Egypt: Poetry

Here you can read online Hilda Doolittle - Helen in Egypt: Poetry full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1961, publisher: New Directions Publishing, genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Helen in Egypt: Poetry

- Author:

- Publisher:New Directions Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:1961

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Helen in Egypt: Poetry: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Helen in Egypt: Poetry" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Helen in Egypt: Poetry — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Helen in Egypt: Poetry" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

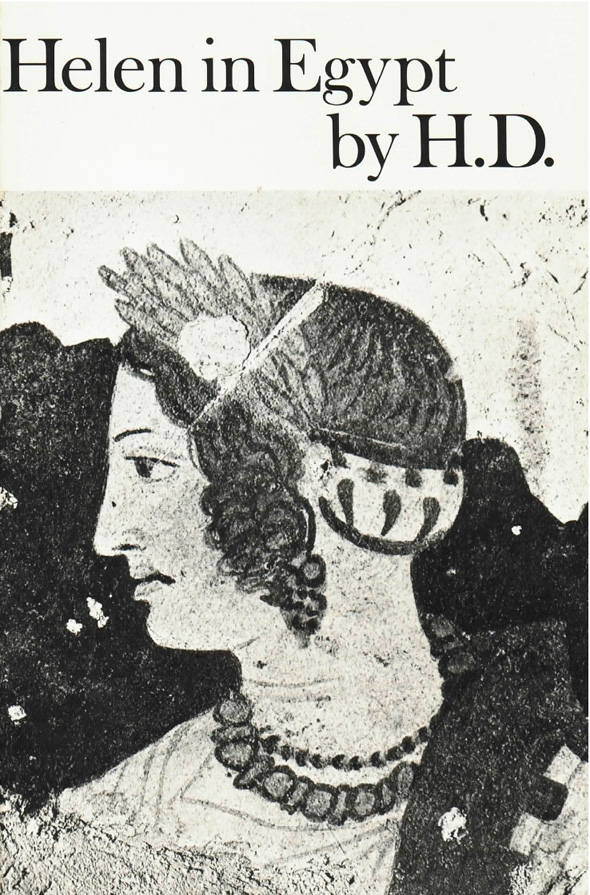

He was the inventor of the choral heroic hymn, and in that form raised lyric verse to the stature of the epic. He probably inspired Euripides to write his Helen in which, as the first scene shows us, Helen is in Egypt. All this is, of course, post-Homeric, yet post-Homeric versions of a myth often owe their inspiration to earlier, to half-forgotten, pre-Homeric sources. The only survival of Stesichorus twenty-six books of poems is a fragment of fifty lines. H.D.s Helen in Egypt is no translation, but a re-creation in her own terms of the Helen-Achilles myth. (As any historian knows, ancient dates shift according to theories in the measurement of time.) In a like scale of measurement, the Homeric epics came three hundred years later. (As any historian knows, ancient dates shift according to theories in the measurement of time.) In a like scale of measurement, the Homeric epics came three hundred years later.

By 900 B.C. the fall of Troy, as well as the complex of tragedy, both Greek and Trojan, surrounding it due to Greek genius had become timeless. In the fall of Troy was its beginning. It possessed the imagination of the poets. Troys end became the center of a galaxy of myths, a cycle in which the present tense is in a continual process of becoming (which is the language of poetry), in which the past becomes the future. It is appropriate that the overlying theme of H.D.s Helen in Egypt is one of rebirth and resurrection.

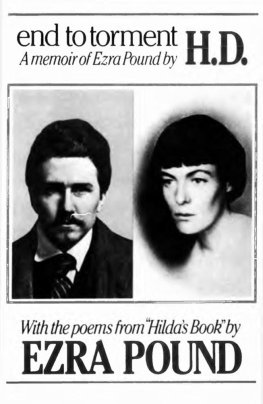

In her re-creation of the Helen-Achilles myth, it is no less appropriate that H.D. has chosen to wear the mask of Stesichorus. Her poem is written in a series of three-line choral stanzas; it is a semidramatic lyric narrative; each change of scene, each change of voice is introduced by a brief interlude in prose. Far from distracting the eye and ear of the reader, the design of the poem sustains the flow of its variations, and preserves its narrative unity. This innovation in the writing of Helen in Egypt is characteristic of H.D.s art, for from the day that Ezra Pound presented her early poems as examples of Imagiste verse she has been known as one of the principle innovators in American poetry. Although she has frequently acknowledged that the years of her early training in the writing of poetry owe their debts to Pounds remarks in his A Few Donts for Imagistes, her lyric gifts soon transcended the limitations of a school of writing.

