The Rise and Fall of the Spanish Empire

Also by William S. Maltby

THE REIGN OF CHARLES V

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE

SPANISH EMPIRE

William S. Maltby

William S. Maltby 2009

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission.

No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS.

Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published 2009 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS.

Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martins Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world.

Palgrave and Macmillan are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.

ISBN-13: 9781403917911 hardback

ISBN-10: 1403917914 hardback

ISBN-13: 9781403917928 paperback

ISBN-10: 1403917922 paperback

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09

Printed and bound in China

For Nancy

CONTENTS

NOTES ON SPELLING AND CURRENCY

Common English equivalents of place names have been used wherever possible (e.g., Genoa, Seville). Where there are no English equivalents, the correct spelling and accents are used. Common English equivalents are also used for kings and popes (e.g., Charles, Ferdinand and Isabella, Alexander) unless there is a possibility of confusion as in the case of Joa of Portugal, Juan II of Aragon, and so on, all of whom could be called John. Other personal names receive the accents and spelling appropriate to their own country unless, as in the case of explorers like Columbus and Magellan, a common English equivalent exists. It would be pedantic to call them Cristoforo Colombo or Ferna Magalhes. For the same reason, the English equivalents of foreign titles (Duke, Count, Marquis, etc.) are used wherever possible.

Most of the figures provided in the text are quoted in monies of account. The smallest Spanish money of account was the maraved. For most of the sixteenth century, 375 maraveds equaled one ducat. The escudo that appears as a money of account after 1590 was the escudo de diez reales. It was based on silver rather than gold and had a value equivalent to 340 maraveds. The florin was the primary money of account in the Netherlands. It was generally equivalent to 0.4 escudos. Ten florins or four escudos equaled 1sterling.

The Spanish coins to which these monies corresponded were the escudo and the real. The escudo was a gold coin, 22 carats fine, of 3.38 grams. When introduced in 1535 it was worth 350 maraveds, but inflation increased its nominal value to 400 in 1566 and 440 in 1609. The real was a silver coin of the same weight, although some were minted at 3.43 grams. It was valued originally at 34 maraveds. Coins of 1/4, 2, 4, and 8 reales were also minted. The last were the famous reales de a ocho, or pieces of eight, a currency accepted throughout the world in the seventeenth and eighteenth century. The peso, which became the standard currency of the Spanish Empire after 1772, was minted at the same weight and quality of silver as the real de a ocho, but a portrait of the king replaced the Pillars of Hercules that had adorned Spanish coins since the reign of Charles V. The United States silver dollar and the Austrian thaler were based on the real de a ocho as well. Spain, to its credit, never devalued its gold and silver coins, most of which were minted in America. The coins issued in peninsular Spain beginning in the reign of Philip III were minted from an alloy called velln. While the value of a silver real rose to 275 maravedis by the 1620s, the reales velln issued to Spaniards were valued at only 34 maraveds.

