Published in 2014 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2014 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2014 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager, Core Reference Group

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Kenneth Pletcher, Senior Editor, Geography

Rosen Educational Services

Shalini Saxena: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Amy Feinberg: Photo Researcher

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Kenneth Pletcher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

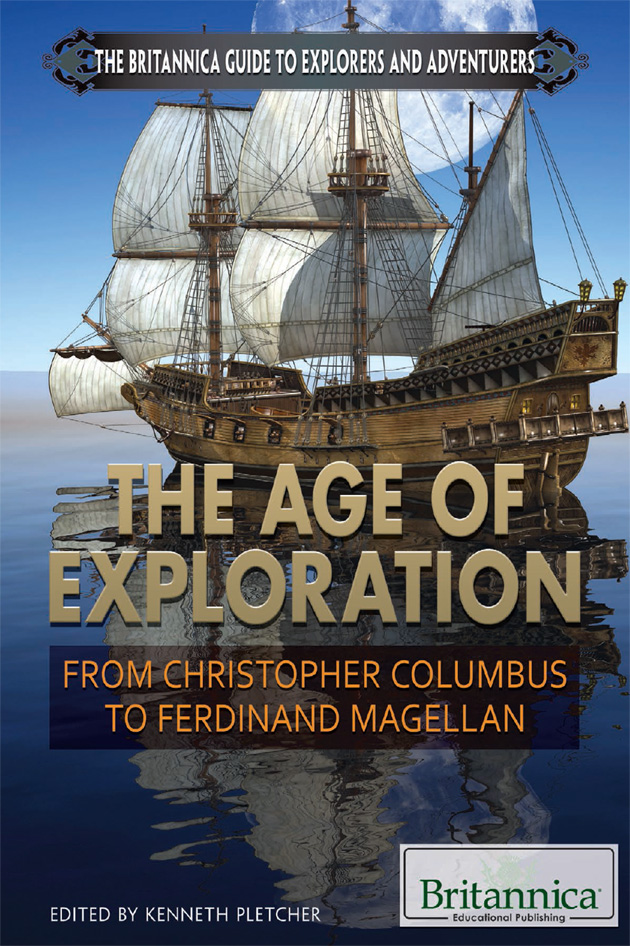

The age of exploration: from Christopher Columbus to Ferdinand Magellan/edited by Kenneth Pletcher.1st ed.

p. cm.(The Britannica guide to explorers and adventurers)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62275-023-8 (eBook)

1. Discoveries in geography. 2. Explorers. I. Pletcher, Kenneth.

G200.A37 2013

910.92'2dc23

2012038340

On the cover: A ship whose design is typical of those employed during the Age of Exploration. iurii/Shutterstock.com

Cover, p. iii (ornamental graphic) istockphoto.com/Angelgild; interior pages (scroll) istockphoto.com/U.P. Images, (background texture) istockphoto.com/Peter Zelei

T he century and a half between 1400 and 1550 was a remarkable time in world history. In Asia, the continents two great civilizations, China and India, were developing highly sophisticated culturesthe Chinese under the Ming dynasty (13681644) and India under a series of smaller polities that eventually became the Mughal empire (early 16thmid-18th century). In both lands, especially in China, much of the external focus during that time was on preventing more of the incursions from Mongols that had so dominated previous centuries. Indeed, perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Ming is Chinas Great Wall, the remaining sections of which are testament to the enormous resources the Chinese expended maintaining and expanding that barrier and symbolic of their efforts to keep outsiders at bay.

Meanwhile, throughout Europe, nations centred on monarchies were beginning to emerge from the manor-based decentralized feudal society that had been in place for centuries. The process progressed to such a degree that by the beginning of the 16th century, centralized authority, within the frontiers of the nation-state, covered much of the continentthe first time it had been so since the Roman Empire. The economy of Europe was also being transformed from one largely of labour services provided to lords by the serf class to more of a money economy in which peasants, artisans, and merchants played an increasing role. This was made possible in large part by the terrible plague epidemics of the second half of the 14th century, which had so depleted the continents population that they had contributed significantly to the ruin of the landowners.

The 15th and 16th centuries also witnessed the great cultural and intellectual flowering in Europe known as the Renaissance that produced such renowned individuals as Leonardo da Vinci, Niccol Machiavelli, and William Shakespeare, as well as the remarkable innovation of printing with movable type that greatly facilitated the dissemination of information. While much of Asia may have been focused more inward than outward during that time, Europe was looking to push beyond its boundaries, drawn by the wonders and riches of the East that it had learned of from such travelers as Marco Polo. Access to the East by land, however, had become difficult by 1400. The vast empire of the Mongols, which had once stretched across Eurasia, was much diminished, and European merchants could no longer rely on the safety of such land routes as the ancient Silk Road. In addition, the Ottoman Turks, who were hostile to Christian Europeans, were growing in power in the Middle East, and they effectively blocked the outlets to the Mediterranean Sea of Europes traditional sea routes from Asia.

