Published with the support of a Carol Lavin Bernick Faculty Grant from Tulane University.

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2020 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typeface: Whitman

Printer and binder: Sheridan Books

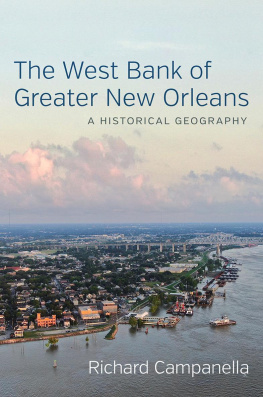

Title page image: Spring storm over Algiers Point, 2018. Photo by Richard Campanella.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

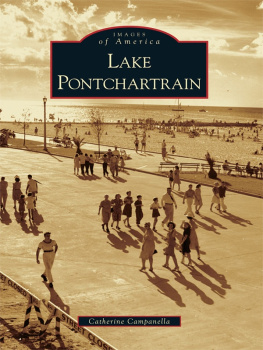

Names: Campanella, Richard, author.

Title: The West Bank of greater New Orleans : a historical geography / Richard Campanella.

Description: Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, 2020. | Published with the support of a Carol Lavin Bernick Faculty Grant from Tulane UniversityT.p. verso.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019044180 (print) | LCCN 2019044181 (ebook) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7297-1 (Cloth) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7366-4 (pdf) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7367-1 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: West Bank (New Orleans, La.)History. | New Orleans (La.)Social conditions. | NeighborhoodsLouisianaNew Orleans.

Classification: LCC F379.N56 W473 2020 (print) | LCC F379.N56 (ebook) | DDC 976.3/35dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019044180

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019044181

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Preface

French explorers called it the left bank, because it was gauche as they ascended the Mississippi. Mariners later called it the right bank, and still domore properly the right descending bank. New Orleanians in the 1800s also called it the right bank, as Parisians do of the Seine, else across the river, over the river, or opposite the city. Not until the 1900s did the vernacular converge on West Side and West Bank, the latter finally prevailing. Federal highway signs fused the words into Westbank so as not to imply a cardinal directionfor, as New Orleanians love to point out, the West Bank lies east of downtown, beneath the rising sun.

The West Bank has been a vital part of greater New Orleans since the citys inception. It has been the Kansas, the Birmingham, the Norfolk, Atlanta, Pullman, and Fort Worth of the metropolisthat is, its breadbasket, foundry, shipbuilder, railroad terminal, train manufacturer, and livestock hub. At one time it was the Gulf Souths St. Louis, in that it had a diversified industrial sector as well as a riverine, mercantilist, and agricultural economy. It served as a jumping-off point to the western frontier, and a Cannery Row for the great thalassic littoral to the south. Yet it also has substantial populations of deep-rooted locals, folks who speak with New Orleans accents, who practice old cultural traits with a minimum of pomp and self-awareness, and who, in some cases, retain family ownership of lands held since antebellum times. The West Bank makes up 30 percent of the metro population, and a commensurate amount of its urbanized footprint. It is, in short, integral to greater New Orleans in every way.

Yet the story of the West Bank has never been told holistically, on its own terms. Most books about New Orleansand there are thousandstreat it as a sideshow or an afterthought, if at all. The limited literature on the West Bank has been at the community level, and published only locally. Various dissertations and government reports have been written on certain West Bank topics. But a full-length, in-depth book about the whole subregion? Youll find plenty about that other West Bank, in the eastern Mediterranean, but none about the one on the lower Mississippi.

This book positions the West Bank front and center, viewing it as a genuine subregion unto itself, with more holding it together as a social and economic space than dividing it by various jurisdictions. It understands West Bankers to have had agency in their own place-making, and challenges the notion that their story is subsidiary to a more important narrative across the river.

The West Bank of Greater New Orleans is not a traditional history of mayoral administrations and prominent political figures such as Martin Behrman and John Alario. Nor is it a cultural history, paying homage to beloved natives like Mel Ott and Frankie Ford, or notable restaurants such as Moscas. (I am fascinated by the regularity with which East Bankers mention Moscas whenever the West Bank comes up in conversation.) Rather, it is a historical geographythat is, a spatial explanation of how the West Banks landscape formed: its terrain, environment, peoples, land use, jurisdictions, waterways, industries, infrastructure, systems, neighborhoods, and settlement patterns, past and present. It explores the players, power structures, and decisions behind those landscape transformations, and their contexts, contingencies, and consequences. The West Bank of Greater New Orleans explains how the map of this subregion came into shape, and how this place came to be.

I did not employ fixed boundaries of what was inside or outside my study area; as a geographer, I tend to resist such artificial lines. I instead used a core/periphery approach, in which the emphasis is on the Algiers-Gretna-Harvey-Marrero-Westwego core of the urbanized West Bank, but not to the exclusion of important places on the periphery, such as Belle Chasse, Avondale and Waggaman, the Nine Mile Point and English Turn promontories, Lafitte, and even Grand Isle. There are times when the regionality of the West Bank becomes one and the same with the Barataria Basin, or extends out to the German and Acadian coasts, even to Texas. If the evidence took me to the periphery, I went therebut never to the point of losing sight of the core.

To avoid anachronism, I originally intended to use language contemporary to the eraLeft Bank in the early 1700s, Right Bank for the 1800s, West Bank for the 1900s, and so on. But it proved unwieldy, so I decided to use West Bank throughout, except in quoted material. Contrary to the style sheets of some local publishers, I capitalize both West Bank and East Bank as proper nouns, treating them as genuine subregions.

I came to this topic after nearly twenty-five years studying the geography of New Orleans, having authored ten books and over two hundred articles with mostly an East Bank focus. In June 2017 I received an out-of-the-blue email from Stewart Farnet, an architect, former board member of the Harvey Canal Limited Partnership, and descendant of the Destrehan and Harvey families, who asked if I might be interested in writing a history of his illustrious ancestors.

Meeting with Stewart and his son Clay in an uptown coffee shop, I explained that while I was probably not the right person to scribe a genealogy, I was well suited to write about place and the people who made itin other words, a geography. Perhaps I could research the Destrehan land that became Gretna and the Harvey Canal? Or a history of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, which the Harvey Canal became? I soon came to realize that neither story could be told without also telling all the antecedent and adjacent storiesand so perhaps the book ought to be about the entire West Bank. Stewart agreed heartily.