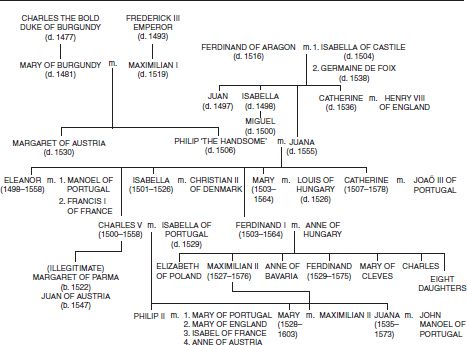

GENEALOGICAL CHARTS

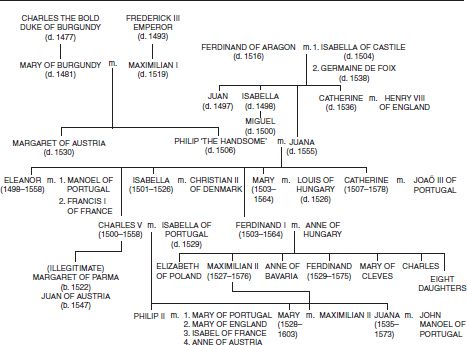

THE INHERITANCE OF CHARLES V

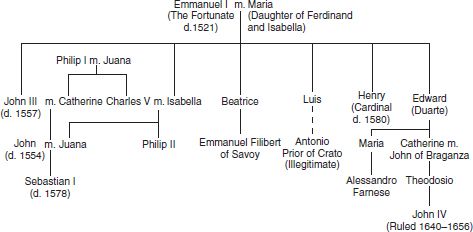

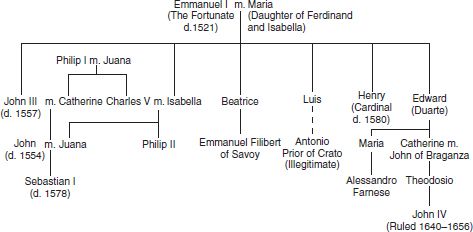

THE PORTUGUESE SUCCESSION

THE SPANISH SUCCESSION, 1700

MAPS

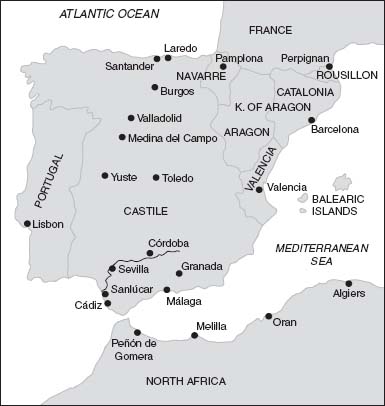

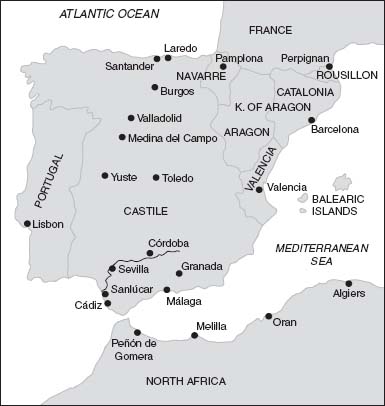

Spain

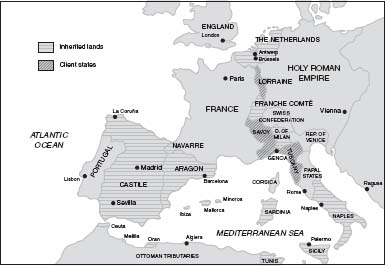

The Netherlands at the Death of Charles V

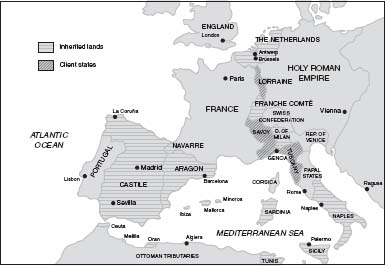

The European Empire of Philip II

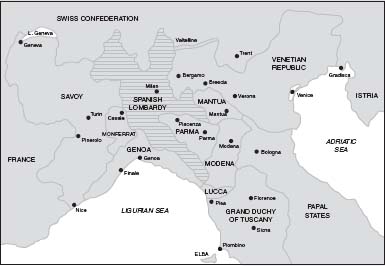

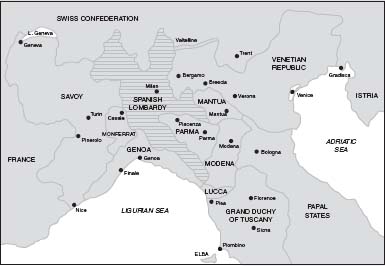

Northern Italy in the 17th Century

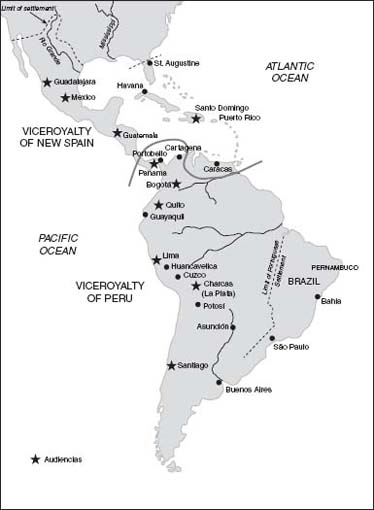

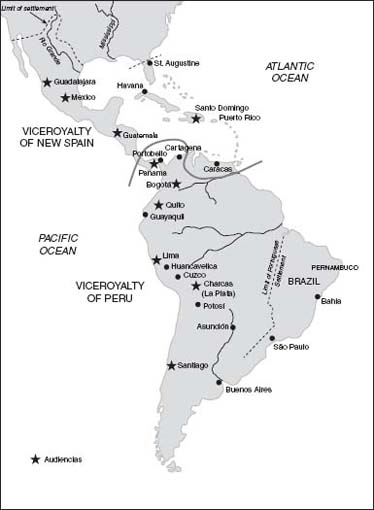

Spanish America under the Habsburgs c.1650

Spanish America under the Bourbons c.1790

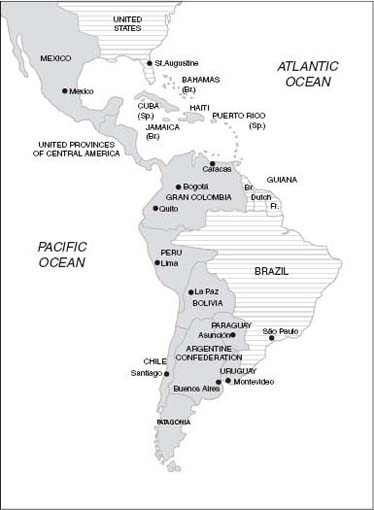

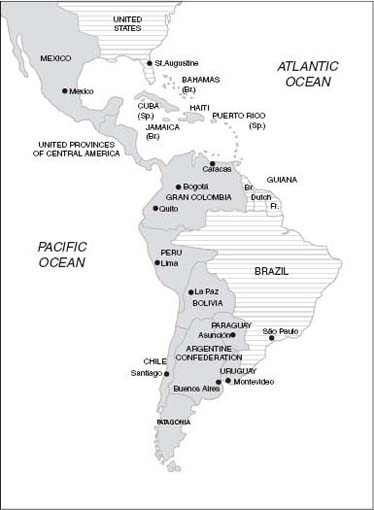

Spanish America in 1828

INTRODUCTION

European colonialism, the centuries-long rule of European nations over societies thousands of miles from their shores, has few if any parallels in the history of humankind. No other civilization with the possible exception of Han Dynasty China attempted such a thing, and the Chinese experiment had few long lasting consequences. In contrast, European colonialism shaped the contours of the modern world by helping to foster global integration or globalization, a movement which until the mid-twentieth century proceeded largely on Europes terms.