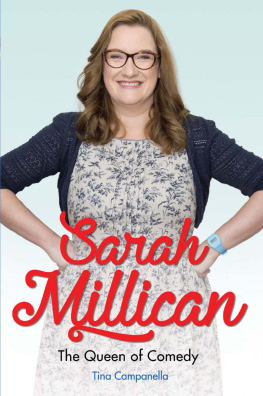

Tina Campanella is an award-winning former tabloid and magazine journalist. You can tweet her at @littlebell1982

The Early Years

I dont think a lot of the girls I was at school with would have thought for a second that I would be doing this for a living. I see it as a regeneration you know, like in Doctor Who I am a version of that person, but its a totally different version.

S arah Millican has come a very long way since she first decided to try her hand at stand-up comedy, aged 29. While other comics spend decades performing to small crowds in pubs and clubs, it has taken Sarah just eight whirlwind years to be crowned Britains new first lady of funnies.

Sarahs brand of comedy could easily be described as defiant. The Geordie comic has certainly had to fight her way through life elbows out in order to rise to the top of the UKs crowded list of comedy talent.

But it was her challenging early years that first put her on the path to becoming the queen of filthy humour that she is today. Instead of accepting her lot, she channelled even her toughest breaks into a special brand of Millican fuel which would quickly ignite her stellar career. And having a tough, caring family was central to her ability to see the humour in the negative.

Not long after her parents, Philip and Valerie, got married, they found themselves sitting on a bus, behind a little girl who was excitedly chattering away non-stop. It was an endearing sight, and one that prompted Philip to say: I want one of those

And thats exactly what they eventually got a little chatterbox who they named Sarah. The couple already had a small but perfectly formed family when Valerie fell pregnant with their second child. Their eldest, Victoria, was six when baby Sarah was brought back to the Millican family home in South Shields, on the mouth of the River Tyne, east of Newcastle.

It was May 1975, the same year that saw the birth of American comedian Chelsea Handler, comedy actor Zach Braff and presenting duo Declan Donnelly and Ant McPartlin.

It was also the same year that Charlie Chaplin was knighted by the Queen, the same year that the comedy classic Monty Python and the Holy Grail was released, and the first year that unemployment exceeded 1,000,000 in the UK.

Fellow comedians Eric Idle and Steve Furst also hail from the area that Sarah called home a pretty coastal town that experienced a boom in the 19th century because of its two main industries shipbuilding and coalmining.

But the last shipbuilder, John Redhead and Sons, closed in 1984, while the last coal pit, Westoe Colliery, stopped mining in 1993 nearly 10 years after the miners strike devastated the north east.

Sarah was a small child during that strike, and was heavily affected by the turbulent times. Her father was an electrical engineer for one of the areas many pits, and had already seen strike action before Sarah was born.

Philip was a union branch secretary during the 1972 industrial action a role that taught him a lot about staring down bullies and coming through tough times. And he went on to instil these values in his daughter, Sarah.

The miners strike of 198485 was an even harsher time in British history a period that has been immortalised in the film and the theatre hit Billy Elliot, in the BAFTA-nominated film Brassed Off and in countless books. Tens of thousands of miners went on strike to take a stand against poor pay conditions and the threat of numerous pit closures, under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. A staggering 20,000 jobs were lost as Thatcher took on the unions and it was a period of extreme hardship for the dedicated workers and their families.

Philip was one of those who went out on strike with his fellow miners and it inevitably resulted in tough times for Sarahs family.

During the year-long strike the family lived on 2 a week, but luckily Philip had talked the local shops into giving the miners bread and other foods past their sell-by date so they could feed their families.

Even then Sarah could see the funny side of the situation. Wed get end-of-day stuff, pies and cream cakes and bashed tins, that sort of thing, she has since explained. And then I remember one of the higher-end supermarkets decided they wanted to help out and they gave us 13 trays of avocados, and all of the miners went, I dont know what to do with an avocado. Wed literally never seen one before.

But even with the handouts their finances were stretched to breaking point, and Sarahs uncle would spend hours on the beach collecting driftwood for fuel.

Sarah and Victoria had no money for the bus to school and back. Instead they walked everywhere in tight shoes because the family couldnt afford new ones.

She remembers getting huge blisters on her poor feet, which bled painfully. Sarah suffered in silence, even when her feet were hurting. I didnt say anything because I knew we hadnt any money for new ones, Sarah told the Sunday Times in an interview. But then Mam went to social services and they said to her: Hasnt she got wellies? So I ended up wearing wellies all summer.

The strike marked the end of lunchtime trips home, as there simply wasnt enough food for the family to have three meals a day. Instead the two sisters ate school dinners for the first time.

We got free school dinners for a year and the dinner ladies used to give us extra helpings because they knew that was our meal for the day, she recalled in an interview with the Observer in 2011. We didnt really know what was going on except that there wasnt much money to spare. My sister still cant look at spaghetti hoops because for ages that was all we had.

As with all her tales of woe, this recollection is almost Shakespearean in its comedy. Millicans formidable talent lies in her ability to dig deep into her past for almost tragic events that will make her audience howl with laughter. Its a coping mechanism that has helped her get through tough times on countless occasions. It gives her very human brand of comedy a universal appeal.

I think you have to go through things like that to learn the value of money and to know you can actually survive on very little, she says.

Through her comedy, Sarah tries to convey a very profound message: weve all been through tough times, but there comes a certain point when we can laugh about the sad things that have happened to us. She takes those times and reminds us of them with style.

Sarahs mother, Valerie, was disabled and used a wheelchair. Shed had polio as a child, leaving her weak and in pain, but also with a dark sense of humour something she passed on to both her daughters. In fact, Sarahs sister Victoria was herself a funny and feisty child, who now says that the only difference between Sarah and the rest of her family is that Sarah gets paid for being funny.

Sarah loved her childhood, and despite it certainly being tough, insists that she never felt it was a tortured existence. Valerie was the perfect stay-at-home mum and Sarah fondly remembers coming home from school every dinnertime to find soup on the stove and her slippers warming on the pipes round the boiler. She was a protective parent, who wouldnt let her children eat space dust, or fizz-wizz, the popping candy that was so popular in the eighties because she thought it was drugs.

At home, Sarah showed her performance skills from an early age, often tap-dancing and performing poetry for her family, who were unfailingly encouraging. But she was also a shy child and admits she was very introverted. When she performed those poetry recitals they were more often than not from behind the lounge curtains. I guess I wanted to be heard and not seen, she has since joked.