Since 1931, the publication date of her book of poems, Red Roses for Bronze, it has been a misnomer to define her poems as Imagiste verse. However, she said, I dont know that labels matter very much. One writes the kind of poetry one likes. Other people put labels on it. Imagism was something that was important for poets learning their craft early in this century. But after learning his craft, the poet will find his true direction.

Without denying the brilliance of Pounds remarks in A Few Donts for Imagistes, it is true that the poets of that early group (all were young and high spirited) who later achieved distinction did so because of the individual merits of their poetry. Only those who pay more attention to labels than to poetry itself are likely to become confused by talk of movements and poetic manifestoes. It is clear that the memorable poets (including H.D. and Pound himself) among the Imagistes were not confused. These were the innovators of poetic form, and not those who wrote for the sake of merely seeming new or experimental. H.D.s concern has been centered upon the nature of reality, or as she has said less abstractly, more modestly, a wish to make real to myself what is most real.

Her innovations are allied to that concern, to evoke the timeless moment in a brief lyrical movement and imagery of verse. In the creation of her style no living poet has exerted a greater discipline in the economy of words. This is one of the reasons why H.D. is so often regarded as a poets poet, the creator of a classic style in modern verse. Her adaptation of Euripides Ion is less known than her shorter lyrics, nor are her longer poems in The Walls Do Not Fall, Tribute to the Angels, and The Flowering of the Rod, written in London during World War II, as well known as they should be. In retrospect these have become the forerunners of Helen in Egypt, the preparation for writing a new kind of lyric narrative, one in which the arguments in prose act as a release from the scenes of highly emotional temper in the lyrical passages.

The scenes of Helen in Egypt may be accepted as visions perceived after the event of the Trojan War. The war years of the Greek and Trojan ancients were no less vivid, less total in their results than our half-century of wars today. Without mentioning parallels between them, the situations in Helen in Egypt contain timeless references to our own times. It is as though the poem were infused with the action and memory of an ancient past that exist within the mutations of the present tense. It is H.D.s achievement to make us feel their presence. The dramatic scenes in the poem are written in defense of hated Helen and the conflicts of Helens guilt are the springs of tension throughout the poem.

The scenes are also a showing forth, an epiphany of the cycle of myths surrounding the active images of Achilles and Helen, visions in memory of her relationship to Thetis, strange scenes between Helen and Achilles, as well as those which show her meetings with Theseus and Paris but I shall not attempt to paraphrase the poem. As every intelligent reader of poetry knows, to paraphrase a poem is an impossibility, nor is it possible to reiterate in prose the actual meanings contained within the poem. During the past thirty years there have been many attempts to give T.S.Eliots. The Waste Land various meanings. These succeeded only in bewildering the author and he was left the choices of being amused, or flattered, or annoyed. It is best to say that Helen in Egypt increases its spell at each rereading.

A line of the poem reads, the old enchantment holds and that is true. Through the intonations of its choral music, the poem is an enchantment: there is magic in it. The twentieth century is not without its singular recreations of Greek myths. Of these Joyces Ulysses is best known. No less singular is Andr Gides essay in monologue, his Theseus. One can neither compare nor contrast H.D.s Helen in Egypt with these. They are works in prose.

Her poem is not an epic; it borrows nothing from the essay or the novel; yet like the other two books, it stands alone. It is a rarity. In twentieth-century poetry, book-length poems of the first order are also rare, and H.D.s Helen in Egypt is among them. The classic spirit that inspires and sustains a poem of this length is almost lost: Helen in Egypt is a sign of its recovery. H ORACE G REGORY

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Helen in Egypt: Poetry»

Look at similar books to Helen in Egypt: Poetry. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Helen in Egypt: Poetry and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.