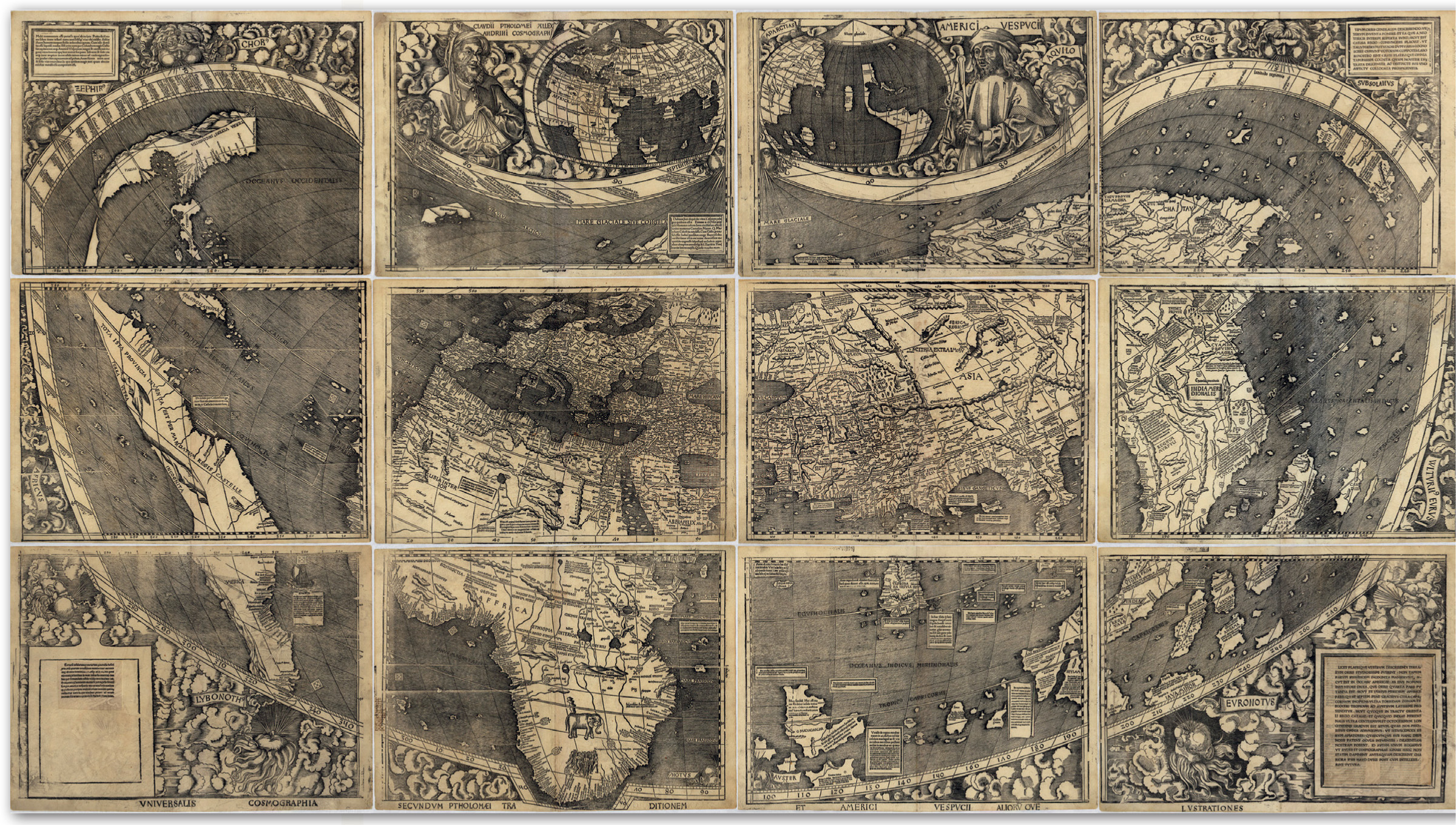

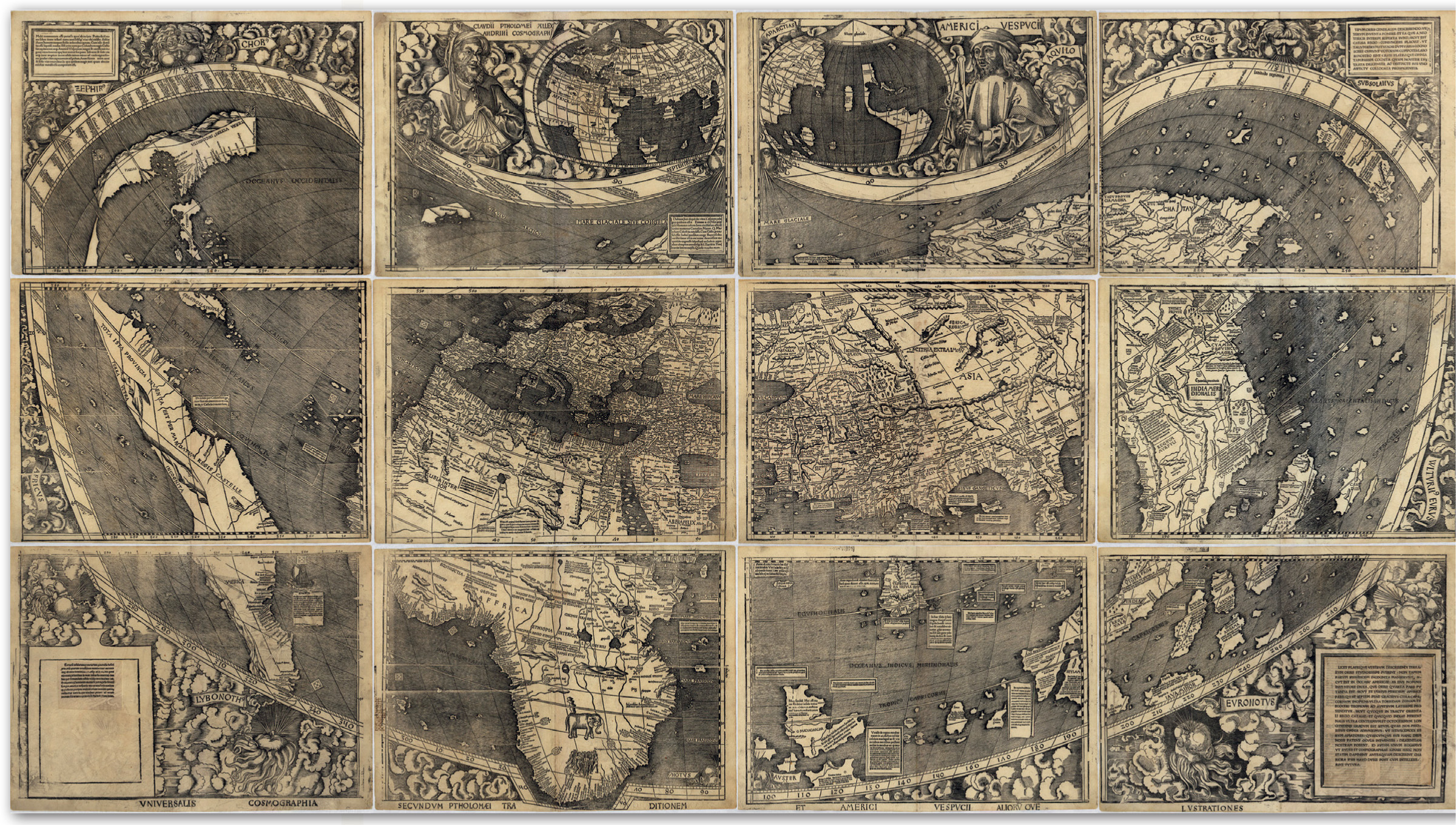

World map by Martin Waldseemller, 1507, in which the name America first appears in reference to the New World. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division

Those circumstances, along with the growing desire of the emerging European states for trade and adventure, became great incentives for those in the West to seek new sea routes to Asia. The first great overseas voyages of the 15th century, however, did not originate in the West but were those of the renowned Chinese admiral Zheng He, sent by the Ming on seven expeditions between 1405 and 1433. That would prove to be the last such venture mounted by the East. In contrast, in the 100 years between the mid-15th and the mid-16th century, a seemingly endless stream of explorers and adventurers struck out from European shores.

The first of these remarkable European enterprises was the search for a southern sea route to China, initiated by Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal, who sent out a series of expeditions to explore the Atlantic coast of Africa. By the time of his death, in 1460, his captains had reached as far south as what is now Sierra Leone. The Portuguese continued pushing farther south and east along the coast, until Bartolomeu Dias (or Diaz) rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 and proved the existence of an open sea passage between the Atlantic and Indian oceans. By the end of the century, Vasco da Gama had led the voyage around the Cape that reached the west coast of India and provided the final western link in the route to China.

In 1500 yet another Portuguese fleet set out for India, this one under the command of Pedro Alvarez Cabral. He had been advised to sail southwestward to avoid the calm waters off the coast of Guinea, but he sailed so far to the west that he reached Brazil. Initial enthusiasm for this discovery soon waned, however, as Portugal maintained its eastward focus. Trading entrepts were quickly established along the African coast, at strategic entrances to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, and at locations such as Goa along the coast of the Indian subcontinent. By 1512 Portugal had established a base on the Strait of Malaccaand thus could control access to the South China Seaand had reached the Spice Islands (Moluccas) and the island of Java (both now parts of Indonesia).