T he saga of the liner Lusitania has intrigued me for many years in the same way that others have been fascinated by the drama of the maiden voyage of Titanic. In the early 1970s a former Director of Cunard told me that the liners history and the reasons behind her sinking had never been adequately told and that it was a far bigger and much more important story than that of her contemporary. My interest in the liner was rekindled by Dr Robert Ballards exploration of her wreck with submarines and by a conversation my wife Pamela and I had when we were travelling on QE2 with a well-known maritime historian who was lecturing on Titanic. He remarked on the number of books which had recently been published on that ill-fated liner, which had found a ready sale although some of them were frankly mediocre. His conversation spurred me to write this book which I have based on detailed research on both sides of the Atlantic. The saga which unfolded in front of me was even more intriguing than I had assumed. Over the years it has become encrusted with myths, some of which can be traced back to German propaganda in the aftermath of the sinking, and others which have their origin in the understandable desire of the British Admiralty to let sleeping dogs lie. My intention has been to examine and rebut the many myths of Lusitania.

The passing of the years has carried away not only almost all the survivors but sadly some valuable source material. In the 1960s the late John Light carried out some forty dives on Lusitanias hull, which at one time he owned. He also built up an archive on the liner which reputedly contained about 15,000 items. Following the death of his widow a few years ago, the present location of these documents is unknown. Although Lights conclusions were often debatable, the apparent disappearance of his archive is a serious loss to anyone writing on the liner. The correspondence between Alfred Booth, the then Chairman of Cunard, and his cousin George, the Managing Director of the family firm of Booth & Co and a major figure in the City of London, together with George Booths papers and his unfinished autobiography, which was made available to at least one earlier writer, also seem to have disappeared. The admirable Cunard Archives at Liverpool University include remarkably few papers on the line in the First World War. A file marked Chairmans Correspondence with the Admiralty 191419 contains a mere handful of papers, none of them relevant to Lusitania.

I owe a very considerable debt to Captain David Garstin RN, naval engineer by profession and enthusiastic naval historian, for the quite invaluable help he has given me particularly in the technical aspects of the liners design and in establishing the reasons why she sank in only eighteen minutes. He has corrected many of my errors and I have incorporated almost all of the suggestions he made to me after he read my various drafts. Last but not least, he warned me of the dangers of hindsight in making judgments about those who were involved in the events which preceded and followed the sinking of Lusitania, both aboard the liner and ashore. I would also thank Lieutenant-Commander Paul Satow RN for his advice about navigation and Rear-Admiral Geoffrey Mitchell RN, a former Director of Naval Operations and Trade, for reading the chapters that discuss what degree of responsibility the Admiralty bore for the tragedy.

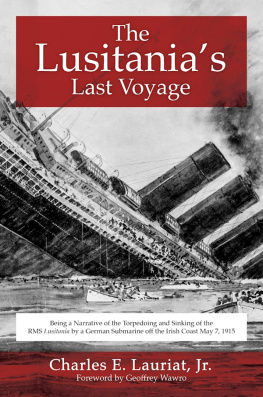

Lord Bridgeman, the grandson of a distinguished First Lord of the Admiralty, kindly delved into the House of Lords Library and provided me with copies of contemporary issues of The Times and The Morning Post, which I have found to be high quality source material as are the books written by the Lusitania survivors, Oliver Bernard and Charles Lauriat. The late Philip Bates, a former Managing Director of Cunard, gave me the benefit of his considerable knowledge of the line and of the Liverpool shipping world in general. David Inglefield and Imelda Lutyens kindly gave me access to the papers of their grandfather, Admiral Sir Frederick Inglefield, Senior Naval Assessor at the Mersey Inquiry into the loss of Lusitania. Audrey Lawson Johnson, who was rescued from the disaster when she was only three months old, lent me a most useful collection of newspaper cuttings and documents and told me of her memories of her parents, Warren and Amy Pearl, who also survived the sinking. Sadly, I was unable to meet the intrepid Alice Lines Drury, the nanny who had saved her, who died, aged 100, a few months after my meeting with Mrs Lawson Johnston. Tom Johnson and his staff at the Rancho Mirage Public Library went out of their way to obtain books as source material from the admirable Interlibrary Loan System. The distinguished marine artist, Harley Crossley, painted the picture for the dust jacket. Alec Herzer (Venture Graphics) compiled the chart of the the waters off the South Coast of Ireland, which uses the latest data.

I express my gratitude to the staff of the Public Record Office, Kew, the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich and the Cunard Archives and also to Carole Leadenham, Assistant Archivist at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Piers Brendon, Keeper of the Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge and his archivist, Alan Kucia, Peter Simpkins and his colleagues at the Imperial War Museum, Professor Michael Moss and Moira Rankin, University of Glasgow, and Rachel Mulhearn, Merseyside Maritime Museum, all of whom gave me full measure of assistance. My son James, in the interval between receiving his MBA and his appointment to run an executive relocation company, undertook some research for me at the Imperial War Museum and in the Booth family papers at London University. Judy Collingwood carried out additional research for me into the Admiralty files at the PRO.

My thanks are also due to all those in Great Britain, the United States, Belgium, Canada, Germany and Ireland who helped me in my research, particularly Paul Banfield (Queens University, Kingston, Ontario), Captain Edward Beach USN, Count Bertil Bernadotte, Tobias Graf Von Bernstorff, Lady Bridgeman and her staff at the Bridgeman Art Gallery, David K Brown, Wim Coumans and Luc De Munck (Belgian Red Cross), Richard Crissman, Chris Doncaster, who alerted me to the heroic efforts of the Manx fishing boat Wanderer in saving lives after Lusitania was sunk, William H Garzke, Graham C Greene, Oliver Greene, Dr Alan Jamieson, Sir Ludovic Kennedy, Arnold Kludas, David Mackay, Professor Walter McDougall (University of Pennsylvania), Dr Joe A Martin, Roy Martin, John Maxwell (Hill Dickinson), Ranald and Patricia Noel-Paton, Belinda Norman-Butler, Sir Thomas Pilkington and Captain Graeme Cubbin (Harrison Line), Maighread Rutledge (Cobh Heritage Centre), Lord Rees-Mogg, Max Roberts, who gave me details about the life of Captain Turner, General Michael Rogers USAF, Arthur Sandiford, Rupert Graf Strachwitz, Major-General Julian Thompson, Steve Torrington (Library Editor, Associated Newspapers) and Captain Ronald Warwick.

I acknowledge the authors and publishers of the following works from which I have quoted:

Thomas Bailey & Paul Ryan, The Lusitania Disaster (Free Press); Correlli Barnett, Engage The Enemy More Closely (W W Norton); Oliver Bernard, Cock Sparrow (Jonathan Cape); W S Chalmers, Full Cycle (Hodder & Stoughton); Kendrick Clements, Woodrow WilsonWorld Statesman (Twayne); Allan Crothall, Wealth From The Sea (Starr Line); Reinhard Dorries, Imperial Challenge: Ambassador Count Bernstorff and German-American Relations 19081917 (University of North Carolina); Niall Ferguson, The Pity Of War (Allen Lane); James Gerard, My Four Years in Germany (Hodder & Stoughton); Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill